MetaScan 4 – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

Policy Challenges and Opportunities for Canada

On this page

Economic sea change

Preparing for an increasing number of virtual workers

Preparing for the rise of digital trade

Anticipating a world where traditional policy instruments are less effective

Anticipating the declining demand for oil

Preparing for the (eventual) transition to a low-carbon economy

Preparing for the rise of Asian institutions

Redesigning security policy around next generation threats

Rethinking strategies for failed and fragile states

Adapting to adaptive authoritarianism

Learning from and adapting to new Asian policy models

Welcoming Asia’s growing confidence and expanding influence

Notes

A policy challenge or opportunity is an issue that current policies or institutions may not be ready or able to address. Identifying, analyzing, debating and clarifying challenges and opportunities helps develop robust policy and strategies. The rapid changes that may occur in Asia over the next 10-15 years will present Canada with a range of challenges and opportunities. This section highlights those that may be particularly surprising and unexpected.

Economic sea change

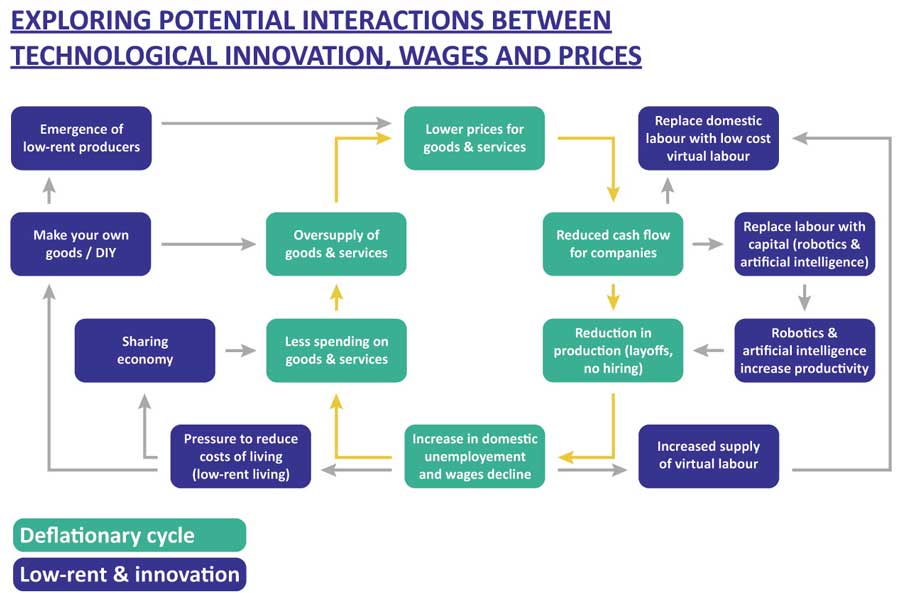

Asia’s rapid embrace of new technologies and business models could accelerate the global transition to a digital economy and bring on an extended period of economic and social disruption for Canada. Recent technological developments combined with Asia’s investments in modern, fast, cheap and smart digital infrastructure, mean that much of Asia’s population is poised to enter the global digital economy. This will likely increase the pace of adoption and innovation of emerging features of the digital economy such as job unbundling, virtual work, and the collaborative economy. Combined with rapid advances in automation and 3D printing these changes could lead to significant disruptions in prices, employment, and business models around the world. Complicating this issue is the potentially rapid pace of these changes over the next 10–15 years and the mutually reinforcing nature of these challenges (where declining wages and employment could force consumers and businesses to seek ever more cost effective goods and services — see Figure 10). From an economic perspective, surging productivity and falling prices FIGURE 10 should lead to a net benefit for society in the long run as business models and workers adjust to this new reality. However, the path to achieve this brighter future may be long and recessionary with unequal distribution of benefits. This could place significant pressures on economic development, trade, taxation and social policies in Canada.

