Geostrategic Cluster Findings – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

PDF: Geostrategic Cluster Findings – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

On this page

Introduction

Summary of Key Geostrategic Changes in Asia (Insights) and Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

Key Changes in Asia (Insights)

- Asia asserts its role as a global rule-maker

- Asia compelled to move beyond narrow definitions of security

- Asia’s urban revolution alters diplomatic relations

Policy Challenges and Opportunities for Canada

- Closing window to influence

- Maintaining flexibility in adapting to overlapping trade regimes

- Canadian military engagement in Asia

- Managing complexity in an age of converging security threats

- Addressing Asia’s regional instability with strategic engagement

- Maintaining cyber security in the new digital era

- The next oil – managing water to Canada’s strategic advantage

- Aligning multiple agendas to advance Canada’s strategic role in Asia

Note to the reader

This Geostrategic Cluster Foresight Study explores key changes in Asia and policy challenges and opportunities for Canada. The key changes are in the form of “insights”, which identify existing and emerging developments that may significantly alter the system under study. Insights help build our understanding of how an issue or system may evolve and what the consequences might be. A policy challenge or opportunity is an issue that current policies or institutions may not be ready or able to address. Identifying, analyzing, debating and clarifying challenges or opportunities help policy makers develop more robust strategies.

Part of the Horizons Foresight Method also involves the exploration of plausible scenarios and the identification of robust assumptions. These are included in the MetaScan on “The Future of Asia” which integrates the high level insights and policy challenges and opportunities from all four cluster studies (economic, energy, geostrategic, social).

The key changes and potential policy challenges and opportunities explored in this study are intended to be provocative in order to stimulate thinking among public servants about the future. They do not reflect a view of the most likely shape of change in Asia or consequences for Canada, but rather plausible developments that merit consideration. While this stud’s development involved participation and contributions from officials across multiple departments within the federal public service of Canada, the contents of the study do not necessarily reflect the individual views of participants or of their respective organizations.

Introduction

Asia is characterized by the wide contrast between its deeply-entrenched system of discrete nation-states, and its high connectivity with the global economy. On one hand, this disparity explains much about the origins of its numerous simmering inter-state tensions; on the other hand, it exemplifies aspirations for greater regional and global economic integration. Finding a consensus on how to reconcile this gap to encourage further economic development is a primary pre-occupation for the region’s geo-strategists.

Driven by significant economic, defence and security changes in the region and beyond, Asia has become a centre of geopolitical power. Asian countries are undertaking initiatives to foster greater regional economic integration and security cooperation that could reshape the geopolitical dynamics of the region and the world over the next 10-15 years. Asian countries are also investing heavily in military modernization on the land, sea, air and space fronts, which may alter the regional and global military balance in the years to come.

At the same time, Asian governments may be preoccupied with the rapid growth and convergence of non-traditional security threats such as cyber security issues, food and water insecurity, catastrophic climatic events and natural disasters, as well as the emergence of increasingly networked extremist and organized crime groups. Addressing these challenges and mitigating potential disruptions may test the collective capacity of Asian governments and non-state stakeholders, as these threats do not necessarily respect international borders.

This study, by no means exhaustive, identifies and explores some of these significant geostrategic shifts in Asia, with a view to understanding the implications for Canadian foreign, defence and security policy in the next 10-15 years.

The following table summarizes the key geostrategic changes (insights) that are shaping Asia and the potential policy challenges and opportunities for Canada addressed in this study.

Summary of Key Geostrategic Changes in Asia (Insights) and Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

Key Geostrategic Changes in Asia (Insights)

Asia’s shifting regional architecture

Efforts to build pan-Asian institutions and foster integration across a range of shared interests could allow Asia to play a dominant role in shaping a new global order.

Competing norms and interests in regional trade

The rise of regional trade agreements may undermine global trade norms and regimes and result in a more complex web of bilateral, specialized and regional trade arrangements.

Asia’s role in altering the military balance

An increase in defence spending and military procurement in Asia, and the perceived relative decline in U.S. regional influence, could create a less stable regional geopolitical environment.

Non-traditional threats defy conventional notions of security

Non-traditional security threats are becoming increasingly complex and combining in new ways that could overwhelm the ability of some Asian governments to deal with them, potentially compromising regional stability.

From state failure to regional instability

There is a growing risk of state collapse and lawlessness in a number of fragile Asian states that could cause significant disruption to the region and draw major powers into conflict.

Cyberspace as a new battleground for geostrategic supremacy

As cyberspace becomes a new battlefront for espionage and military conflict, the Internet could become fragmented or insecure for financial transactions and e-commerce.

Water scarcity leading to tensions and trade-offs

Long-anticipated water shortages in Asia could soon reach crisis levels, becoming a source of potential conflict and significantly affecting agriculture, fisheries and energy production.

Cities are key drivers of regional soft power in Asia

The extraordinary growth of Asia’s cities and proactive management of their “soft power” is transforming diplomatic relations in the region.

Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

Closing window to influence

There is a closing window of opportunity for Canada to influence the development of Asia’s regional institutions and architecture before they start to re-shape global norms and practices.

Maintaining flexibility in adapting to overlapping trade regimes

The lack of global momentum to galvanize support for a grand multilateral trade bargain means that free trade agreements will likely offer Canada the best potential for trade liberalization.

Canadian military engagement in Asia

Canada may need to establish deeper military and security partnerships with Asian countries to help promote and maintain its interests in the region.

Managing complexity in an age of converging security threats

The proliferation and convergence of security threats could lead to cascading effects making it extremely difficult for Canadian policy-makers to anticipate disruptive change in Asia and make informed, timely decisions.

Addressing Asia’s regional instability with strategic engagement

Canada may have to develop an over-arching, enduring and comprehensive Asian engagement strategy that is flexible, innovative, and context-specific.

Maintaining cyber security in the new digital era

An increasingly interdependent cyber world could expose strategic sectors to greater vulnerability and risk, and demand new governance models.

The next oil – water as Canada’s strategic advantage

Canada has a potential strategic advantage in harnessing its abundant water reserves as Asian countries seek access for commercial, industrial and basic needs.

Aligning multiple agendas to advance Canada’s strategic role in Asia

The varying perceptions among Canadian policy makers at all levels, various stakeholders and citizens may result in polarized visions of Canada’s engagement with Asia.

Key Changes in Asia (Insights)

Asia asserts its role as a global rule-maker

Emerging pan-Asian economic institutions, along with new trade agreements and security arrangements, could disrupt the existing global governance system by providing alternative forums and models to western-dominated institutional structures, relationships and norms.