Figure 10 – Exploring the potential interactions between technological innovation, wages and prices

This figure explores the potential interactions between technological innovation, wages and prices. This image is a system map consisting of green and purple text boxes of various elements which show the relationships among them. The legend at the bottom of the image assigns the green text boxes to deflationary cycle, while the purple boxes represent low-profit & innovation. The system map starts in the centre with the deflationary cycle and moves in a clockwise direction with the following 6 elements: 1) lower prices for goods & services; 2) reduced cash flow for companies; 3) reduction in production (layoffs, no hiring); 4) increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline; 5) less spending on goods and services; and 6) oversupply of good & services. All of these elements are linked in a clockwise direction with a yellow arrow. The outer part of the system map is made up with the following 8 low-profit and innovation elements: 1) emergence of low-profit producers; 2) replace domestic labour with low cost virtual labour; 3) replace labour with capital (robotics & artificial intelligence); 4) robotics & artificial intelligence increase productivity; 5) increased supply of virtual labour; 6) pressure to reduce costs of living (low-profit living); 6) sharing economy; 7) make your own goods/DIY; and 8) emergence of low-profit producers. Increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline links to pressure to reduce costs of living (low-profit living) which links to sharing economy, make your own goods/DIY and emergence of low-profit producers links to lower prices for goods & services. Increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline also links to increased supply of virtual labour which links to replace domestic labour with low cost virtual labour. Replace labour with capital links to robotics and artificial intelligence links to reduction in production. Reduced cash flow for companies links to replace domestic labour with low cost virtual work and replace labour with capital.

Preparing for an increasing number of virtual workers

Canadian workers may face a potential race to the bottom as the market for services moves to global online contracting platforms. Virtual work platforms are growing rapidly as sources of employment and labour. This can bring several benefits, providing Canadians with new flexible work and entrepreneurship opportunities, while granting Canadian businesses, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs), enhanced productivity and access to new markets.117However, virtual work also brings Canadians into more direct competition with similarly-skilled people around the world, many of whom live in areas with lower incomes and costs and may therefore be willing to perform tasks of the same quality for significantly less pay. Moreover, virtual work platforms typically lack the protections of a social safety net, health and safety standards, or clarity around intellectual property.118 In this context, the potential advent of hundreds of millions of digitally connected, skilled, motivated and generally lower-wage virtual workers from Asia could drive downward pressure on wages, social safety nets and working conditions in higher wage countries such as Canada. Assisted by improvements in telepresence, automated translation, and remotely controlled robotics, competition from virtual workers could impact a wide range of previously unaffected jobs in both virtual and physical domains. Finally, this increased competition will likely come at the same time as a growing number of jobs are being further automated due to advances in robotics, AI, and other labour-saving technologies (see box).

The rise of virtual work and increased pressure from low-cost labour could require a significant rethink of existing social and labour market policies, and may stem demand for immigration. To prevent a race to the bottom, international cooperation around tax collection and social protections, work permits and qualifications may be necessary. Online platforms could become important partners in regulating their digital marketplaces. New approaches to government-funded education and entrepreneurship supports may be needed to help Canadians be successful in a more global and competitive digital economy.

Supporting videos

- The World Bank: “ICTs & Jobs: Connecting People to Work”(link is external)(3:56 mins)

- IPsoft: “Amelia: The First Cognitive Agent Who Understands Like a Human”(link is external)(1:31 mins)

- Komatsu: “Autonomous Haulage System”(link is external) (2:56 mins)

- Rethink Robotics: “Redefining Automation with Baxter”(link is external)(1:37 mins)

Preparing for the rise of digital trade

As Asia and the world increasingly shifts towards digital trade, traditional trade policy approaches may no longer be relevant or effective. A whole new world of trade in digital goods and services is emerging and growing fast. McKinsey estimates that global online traffic across borders could increase eight-fold by 2025,119 with Asia leading the way.120The potential impact of this digitization of trade is only beginning to emerge. For large corporations,digital trade increases efficiency, lowers operating costs, and facilitates tax optimization strategies. But perhaps the most dramatic change is for individual entrepreneurs and small- and medium size firms, for whom digital trade can unlock huge new global markets. “Internet platforms are empowering these ‘micro-multinationals,’ enabling them to find customers, suppliers, funding, and talent around the world at lower cost. Digital platforms can cut the cost of exporting by 83% as compared with traditional export channels.”121 Digital trade in goods and services is likely to expand and co-evolve with the development of artificial intelligence, data analytics, sensors and the Internet of Things, and international digital services are likely to penetrate deeply into our lives and homes. In summary, the world is entering an era of intense competition and enormous opportunity. For governments the challenge is how to monitor, regulate and enforce standards in the emerging digital value chain in areas like finance, labour, health and safety. Traditional trade protections and trade liberalization agreements may become less relevant as a greater percentage of global trade is able to bypass state monitoring and control. Investment controls, taxation, regulation, anti-trust and privacy protections may also be affected. It is possible that de facto trade liberalization is already underway in the digital economy. Canada has been successful in building ports and eliminating tariffs to prosper in the current trade regime, but may need to give more thought to preparing for the emerging era of digital trade.122

Anticipating a world where traditional policy instruments are less effective

As we enter the digital era, physical borders and even the nation state will likely matter less. National borders and the related economic, tax, health, safety and labour policies will be difficult to enforce using traditional instruments in the emerging digital world where many “workarounds” are possible. For example, imagine the challenges of enforcing a minimum wage policy. Digital work platforms allow workers and firms to work anywhere. In a virtual project with workers in several countries, whose rules apply? What is the enforcement mechanism? Solving this kind of problem may require international cooperation as well as new partnerships with global corporations, not-for profit organizations and civil society. For instance, governments could collectively set norms that other actors monitor and enforce. Virtual work platforms could apply international compensation standards including wage floors for some tasks,coordinate online training, run health and social insurance programs and collect taxes. Tracking environmental performance and combatting cybercrime are additional challenges increasingly beyond the capability of traditional nation-state approaches. Regardless of the domain, policy makers will need to explore how their instruments and policies would fare in a global digital economy.

Anticipating the declining demand for oil

Lower than expected demand for petroleum products in Asia could contribute to unexpected weakness in the global crude oil market.123 Low-cost oil producers may not curtail supply to increase prices because they will be competing to maintain their respective shares of a diminishing market, seeking to maximize the extraction of their reserves before oil is replaced as a predominant energy source. As a relatively high-cost producer, Canada may find it difficult to compete leading to a loss of tax and royalty revenues (impacting fiscal budgets) and decreased investment in the petroleum sector (impacting employment and increasing the risk of public investment in petroleum related assets). Governments may also need to ensure adequate safeguards are in place to address decommissioning and remediation of extraction sites and infrastructure if companies exit the sector due to low profit margins.

Preparing for the (eventual) transition to a low-carbon economy

Canadian goods and services, including primary energy and natural resources, may face trade restrictions or challenges based on their carbon content. As Asia’s energy mix shifts towards low carbon, governments may seek to erect barriers to protect their markets from higher carbon content imports. Alternatively, or simultaneously, they may challenge trade and non-trade measures that are seen as protecting high-carbon sectors in developed world economies. Non-trade measures could also be implemented including requirements for Canadian exporters to disclose carbon emissions/footprint information to maintain access to Asian markets. Government to government intervention may be ineffective if carbon footprints are used to inform individual or corporate purchasing decisions that discriminate between alternative suppliers throughout the value chain rather than as the basis for government implemented trade restrictive measures. Asian countries or trade blocks may see an economic or competitive advantage in promoting carbon footprinting as a means of positive discrimination for its exports or for excluding imports from economies with higher carbon footprints in their energy mix. If there is strong demand for carbon content reporting from Asia’s emerging middle class, it could become a basic requirement of doing business in Asia and potentially lead to Asian methods for calculating carbon content becoming the global standards.

Preparing for the rise of Asian institutions

There is a closing window of opportunity for Canada to influence Asia’s regional architecture before it begins redefining global norms and practices. Some Asian agreements — like the proposed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, for instance — already exclude Canada. Furthermore, the absence of a multilateral framework guiding Asia’s trade negotiations could force Canada to navigate an environment dominated by “hub-and-spoke” configurations, where bigger players like China and the U.S. set the tone and scope of collective negotiations. Without greater engagement in the region, Canada risks falling behind other middle powers. Canada has an opportunity to leverage its niche capabilities in resource management, financial services, governance, environmental protection, and supply chain resilience, to gain influence and protect its interests in Asia. Providing leadership on complex governance matters such as the establishment of rights and protections for virtual workers might afford Canada greater access to Asia’s emerging institutional architecture.