Asia’s shifting regional architecture

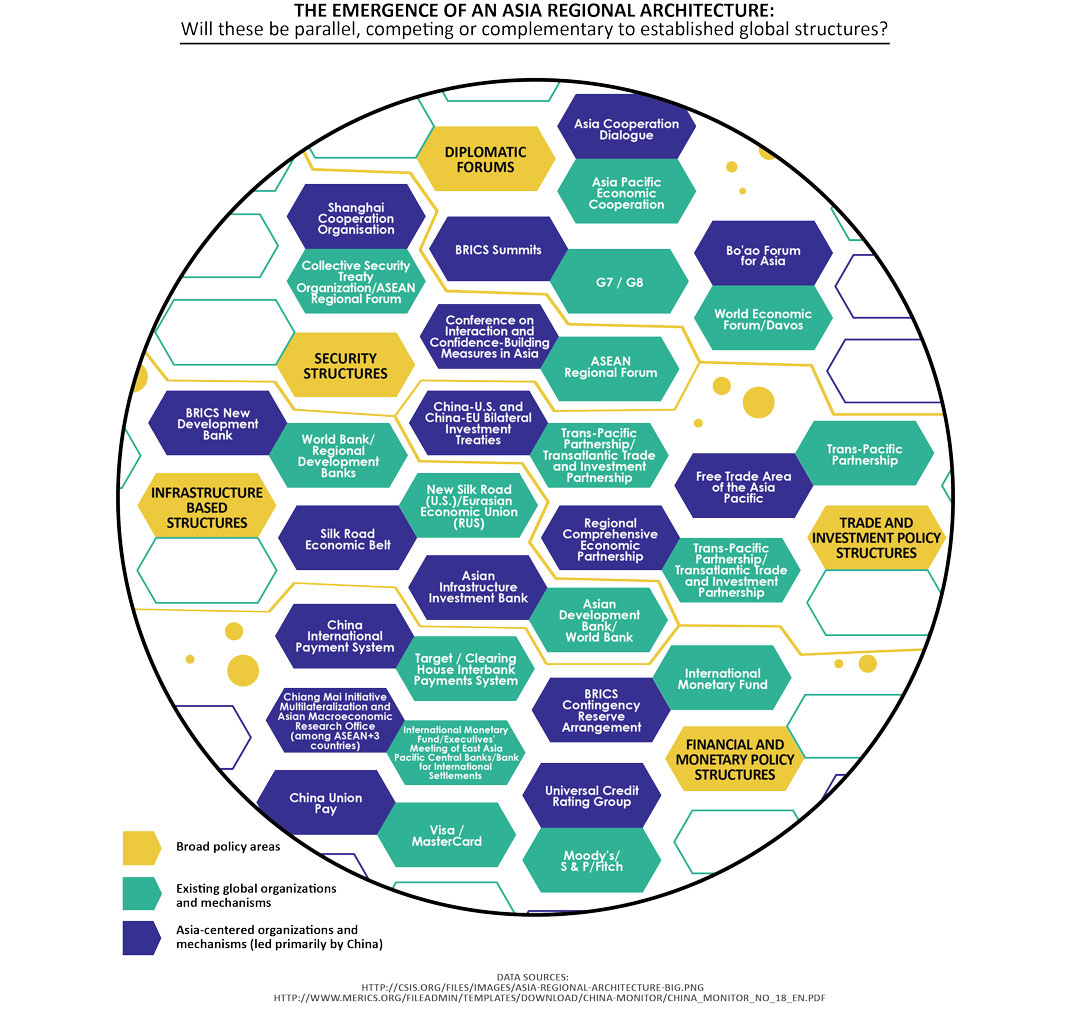

Efforts to build pan-Asian institutions and foster integration across a range of shared interests could, if successful, allow Asia to play a dominant role in shaping a new global order. Initiatives to further enhance Asian economic integration are well underway. The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN)1 continues to advance economic integration within the group and throughout the region, playing a critical role in the development of an emerging Asia-Pacific multilateral order.2 China is likewise undertaking initiatives to boost connectivity across the region, by, for example, investing in and promoting the Silk Road Economic Belt(link is external) initiative that would connect significant parts of Asia to Eastern Europe.3 In addition, new regional institutions centered on Asia are emerging, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank(link is external)(AIIB). China, eager to bolster its regional influence, is driving many of these pan-Asian initiatives (see Figure 1 for details of Asia’s emerging regional architecture).4

Similarly, ongoing cooperation on a range of security-related issues could act as strong foundations for diplomatic and security cooperation (e.g., through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization [SCO] and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia [CICA]). A number of calls for the creation of a regional multilateral architecture (i.e., the “Asian security concept(link is external)”) based on Asian collective needs and in accordance with Asian experience, suggest efforts are being made to find regional solutions to regional problems.5 Some of these institutions may exclude western nations altogether, while others are more inclusive (e.g., East Asia Summit, ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting-Plus, and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation).

Given the increased influence of Asian countries in global affairs, the emerging regional architecture could provide alternatives to western-based international institutions.

Figure 1 – The Emergence of an Asia Regional Architecture

As a result, international consensus on the values, norms, rules and principles, which underpin the global order, may be broadened or redefined (e.g., by providing more technocratic approaches to governance, altering principles of non-interference, or empowering collectivist approaches to individual rights).6 As expectations within China and India shift to better reflect their changing roles from rule-takers to rule-makers, Asia’s growing global influence could either directly or indirectly impact existing human rights conventions, security treaties, international regulations and trade protocols. This could result in a system of international norms rooted in pragmatism and self-interest rather than idealism and individual freedom, potentially eroding the primacy of international law over national law. As major Asian countries become more active in shifting global norms, institutional and financial support may be used as instruments of political influence and control. In other cases, tensions could emerge as major Asian powers attempt to dominate and shape new regional institutions.

Competing norms and interests in regional trade

The rise of regional trade agreements may undermine global trade norms and regimes and result in a more complex web of bilateral, specialized and regional trade arrangements. Asia is at the center of an intense competition to reshape global trade norms and regimes. International trade patterns are shifting to Asia, which is taking on an ever growing percentage of global trade flows. With a persistent stalemate at the World Trade Organization (WTO), bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs) are perceived by many countries as offering greater potential for increased trade liberalization. However, divisions have emerged between developed and developing countries as to how the global trade architecture should look. Advanced economies like the U.S. are pushing for ambitious trade agreements that reflect the rise of global value chains and address a broader range of issues including ‘behind-the-border’ non-tariff and regulatory barriers. Many emerging countries like China are challenging the traditional FTA model by promoting trade agreements that are more limited in scope and ambition, and that exclude more sensitive sectors.

For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – which has detailed provisions on state owned enterprises and intellectual property rights – is directly challenging China’s state capitalism development model by locking-in market-oriented reforms. In response, the China- and ASEAN-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is seen as an alternative trade model to the TPP that excludes the U.S. This may pose a challenge to some RCEP-TPP crossover countries, such as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam, as both agreements may reflect conflicting trade provisions and diverging paradigms and geopolitical allegiances.7 Recent initiatives by China(link is external) to resurrect the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) seek to undercut the TPP from becoming the foundation of regional trade and economic integration and to position itself on an equal footing with the U.S. in any Asia-Pacific regional trade deal.8 These overlapping trade blocs represent a departure from the most favoured nation principle and run the risk of serving as barriers to greater global integration rather than as building blocks towards that objective. Over the coming years, this impasse could bolster trade between developing countries to the detriment of the U.S. and the West. This may result in mounting pressure from North American and European exporters to accept less-ambitious trade agreements in order to secure market access.

Asia’s role in altering the military balance

An increase in defence spending and military procurement in Asia, coupled with the perceived relative decline in U.S. regional influence, could create a more complex and potentially less stable regional geopolitical environment. Globally, investments in military research, design, and development have propelled rapid innovation in unmanned aerial, ground and sea vehicles, robotics, orbital weaponry, biotechnology and nanotechnology, ballistic missile defence, as well as laser and electromagnetic pulse weapons.9 As a result, the U.S.’s comparative technological advantage over other countries is beginning to shrink.10 This is accelerated by military technological innovation shifting towards the private sector, with next generation dual-use technologies becoming available to a wide range of states, organizations and individuals.11 Asian states, especially China and India, may incorporate these technologies into their defence structures and security strategies, potentially upending longstanding regional balances of power as a result. For example, improved radar technology (e.g., anti-access/area denial platforms) along with advancements in maritime and submarine capabilities may allow some Asian states to erode, deny, and ultimately defeat traditional U.S. advantages in stealth military technology.12 Advancements in computer processing, which accelerate data collection and analysis, along with anti-satellite weaponry, which is capable of destroying civilian and military satellites in orbit, may play similar roles in levelling imbalances in military command and control between China, India, and the U.S.13

Future fictional vignette: News flash from the New York Herald (January 6, 2031) New York

Taiwan’s fate was sealed this morning after the UN Security Council failed to pass a resolution calling on China to remove its military forces from the island state. Though the resolution faced a certain Chinese veto and had largely been deemed a symbolic gesture to Taipei’s government-in-exile, the U.S., in a surprise move, abstained. “Our capacity to reverse Chinese gains in Taiwan is limited,” the U.S. Ambassador to the UN admitted, “though we do expect to continue building relevant and biting sanctions to make China reconsider this clear violation of international law.” China’s newly appointed Chief Executive of Taiwan, however, naturally applauded the Security Council’s decision, and again invited Washington to next month’s “Progress Summit” in Hong Kong. “China’s great reunification,” he added, “is a benefit to all. We encourage the U.S. President to clasp our open hand and help us build Asia’s New Beginning.” Taiwan’s demise, however, jolted the region’s remaining U.S. allies. Japan and Australia reaffirmed their commitment to the Pacific Mutual Defense Pact, expediting plans to launch a second jointly-operated aircraft carrier, while Singapore signaled its intention to leave the Non-Proliferation Treaty as early as next year. The enhanced military capabilities of any one of Asia’s major powers is unlikely to surpass that of the U.S. or NATO in technical terms (see Figure 2 for details on Asian military budgets and expenditure). However, they could become sufficiently robust to transform Asia’s geostrategic environment(link is external).14 Rebuffing U.S. supremacy, some Asian states may also seek to project military power beyond their borders by establishing foreign bases and building blue-water infrastructure overseas (e.g., China’s investment in Sri Lanka’s Hambantotat Port and Colombo South Container Terminal, Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, and Bangladesh’s Chittagong Port; India’s strategic interests in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, as well as Iran’s Chabahar port).15 Rising Asian military capability and assertiveness, along with the relative decline in U.S. regional influence, may force some Asian states to revisit their bilateral and multilateral alliances and security arrangements, further complicating an already competitive and tenuous regional military balance.16

Figure 2 – The percentage Change in Asian Military Budgets (2003 – 2013)

This diagram visually shows the percentage change in Asian military budgets from 2003 to 2013. It shows a heat map of Asia. The list of countries with the highest positive percentage change in military budgets to the lowest negative change are as follows: China with a change of +228%, Vietnam with a change of +130%, Russia with a change of +125%, Bangladesh with a change of +102%, Indonesia with a change of +92%, Thailand with a change of +78%, Sri Lanka with a change of +75%, India with a change of +63%, South Korea with a change of +55%, The Philippines with a change of +43%, Pakistan with a change of +30%, Singapore with a change of +22 %, Australia with a change of +21 %, Taiwan with a change of +8 %, and Japan as the only country with a decrease in budget with a minus 20 %. In comparison, United States had an increase of 26% and Canada had an increase of 12%. Next to the heat map are two tables. The top table is entitled “Top Asian Military Expenditures (USD, 2013)” and it lists the following expenditures: China with $188.5 billion, Russia with $87.8 billion, Japan with $48.6 billion, India with $47.4 billion, South Korea with $33.9 billion, and Australia with $23.9 billion. To note: U.S. spent $640.2 billion and Canada spent $18.5 billion. The second table is entitled “Estimated Nuclear Weapons Inventories, Asia 2014.” It lists the following countries: Russia with 8,000 weapons, China with 250 weapons, Pakistan with 100-120 weapons, India with 90-110 weapons, and North Korea with less than 10. To note: U.S. was in possession of an estimated 7,300 warheads.

Asia compelled to move beyond narrow definitions of security

Non-traditional threats in Asia, both in the physical and virtual worlds, are challenging conventional notions of state power and control, requiring a more holistic interpretation of security.

Non-traditional threats defy conventional notions of security

Non-traditional security threats are becoming increasingly complex and combining in new ways that could overwhelm the ability of some Asian governments to deal with them, potentially compromising regional stability and distorting global economic development in the process. Asia’s complex security threats (e.g., insurgency, endemic corruption, organized crime, terrorism, radicalization, irregular migration, illicit capital flows, entrenched poverty, water and food scarcity, energy shortages and health pandemics) are not only proliferating at unprecedented rates, but are converging in unpredictable ways. The non-linear interaction of these seemingly unrelated threats is extremely difficult to measure and interpret, even for seasoned security and policy analysts. For example, the proliferation of drone technology and encrypted communication, along with the ability of 3D printing technology to produce automatic weaponry, could intensify conflict as terrorist and criminal networks improve their ability to operate across Asia.17 Furthermore, the evolution of these “hybrid” threats could mean that Asian governments will need to focus on domestic security challenges within cities, in addition to interstate conflict.18 In addition, the hyper-connectivity of international financial services(link is external)may further incentivize illegitimate land seizures, the destruction of fragile ecosystems, and the illegal “capture” of state assets. For instance, Asia reportedly lost $2.6 trillion to illicit financial flows between 2003 and 2012.19 Thousands of corrupt officials and their families have already migrated to a number of preferred destination countries, generating real estate “bubbles” and other forms of economic speculation.20

There is a growing risk that the cumulative effects of existing and emerging threats, especially in Asia’s burgeoning cities, may overwhelm some governments and necessitate a paradigm shift in contemporary security and strategic thinking. Several Asian megacities such as Dhaka, Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), Mumbai, and Chennai are already at risk of extreme climate events(link is external) that could displace tens of millions of people by mid-century.21 In these overlapping governance spaces, security policies may have to be re-evaluated to address long-term issues regarding reliable waste water treatment, distributed energy grids, equitable education and health care provision, and environmental sustainability, alongside the short-term application of coercive para-military force.