Supporting video

Redesigning security policy around next generation threats

By increasing the destructive power of individuals and non-state actors, emerging technologies may alter the nature of warfare and insecurity in Asia and beyond, forcing Canada to rethink its defensive, offensive, and deterrent strategies and policies. The breadth and scope of emerging disruptive technologies (e.g. bio-engineering, nano-technology, synthetic biology, robotics, anti-satellite and space weaponry, and digital platforms) may dramatically reduce the utility of traditional weapons platforms and defensive strategies in protecting Canadian national and economic interests. Improving cyber defence, for instance, may require building nimble capacities better able to detect breaches in digital security, attribute sources of attack, minimize damage, and mount proportional retaliatory strikes. Canada’s security partnerships may also have to better incorporate digital defence into their alliance structures and doctrines. Communicating defensive and offensive digital capabilities may further deter cyber aggression. Cyber-espionage may likewise become a growing source of tension between rival states, complicating the degree of collaboration between the U.S., China, India and other major powers that may be needed to ensure the viability, growth, and stability of the global digital economy. Beyond cyberspace, preventative self defense could incorporate the disruptive nature of next generation technologies into strategies for addressing novel and emerging threats to critical national assets. Canada may be compelled to re-examine the effectiveness of organizational structures originally designed for a pre-digital era.

Supporting videos

Rethinking strategies for failed and fragile states

Given the challenges in promoting peace and development in fragile states, new approaches may be required. The problems in fragile states are extraordinarily complex and costly. In this context development is an incremental process of ensuring security while supporting institutional and civil society development and encouraging economic activity. A recent OECD Development Assistance Committee report on fragile states (link is external)highlights the tight linkage between poverty and fragility. One of the biggest challenges to long term stability is to help the poorest people build viable economic activity amid the chaos. Inexpensive emerging technologies could be a game changer in developing local strategies to deliver energy, education, health and opening direct access to the emerging digital economy. China’s “New Silk Road” and other continental infrastructure projects may provide further opportunities to join the regional economy. The issue will be on whose terms and at what cost the fragile states agree to join. Overall, there is a need and an opportunity to use new tools and develop new strategies to work with citizens in failed and fragile states to support them in addressing overwhelming problems in more effective ways. Canada could make a useful contribution to this problem while building skills and expertise that are relevant in promoting economic development and low cost services at home.

Adapting to adaptive authoritarianism

With enhanced digital capacity to listen, analyze, and respond to public demands, highly centralized and single party governments may emerge as viable models for growth and stability. Data analytics and AI will allow states to survey popular concerns without the need to consult citizens directly and offer the potential to reduce corruption and improve transparency. Recent events have reframed internet censorship124 and monitoring(link is external)125 as tools used by democracies and authoritarian regimes alike, legitimizing the use of such strategies. Some authoritarian states may prove better prepared to capitalize on these new tools. The possibility that debate and stalemate over complex policy choices could paralyze multiparty democratic states would further highlight the dexterity of alternative models. The ideal of democracy as the most effective form of government may fade. This could lead to situations in international fora where authoritarian states are proposing more rational, far-sighted solutions than stalemated or short-sighted democracies. The perceived legitimacy and effectiveness of adaptive authoritarian regimes could cause Canada to rethink some of its strategies and partnerships.

Learning from and adapting to new Asian policy models

Innovative Asian social policy may become a leading model for others to imitate and even inspire new international standards. India’s new IP regulation strikes a balance between the demands of pharmaceutical companies and the public health needs of poorer populations.126 Similar regulation is being considered by developing countries across the globe. Norms and standards from Asia are likely to frame certain issues in a manner that may be at odds with Canadian values. While westerners today might scorn the encroachment of a “nanny state”, as Asian governments address similar policy problems with a different regard for collective versus individual interests, solutions from the East might grow more influential. Should Canadians face similar challenges to those addressed in Asia, voters may welcome new approaches to social policy previously considered unsuited to Canadian values. Canadian businesses could profit from these opportunities, by actively participating in shaping a wave of change in Asia which will eventually impact Canadian society.