From state failure to regional instability

There is a growing risk of state collapse and lawlessness in a number of fragile Asian states that could cause significant disruption to the region and draw major powers into conflict. Asia has eleven of the world’s most fragile states (link is external)(notably Afghanistan, Pakistan, North Korea, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Uzbekistan) that encompass over 570 million people and include two states with nuclear weapons capabilities.22 The growing interconnection between ethnicity and politics(link is external), the rising relative power of violent non-state actors, and marginalized populations increase the likelihood that state implosion will lead to broader regional instability. Civil war, ethnic strife and state weakness could lead to the formation of cross-border pockets of ungoverned territory (e.g., Afghanistan–Pakistan–Uzbekistan, Myanmar–Bangladesh–Nepal), and potentially cascade into sub-regions of protracted instability (e.g., spanning from Central to Southeast Asia).23 This breakdown in state control could empower warlords, militants and ethnic or tribal groups, and lead to the black market diffusion of pillaged armaments including chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) weapons.24 As state power and control over territory and borders contract, population displacement, human rights abuses, lawlessness and criminality could increase.25 Regional instability could also lead to increased levels of piracy, which could heighten military tension between major powers drawn in to address these or similar situations. Alternatively, the threat of disruption posed by fragile states could serve as an impetus for action and collaboration by Asian powers to bolster the stability of the region’s weakest governments.

Cyberspace as a new battleground for geostrategic supremacy

As cyberspace becomes a new battlefront for espionage and military conflict between states, the Internet could become fragmented or insecure for business and financial transactions, slowing the evolution of e-commerce in the process. Several Asian countries, such as China, Taiwan, Australia, South Korea, North Korea, India and Pakistan, have developed sizable cyber war capabilities.26 As a result, cyber warfare(link is external) is likely to play a more critical role in future armed conflicts.27 We may be witnessing the emergence of a new phase in cyber military-affairs, as digital technology and the Internet of Things create new online vulnerabilities, which enable novel forms of economic warfare and industrial espionage, and introduce innovative ways to target critical infrastructure.28 Declining costs, ease of accessibility, and digital anonymity may also incentivize less-powerful Asian countries to engage in aggressive or predatory behaviour, notwithstanding continued public and private investments in cyber-defensive capabilities. Additionally, the cyber-offensive capabilities of private Internet hackers, state proxies and “virtual vigilantes” are maturing faster than the defensive capabilities of some states, further complicating an already volatile situation.29

Ultimately, the co-existence of external and internal threats could lead to the “territorialization” of cyberspace, as traditional Asian powers move to build “cyber-walls” around their domestic networks in an attempt to protect national security and ensure social stability.30 The construction of cyber-fortifications (link is external) and the creation of localized intranets could undermine the very essence of the Internet (e.g., open, transparent, inclusive) and negatively affect international economic and financial stability. Alternatively, the persistence of sophisticated cyber-incursions and cyber-attacks might inhibit risk-taking among Asian businesses to the extent that they limit international partnerships and e-commerce, further impeding economic growth.31 Some of the most vulnerable countries might take it upon themselves to fortify their cyber-domains, potentially denying “e-citizenship” rights and exacerbating wealth disparities, the digital divide, and ethno-social grievances.32

Water scarcity leading to tensions and trade-offs

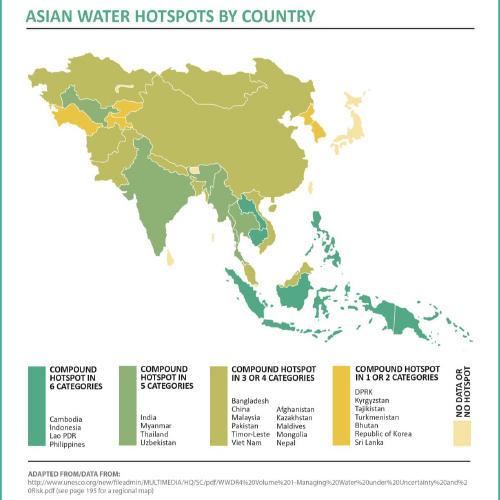

Long-anticipated water shortages in Asia could soon reach crisis levels, becoming a source of potential conflict and significantly affecting agriculture, fisheries and energy production. Water scarcity in Asia is worsening due to pollution, illicit dumping of toxins, increased consumption as a result of uncontrolled urbanization, poorly-coordinated trans-boundary usage, climate change, and rising energy and industrial demands (see Figure 3 for Asia’s water hotspots).33 Many countries and regions in Asia are pumping ground water at unsustainable rates and have already passed “peak water”, with growing demand outweighing the available supply. As a result, they will be unable to sustain current use trajectories for much longer, resulting in a growing source of inter- and intra-state tension(link is external), especially in Central and South Asia.34 The trade-offs between water for agricultural, energy and industrial usage may present policy dilemmas for economic growth objectives, as governments will be challenged to optimize allocation of scarce water amongst competing users and national goals. Impacts on the salinity of water and quality of soil could also lead to food security concerns. While in some cases existing and new technologies may mitigate the need for water in certain industries, the lack of cheap water could significantly shift the economic and political dynamics of the region by increasing the relative advantage of upstream countries, potentially leading to conflict.35 For example, through its multiple dam-building projects on the Tibetan Plateau(link is external), a source of the Brahmaputra and Mekong rivers, China may position itself as the dominant water broker for up to 40% of the world’s population.36

In Central Asia, Uzbekistan has threatened that dam projects in upstream countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan could instigate war in the event that its agricultural exports are negatively impacted by water shortages.37

Figure 3 – Asian Water Hotspots by Country

This diagram is entitled “Asian Water Hotspots by Country.” It is a heat map of Asia showing in different colour shades the amount of compound hotspots. The compound hotspots in 6 categories are: Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, and Philippines. The compound hotspots in 5 categories are: India, Myanmar, Thailand, and Uzbekistan. The compound hotspots in 3 or 4 categories are: Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Pakistan, Timor-Leste, Viet Nam, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Maldives, Mongolia, and Nepal. The compound hotspot in 1 or 2 categories are: DPRK, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Bhutan, Republic of Korea, and Sri Lanka. The remaining Asian countries either had no hotspot or no data recorded.

Asia’s urban revolution alters diplomatic relations

Asia’s burgeoning cities, some exceeding the size of nation states, are emerging as regional powerhouses of innovation and development, potentially transforming economic and diplomatic relations.

Cities are key drivers of regional soft power in Asia

The extraordinary growth of Asia’s cities and proactive management of their “soft power” is transforming diplomatic relations in the region. Asia is home to 16 of the world’s 28 megacities (link is external)(greater than 10 million residents) with over half of these located in India and China.38 Asia’s municipal leaders are proactively leveraging the “soft power” of their cities (e.g., identity, architectural heritage, quality of living, social diversity, tourism, sports, food, civic advocacy) to attract both international investment and the world’s most creative thinkers. For example, within the next decade China may be home to 29 of the world’s 75 most dynamic cities (e.g., those that incorporate smart infrastructure and foster a knowledge-based economy), and include four of the top five.39 Asia’s inter-urban influence is a key driver of economic, political and social change across the region. A number of city networks have formed without official national endorsement and municipal officials routinely lead trade delegations and heavily-influence international policy discussions.40 Indian and Chinese cities have, for instance, set up non-diplomatic offices abroad with a view of attracting tourism and investment capital.41,42

Cities have an increasing stake in human rights, and environmental and non-traditional security issues, and may increasingly influence national positions and strategies as a result. The Asian Network of Major Cities 21 (ANMC21), for example, leads joint projects on a range of topics including crisis management, environmental degradation and industrial development. These informal arrangements suggest that traditional interstate competition could be tempered by more cooperative governance models between cities of different nations, even if the city networks are far from uniform. As the mutual benefits of city-to-city diplomacy begin to cross national borders, Asia’s elite governance models, such as the “Singapore Consensus(link is external)” could begin to unravel.43 In the same way that small Asian states use “soft power” to leverage their importance among more powerful neighbours, major cities, such as Tokyo, Seoul, Shanghai, Chengdu and Hong Kong, could place limits on the scope for independent action proposed by national governments.

Future fictional vignette: Floating Cities Grounded by International Politics, The International Maritime Observer (August 31, 2027)

We are reporting live off the coast of Sri Lanka. The 5th Annual Meeting of the International Floating Cities Condominium concluded today in the Indian Ocean without issuing a formal communiqué. Asian country representatives protested against a motion introduced yesterday by EU, Russian, and North American delegates concerning the certification process of floating armouries. Representatives who filed the motion argue the need for internationally recognized and enforceable standards for the private security firms that provide security for many floating cities. The Asian delegates objected to the motion as a cynical move by western countries to intervene in Asia’s internal security affairs. Representatives from the Floating Cities Condominium also stated that they remain breakaway republics and wish to remain independent of international politics, which is precisely why their constituents moved off the mainland in the first place.

Policy Challenges and Opportunities for Canada

The rapid changes that may occur in Asia over the next 10-15 years will present Canada with a range of challenges and opportunities. This section highlights those that may be particularly surprising and unexpected.

Closing window to influence

There is a closing window of opportunity for Canada to influence the development of Asia’s regional institutions and architecture before they start to re-shape global norms and practices. The next 15 years is likely to be a watershed period in establishing the regional norms and institutions that will guide Asia’s rise as one of the world’s most influential continents. Canada has an opportunity to influence the outcome of this conversation by leveraging its niche capabilities (e.g., resource management, financial services, governance, environmental protection, supply chain resilience) in order to gain influence and better protect its interests within the region and the broader G2 (China-U.S.) world. The challenge will lie in ensuring that Canada allocates sufficient resources to support strategic engagement in the region beyond negotiating trade agreements. In some cases, Canada may have to make some difficult trade-offs to secure influence such as diverting financial and diplomatic investments from other regions (i.e., Europe, the Middle East, the Americas) towards Asia or increasingly recognizing the voice of Asian observer states in the Arctic Council in exchange for trade access and lucrative investment opportunities.44 Furthermore, some Asian middle powers (i.e., Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea and Vietnam) are likely to play an increasing role in countering the influence of larger powers on the regional and world stages. Working with these middle powers may be the entry point for Canada in leveraging its niche capabilities to influence the development of the emerging Asian geopolitical architecture and enhance its country-to-country relationships in the region.

Maintaining flexibility in adapting to overlapping trade regimes

The lack of global momentum to galvanize support for a grand multilateral trade bargain means that FTAs will likely offer Canada the best potential for trade liberalization, although these arrangements often lead to suboptimal outcomes from a trade liberalization perspective. FTAs represent a departure from the most favoured nation principle and can cause trade diversion and displacement. They also differ dramatically in terms of scope and quality, and increase the risks of inconsistencies in rules and procedures (e.g., rules of origin) among FTAs themselves and between FTAs and the multilateral framework. In the Asian context, Canada may need to remain flexible in order to adapt to different and overlapping trade regimes with varying levels of ambition. In some cases, a regional trade agreement in Asia would result in lower tariff and non-tariff barriers and harmonization across countries that could be attractive to Canada’s businesses, who currently find it challenging to operate in an increasingly diverse and complex region. However, the absence of a broad multilateral framework to guide regional trade negotiations in Asia could force Canada to navigate an operating environment dominated by “hub-and-spoke” configurations, where bigger players like China and the U.S. set the tone and scope of the negotiations. Canada may need to inject flexibility to adapt its negotiating template (currently based on the North American Free Trade Agreement and the more recent Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union) to varying circumstances and trading partners at different levels of development.

At the same time, the establishment of regional agreements that exclude Canada (i.e., RCEP), may require it to rely on regional emissaries or third-party intermediaries to compete with the growing influence of countries, principally Australia and New Zealand, that are adept at exploiting opportunities in Asia. In some cases, many Asian countries may seek technology transfer from Canadian companies in exchange for access to their markets. In the long-term, this may result in some Canadian industries losing all or part of their markets due to the “leapfrogging” of Asian capacity based on these technology transfers. Canada may either have to accept these trade-offs as inevitable and plan for further market diversification, or bolster intellectual property protection at the possible expense of market access.

Canadian military engagement in Asia

Canada may need to establish deeper military and security partnerships with Asian countries to help promote and maintain its interests in the region. Canadian peacetime military engagement in Asia is relatively small compared to other regions. Notwithstanding Canada’s long history of involvement in Asian security and peacekeeping affairs (e.g., the defence of Hong Kong, Korean War, UN and NATO missions in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan), new relationships and capacities may need to be explored and built to enable Canada to participate more effectively with a range of Asian states in future humanitarian or security operations. The imbalance between Canada’s commercial, political and security engagement in the region hinders its ability to play a strategic role in Asia. Worse, Canada increasingly risks being painted as a regional security “free-rider”, benefiting from the stability provided and upheld by American, Japanese, Korean and Australian investments.

Enhanced military engagement has the potential to increase familiarity with friendly Asian militaries, improve Canada’s profile in the region, demonstrate a commitment to areas of mutual interest, and facilitate cooperative responses to humanitarian crises and natural disasters. Canada has a variety of options to consider and weigh, from shifting its primary military focus away from Europe and the Middle East, to identifying opportunities within Asia where Canada’s capabilities, historical partnerships (e.g., the “Five Eyes”), and special relationship with the U.S. might allow it to effectively contribute to multilateral efforts in the region. Canada could also explore increasing its investment in joint military, security and training exercises with particular Asian countries in ways that effectively leverage Canadian strengths (e.g., electronic surveillance and intelligence collection and analysis, Special Operations Forces, military training, civil-military relations, crisis management). Working through and alongside Canada’s existing defence and security partnerships may allow Canada to find creative ways to engage with non-traditional Asian military partners without jeopardizing traditional security relationships.