Welcoming Asia’s growing confidence and expanding influence

As Asia rises, a fundamental change in how Asia views itself, and how the rest of the world views Asia, may take place. This could lead to different choices and behaviours at many levels within Asia, from where parents want their children to study in school, to choice of consumer brands to how Asia projects itself on the world stage. Asia’s expanding influence may also give Asia a new opportunity to reframe success along Asian lines, with a rediscovery and flourishing of Asian practices and cultural exports shaping global norms and values.127 Canada might see a decline or return home of Asian talent residing in Canada, while the Canadian-born may also be drawn to this new global centre in greater numbers. New definitions of sustainability, labour standards or human rights may emerge, more favourable to Asian countries and economies or more compatible with Asian tastes and values.

Supporting video

Big Think: “Kishore Mahbubani: Is the West Afraid of a Rising Asia?”(link is external)(4:09 mins)

Notes

117 The Economist. 2015. “There’s an app for that: Freelance workers available at a moment’s notice will reshape the nature of companies and the structure of careers.” January 3. http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21637355-freelance-workers-available-moments-notice-will-reshapenature-companies-and(link is external)

118 Graham, Mark. 2014. Investigating virtual production networks in sub-Saharan African and southeast Asia.”Oxford Internet Institute: The Policy and Internet Blog. November 3. http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/policy/investigating-virtual-production-networks-in-sub-saharan-africa-southeast-asia/(link is external)

Oxford Internet Institute. 2015. “Microwork and virtual production networks in sub-Saharan Africa an south-east Asia.” http://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/projects/?id=119(link is external)

119 Manyika, J., et al., 2014. Global Flows in a Digital Age. McKinsey Global Institute. April. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/globalization/global_flows_in_a_digital_age(link is external)

120 Chen Y., et al. 2015. China’s rising internet wave: wired companies. McKinsey & Company. January. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/chinas_rising_internet_wave_wired_companies(link is external)

121 Commerce 3.0 for development: The promise of the Global Empowerment Network, eBay, 2013, ebayinc.com.

122 Goldfarb, D. 2011. Canada’s trade in a digital world. Conference Board of Canada. April. http://www.conferenceboard.ca/reports/briefings/tradingdigitally/default.aspx?pf=true(link is external)

123 International Energy Agency. 2014. World Energy Outlook 2014. p. 95: “The net growth in oil demand comes entirely from non-OECD countries: for each barrel of oil eliminated from demand in OECD countries, two additional barrels of oil are consumed in the developing world. India and Nigeria are the countries with the highest rates of oil demand growth. China becomes the largest oil-consuming country in the early 2030’s, but higher efficiency and lower rates of growth in the industrial activity and in demand for mobility (as population numbers level off in the 2030’s) mean that, by 2040, oil demand growth all but comes to a halt in China.”

124 Laurie, L. 2014. “David Cameron’s internet porn filter is the start of censorship creep.” The Guardian. March 2, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jan/03/david-cameron-internet-porn-filter-censorship-creep(link is external)

125 MacAskill, E. 2013. “NSA Files: Decoded.” The Guardian. March 2, 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/interactive/2013/nov/01/snowden-nsa-files-surveillance-revelations-decoded#section/1(link is external)

126 Singh, K. 2012. “More nations adopting Indian intellectual property regulations for drug manufacturing.” The Economic Times. June 22. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-06-22/news/32368898_1_compulsory-licence-intellectual-property-shamnad-basheer(link is external)

127 Friesen, David. 2013. “Traditional Chinese Medicine: Business Blockbuster or False Fad?” CKGSB Knowledge. January 8. http://knowledge.ckgsb.edu.cn/2013/01/08/china/traditional-chinese-medicine-business-blockbuster-or-false-fad/