Managing complexity in an age of converging security threats

The proliferation and convergence of security threats could lead to cascading effects (e.g., terrorism-crime nexus, climate-induced migration, food-energy security) making it extremely difficult for Canadian policy-makers to anticipate disruptive transformations in Asia and make informed and timely decisions. A poor situational awareness of Asia’s evolving threat environment could impair strategic decisions in Canada concerning emerging risks and opportunities and may inhibit policy consensus when it is most needed. Policy-makers who lack a sufficient appreciation of “hybrid” threats, or the “event pathways” along which they travel and intersect, may struggle to anticipate paradigm shifts and fail to understand the ways in which conventional notions of security are shifting. In crisis situations, decision-making within Canada could also become paralyzed due to contrasting threat perceptions and intense jurisdictional disputes at the federal level. Moreover, Canada’s reputation as a reliable partner and responsible stakeholder in Asia could be seriously damaged if its security, humanitarian and foreign aid interventions are judged to be insufficiently responsive, agile or resilient. As Canada-Asia networks continue to expand in unexpected ways and into unfamiliar policy areas, decision-makers may be forced to re-examine the relevance of existing governance models and the effectiveness of organizational structures that were designed for a more orderly and predictable world.

Addressing Asia’s regional instability with strategic engagement

The risk that destabilization in one part of Asia may have debilitating consequences in neighbouring countries may necessitate that Canada develop an over-arching, enduring and comprehensive Asian engagement strategy that is flexible, innovative, and context-specific. The possibility of cascading political instability in parts of Asia might compel Canada to redefine its role in the region from an ad-hoc first responder to a dependable and permanent regional stakeholder. A meaningful shift in focus towards Asia may require that Canada pivot away from Europe by redeploying its military, disaster management and stabilization resources to Western Canada, or by pre-positioning and maintaining these assets in the Asia-Pacific region. While conventional military force will remain integral to any future disaster management strategies, “soft power” solutions (e.g., building community resilience, anti-corruption strategies, ensuring food security) will likely increase in demand as intervening states grapple with alleviating the chronic pre-conditions that weaken communities and states. Canada may need to further pursue and solidify lasting partnerships with established and emerging institutions (e.g., the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, International Migration Organization) and multi-national corporations in order to assist Asian stakeholders in building governance capacity and resilience. In this context, however, maintaining strategic coherence among and between foreign donors may become difficult to achieve. Canada and its partners may confront legal, political, and ethical dilemmas as to when to intervene, on whose behalf, to what degree, for what purpose, and under what specific conditions. Likewise, if demand for humanitarian assistance exceeds the capacity of regional aid agencies and non-government organizations, Canadian efforts may have to be tailored and contextualized to remain cost-effective. Decision-making authority might need to be further delegated to front-line program managers as context-specific issues demand more bottom-up, flexible and adaptive approaches from Canada.

Maintaining cyber security in the new digital era

An increasingly interdependent cyber world could expose strategic sectors to greater vulnerability and risk, and demand new governance models. A free and open Internet provides a relatively low-cost, risk-free environment for a wide spectrum of risk-disruption and intelligence collection activities.45 In the absence of incredibly reliable trace-back software and capabilities, or of more traditional intelligence methods to attribute the source of an attack, Canada may have difficulty responding effectively to this rapidly evolving threat environment. Multilateral governance arrangements such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a non-state organization based in the U.S., may partially mitigate some cyber threats. However, maintaining state-of-the-art technology to ensure that adequate prevention capabilities are maintained may cause serious economic burden. Furthermore, safeguards (e.g., internationally recognized rules of engagement for cyber war) implemented today could soon become progressively less effective unless “weak links” in the system (e.g., software vulnerabilities) are addressed using advanced programming capabilities (e.g., automated software programming).

It is also quite plausible that cyberspace could become more heterogeneous, consisting of a globally connected Internet for general purposes supplemented by separate and more secure national “intranets” (e.g., an Internet interface would be retained but the individual networks would lack any real-time connections or compatible operating protocols).46 In this context, Canadian policy-makers may consider the feasibility of negotiating “hybrid” governance frameworks with the private sector in a way that enables the entire system to attribute threats at the source and to better defend itself against predatory actors. This may involve some difficult trade-offs and governance challenges since private sector businesses are far more exposed to cyber-related risks than the public sector. Given that cyber research in the public sector remains fragmented and seriously underfunded, Canada may have to extend its current whole of government approach by partnering with Asian government agencies, corporations, or research institutes. However, any tangible benefits that the government may derive in terms of responsiveness, flexibility and situational awareness might be more than off-set if personal privacy is perceived to have been sacrificed in the interest of protecting Canada’s sovereignty.

The next oil – managing water to Canada’s strategic advantage

Canada may have to make strategic decisions regarding its abundant water reserves as Asian countries seek access for commercial, industrial and basic needs. In coming years, Asian countries may increasingly look to Canada for their water-intensive production or processing activities.47 Managing investment and access to water resources will be crucial in harnessing Canada’s strategic water advantage. Possible economic opportunities include attracting water-intensive industries to Canada, securing international markets for water-demanding food stocks, and the production of goods with high embodied water content or “virtual water” (the total volume of water required to produce and process a commodity or service).48 However, the continued lack of a federal-provincial consensus on the strategic importance of water and appropriate use and access rights, could lead to sub-optimal decision-making as jurisdictions compete for water-intensive investments, undercutting the value of water and resulting in unsustainable extraction practices. In addition, Canada’s experience in managing shared waters with the U.S. through the International Joint Commission could serve as an example of best practices to help defuse trans-boundary water tensions in the Indo-Pacific maritime region.

Aligning multiple agendas to advance Canada’s strategic role in Asia

The varying perceptions among Canadian policy makers at all government levels, various stakeholders and citizens may result in polarized visions of Canada’s engagement with Asia. A number of Canadian provinces, territories and cities are making significant economic and diplomatic investments in Asia, on the basis that they are better placed to harness the specific trade and investment opportunities relevant to their economic needs. Municipal and provincial authorities are signing agreements with various levels of governments in Asia (not just with their own counterparts) and leading trade missions to the region.49 Likewise, First Nations groups are currently exploring ways to strengthen their relationships with Asian countries looking to invest in Canada.50 At the same time, in some parts of the country, Canadians’ attitudes about Asia reveal a risk-aversion towards strategic engagements with the region compared to traditional partners.51 In some cases, unilateral and uncoordinated representation of Canada’s interests in Asia could generate an incoherent view of Canada’s actions and priorities on the world stage, diminishing the country’s international reputation. Alternatively, the federal government could remain a useful vehicle to help Canadian citizens, businesses, governments and other stakeholders identify, leverage and advance their shared interests in Asia. The rise of Asian megacities and other non-state actors (such as multi-national corporations) may force Canada to better institutionalize, formalize, and incorporate para-diplomacy (e.g., sub-national, non-state foreign relations) into its regional engagement strategy. A key policy challenge for Canada will be formulating a comprehensive Asia strategy and securing a stable foothold among Asia’s “rising tigers” (e.g., ASEAN, India, Vietnam, and Indonesia) before they become even more politically and economically integrated.

Notes

1 The Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) is made up of the following 10 countries: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

2 Mahbubani, Kishore and Rhoda Severino. 2014. “ASEAN: The way forward.(link is external)” McKinsey & Company Insights. May 2014.

3 Page, Jeremy. 2014. “China Sees Itself at Center of New Asian Order.(link is external)” The Wall Street Journal. November 9, 2014.

“China to establish $40 Billion Silk Road infrastructure fund.(link is external)” Reuters. November 8, 2014.

4 “Infrastructure Investment Bank.(link is external) The Indian Express. October 24, 2014.

5 Panda, Ankit. 2014. “China creates new ‘Asia for Asians’ security forum.(link is external)” The Diplomat. September 15, 2014.

Chin, Curtis. 2014. “Xi Jinping’s ‘Asia for Asians’ Mantra Evokes Imperial Japan.(link is external)” South China Morning Post. July 14, 2014.

“New Asian security concept for new progress in security cooperation.(link is external) Full Text of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech delivered at the Fourth Summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (May 21, 2014). Chinese Foreign Ministry. May 28, 2014.

6 Jong-Wha, Lee. 2014. “China’s new world order.(link is external) Economia. November 13, 2014.

Glaser, Bonnie. 2014. “Notes from the Xiangshen Forum.(link is external) Center for Strategic & International Studies: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. November 25, 2014.

“Why China is creating a new ‘World Bank’ for Asia.(link is external)” The Economist. November 11, 2014.

Parameswaran, Prashanth. 2014. “The truth about China’s ‘Big, Bad’ infrastructure bank.(link is external) The Diplomat. October 16, 2014.

Desker, Barry. 2013. “Why the world must listen more carefully to Asia’s rising powers.(link is external) Europe’s World. February 1, 2013.

Werth, Matthew. 2013. “Effects of Collectivist vs. Individualist Approaches to Ethics on Sino-US Relations.(link is external)” Global Ethics Network. April 29, 2013.

Vanoverbeke, Dimitri and Michael Reiterer. 2014. “ASEAN’s Regional Approach to Human Rights: The Limits of the European Model?(link is external) in European Yearbook on Human Rights 2014. (pg. 188)

7 Emerson, David. 2013. “Comfortable Canada: But for how long?(link is external)” Policy Options. July-August 2013.

Kelsey, Jane. 2013. “US-China Relations and the Geopolitics of the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreements (TPPA).(link is external)” Global Research. November 2013.

8 Solis, Mireya. 2014. “China flexes its muscles at APEC with the revival of FTAAP.(link is external)” East Asia Forum. November 23, 2014.

9 Job, Brian. 2014. “Anticipating ‘disruptive change’ for Asia, 2030.” Prepared for Policy Horizons Canada, 2014; Singer, P.W. 2009. Wired for War(link is external). New York City: Penguin Press.

10The Looming Robotics Gap(link is external)

11Every Country Will Have Armed Drones Within 10 Years(link is external)

New Pentagon Chief Carter to Court Silicon Valley(link is external)12 Metrick, Andrew.2015. “A Cold War legacy: The Decline of Stealth,(link is external)” War on the Rocks (20 January 2015).

Bitzinger, Richard A. 2014. “Military Modernization in Asia,” in Strategy in Asia: The Past, Present, and Future of Regional Security, Thomas Mahnken and Dan Blumenthal, eds. (Stanford, Stanford University Press).

Yoshihara, Toshi. 2014. “Chinese Maritime Geography,” in Strategy in Asia: The Past, Present, and Future of Regional Security, Thomas Mahnken and Dan Blumenthal, eds. (Stanford, Stanford University Press).

13 Osborne, Hannah. 2014. “China planning ‘to militarize space’ against US Anti-Satellite Weapons(link is external)”, International Business Times. April 15, 2014.

14 Dowdey, John, et al. 2014. “Southeast Asia: The next growth opportunity in defense.” McKinsey Innovation Campus Aerospace and Defense Practice. February 2014.

“The impact of new military capabilities in the Asia-Pacific.(link is external)” International Institute for Strategic Studies: Asia Security Summit. May 31, 2014.

Page, Jeremy. 2014. “Deep threat: China’s submarines add nuclear-strike capability, altering strategic balance.(link is external)” Wall Street Journal. October 24, 2014.

Mead, Walter Russell. 2014. “The return of geopolitics: The revenge of the revisionist powers.(link is external)” Foreign Affairs. May/June 2014.

Roubini, Nouriel. 2014. “Global Ground Zero in Asia.(link is external)” CNBC. April 30, 2014.

15 Brewster, David. 2014. “The Bay of Bengal: The Maritime Silk Route and China’s Naval Ambitions.(link is external)” The Diplomat. December 14, 2014.

Singh, Abhijit. 2015. “Blue-Water Navies in the Indian Ocean Region.(link is external)” The Diplomat. January 21, 2015.

Sandilya, Hrishabh. 2014. “Inida, Iran, and the West.(link is external)” The Diplomat. November 8, 2014

Brewster, David. 2014. “Sri Lanka Tilts to Beijing.(link is external)” East Asia Forum. November 26, 2014.

Berkshire Miller, J. 2014. “China Making a play at Bangladesh?(link is external)” Forbes. January 3, 2014.

Smith, Jeff. 2014. “Andaman and Nicobar Islands: India’s Strategic Outpost.(link is external)” The Diplomat. March 18, 2014.

16 Tellis, Ashley, Abraham Denmark, and Travis Tanner (eds.). 2013. Asia in the Second Nuclear Age(link is external) (Washington, D.C., National Bureau of Asian Research, 2013).

Cronin, Patrick et. al. 2013. The Emerging Asia Power Web: The Rise of Bilateral Intra-Asian Security Ties(link is external), Center for New American Security. June 10, 2013.

17 Gillman, Louie. “3D-Printed An AR-15 Assault Rifle – And It Shoots Great!(link is external)” Business Insider (December 2013).

18 Kilcullen, David. 2013. Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerilla. London: Oxford University Press.

19 Cumulative illicit financial flows from Asia for the period 2003 to 2012 are estimated at $2.6 trillion. Losses in China alone are estimated at 1.08 trillion while the total for Russia is $211.5 billion from 1994-2011.

Freitas, Sarah and Dev Kar. 2013. “Russia: Illicit Financial Flows and the Underground Economy(link is external)” Global Financial Integrity. February 13, 2013.

IBTimes. 2012. “The Great Escape: Suspected Corrupt Bureaucrats (And Their Billions) Flee China in Droves.” June 6, 2012. http://www.ibtimes.com/great-escape-suspected-corrupt-bureaucrats-and-th…(link is external)

Rajagopalan, Megha. 2014. “Canada, China to sign deal on return of fugitives’ seized assets,(link is external)” Reuters. December 15, 2014.

20 Marr, Garry. 2014. “CMHC tackles foreign ownership in Canada’s housing market for first time(link is external),” Financial Post. December 16, 2014.

21 Mayer, Benoit. 2011. “The International Legal Challenges of Climate-Induced Migration: Proposal for an International Legal Framework(link is external),” Colorado Journal of Environmental Law and Policy. Volume 22; No. 3 .

22 Fund for Peace. Fragile State Index(link is external). 2015.

23 Rothkopf, David. 2014. “What if the United States had a Middle East strategy?(link is external)” Foreign Policy. August 11, 2014.

Harrison, Selig. 2008. “‘Pashtunistan’: The challenge to Pakistan and Afghanistan.(link is external)” Analyses of the Elcano royal Institute No. 37 (Real Instituto Elcano, Spain). April 2, 2008.

24 Rotberg, Robert (ed.). 2003. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences(link is external). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

25 “Global Governance Monitor: Armed Conflict(link is external).” Council on Foreign Relations Video. 2013.

26 Clarke, Richard A. 2010. Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What Do About it. New York: Harper Collins.

27 Limnell, Jarno. 2014. “NATO’s September Summit Must Confront Cyber Threats,” Breaking Defense(link is external).

28 Goure, Daniel. 2014. “Private Companies Will Be The Core Of A New “Offset” Strategy Against Cyber Attacks(link is external),” Lexington Institute. August 12, 2014.

Chickowski, Ericka. “Internet Of Things Contains Average Of 25 Vulnerabilities Per Device(link is external),” Dark Reading (July 2014).

29 Lynch, Justin. 2014. “The Counterinsurgency Paradigm Shift(link is external),” War on the Rocks Blog. November 20, 2014.

30 United Nations. 2014. “An International Code of Conduct for Information Security: China’s perspective on building a peaceful, secure, open and cooperative cyberspace(link is external)” Submission to the United Nations. February 10, 2014.

Lewis, James A. 2013. “Asia: The Cybersecurity Battleground(link is external).” Center for Strategic and International Studies. July 23, 2013.

Farnsworth, Timothy. 2011. “China and Russia Submit Cyber Proposal(link is external)” Arms Control Association. November 2, 2011.

Sterner, Eric. 2014. “China, Russia Resume Push for Content Restrictions in Cyberspace(link is external) World Politics Review. May 1, 2014.

31 Shackelford, Scott J. 2014. Managing Cyber Attacks in International Law, Business, and Relations: In Search of Cyber Peace. July 2014. London: Cambridge University Press.

32 Schnurer, Eric. 2014. “Welcome to E-stonia: Estonia shows what virtual citizenship could look like(link is external).” US News. December 4, 2014.

33 Asia Society. 2009. “Asia’s next challenge: Securing the region’s water future(link is external).” April 2009.

Kaiman, Jonathan. 2014. “China says more than half of its groundwater is polluted(link is external).” The Guardian. April 23, 2014.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. 2011. “Water availability and use – Statistical Yearbook for Asia and the Pacific 2011(link is external)”

34 Chellaney, Brahma. 2012. “Asia’s worsening water crisis(link is external).” Survival 54:2. April-May 2012.

Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs. 2014. “Water is a growing source of tension and insecurity across South Asia(link is external)” June 27, 2014.

Price, Gareth et al. 2014. “Attitudes to Water in South Asia(link is external)” Chatham House: The Royal Institute of International Affairs. June 2014.

“Growing water tensions in Central Asia.” Eurasia Review. September 15, 2014.

Wasleka, Sundeep. 2012. “Will water scarcity increase tensions across Asia?(link is external)” Forbes. October 1, 2012.

Brown, Lester. 2013. “The real threat to our future is peak water(link is external).” The Guardian. July 6, 2013.

Green, Peter S. 2012. “Peak Water: The rise and fall of cheap, clean H2O(link is external)” Bloomberg News. February 6, 2012.

Powell, Simon. 2010. “Thirsty Asia 2: How do we respond to peak water?(link is external)” CLSA Asia-Pacific Markets. January 2010.

35 Katz, Cheryl. 2014. “New Desalination Technologies Spur Growth in Recycling Water(link is external)” Environment360. June 3, 2014.

Nuclear Energy Institute. 2014. “Water Desalination(link is external).

36 Ninkovic, Nina and Jean-Pierre Lehmann. 2013. “Tibet and 21st Century Water Wars(link is external).” The Globalist. July 11, 2013.

Vidal, John. 2013. “China and India ‘water grab’ dams put ecology of Himalayas in danger(link is external).” The Guardian. August 10, 2013.

Dien, An. 2014. “Mekong River at risk as Laos forges ahead with dam-building spree(link is external).” Thanh Nien News. April 14, 2014.

37 “Growing water tensions in Central Asia.” Eurasia Review. September 15, 2014.

Dominguez, Gabriel. 2014. “Central Asia’s intensifying water dispute(link is external)” Deutche Welle. September 12, 2014.

38 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2014. “World Urbanization Prospects 2014 Revision.(link is external)”

Economist. 2015. “Bright lights, big cities(link is external).” February 4, 2015.

39 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2014. “World Urbanization Prospects 2014 Revision(link is external).”

Engelke, Peter. 2013. “Foreign policy for an urban world: Global Governance and the Rise of Cities(link is external),” Strategic Foresight Initiative, Atlantic Council.

40 Examples include the Asian Network of Major Cities 21(link is external) and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group(link is external)(link is external)

41 Khanna, Parag. 2014. “Nations are no Longer Driving Globalization – Cities Are(link is external),” Quartz. January 9, 2014.

42 McCurry, Justin. “Tokyo’s rightwing governor plans to buy disputed Senkaku Islands(link is external),” The Guardian (2012).

43 Low, Donald. 2014. “The End of the Singapore Consensus(link is external),” Vox.

44 Jakobson, Linda and Seong-Hyon Lee. 2013. “The North East Asian state’s interests in the Arctic and possible cooperation with the Kingdom of Denmark.(link is external)” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. April 2013.

Wilson, Page. 2014. “Asia eyes the Arctic(link is external)” The Diplomat. August 26, 2013.

Lackenbauer, Whitney. 2014. “Canada and the Asian observers to the Arctic Council: Anxiety and opportunity(link is external).” Asia Policy 18. July 2014.

45Rudner, Martin. 2012. Assessing Cyber Threats to Canadian Infrastructure(link is external). Report prepared for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

46 Clarke, Richard A. 2010. Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What Do About it. New York: Harper Collins.

47 Jervey, Ben. 2014. “Exporting the Colorado River to Asia, through hay.(link is external)” National Geographic. January 24, 2014.

48 Royal Geographic Society. 2014. “What is virtual water?(link is external)” 21st Century Challenges.

Virtual Water. 2004. “Virtual Water – Water for our Future(link is external). August 19, 2004.”

49 Hampson, Fen Osler and Derek H. Burney, Brave New Canada: Meeting the Challenge of a Changing World (2014). McGill-Queen’s University Press: Montreal.

50 “Edward John: Why BC’s First Nations need a China Strategy(link is external).” Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada video. August 9, 2014.

51 The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. “Canadian-Asia Relations: Now for the hard part(link is external).” Speech delivered by Yuen Pau Woo to the Canadian Club of Toronto. June 2014.