Economy Cluster Findings – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

PDF: Economy Cluster Findings – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

On this page

Introduction

Summary of Key Economic Changes in Asia (Insights) and Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

Key Changes in Asia (Insights)

Policy Challenges and Opportunities for Canada

- A new economic centre

- Digital infrastructure 3.0

- Canada’s disrupted labour market

- Taxation pressures

- Trade dilemmas

- Policy lever pressures

Note to the reader

This Economics Cluster Foresight Study explores key changes in Asia and related policy challenges and opportunities for Canada. The key changes are in the form of “insights”, which identify existing and emerging developments that may significantly alter the system under study. Insights help build our understanding of how an issue or system may evolve and what the consequences might be. A policy challenge or opportunity is an issue that current policies or institutions may not be ready or able to address. Identifying, analyzing, debating and clarifying challenges or opportunities help policy makers develop more robust strategies.

Part of the Horizons Foresight Method also involves the exploration of plausible scenarios and the identification of robust assumptions. These are included in the MetaScan on “The Future of Asia” which integrates the high level insights and policy challenges and opportunities from all four cluster studies (economic, energy, geostrategic, social).

The key changes and potential policy challenges and opportunities explored in this study are intended to be provocative in order to stimulate thinking among public servants about the future. They do not reflect a view of the most likely shape of change in Asia or consequences for Canada, but rather plausible developments that merit consideration. While this study’s development involved participation and contributions from officials across multiple departments within the federal public service of Canada, the contents of the study do not necessarily reflect the individual views of participants or of their respective organizations.

Introduction

For most of human history, Asia was the center of the global economy. In the next 10-15 years, Asia will likely reclaim this distinction from the West. Over the same period, it is anticipated that technological innovations such as cheap virtual telepresence, artificial intelligence (AI), robotics and additive manufacturing will begin to strongly affect domestic and international economies. Concurrently, socio-economic changes driven by the sharing economy, growing use of digital services and the increased use of freelancing will dramatically change the nature of work. The interaction and interplay between these co-occuring forces of change – a rising Asia, the collaboration economy and an emerging digital economy – will have widespread impacts on global economic institutions and markets. Existing notions about the centrality of the U.S. to the global economic order, the autonomy and independence of Canada’s service economy and the viability of revenues for government operations may have to be modified or rejected.

The following table summarizes the key economic changes (insights) that are shaping Asia and the potential policy challenges and opportunities for Canada addressed in this study.

Summary of Key Economic Changes in Asia (Insights) and Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

Policy Challenges & Opportunities for Canada

1. A new economic centre

As Asia becomes the world’s new economic center of gravity, Canada will need to further shift focus from trade with the U.S. to take advantage of growth in Asia.

2. Data infrastructure 3.0

Canada will need to prepare itself to ride the next generation of digital infrastructure that will be the highways and railways of the 21st century.

3. Canada’s disrupted labour market

The impacts of technology (automation, 3D printing and AI), the unbundling of work and the emerging virtual service economy combine as a triple-threat to Canada’s labour market.

4. Taxation pressures

The capacity of governments to redistribute wealth under the current taxation model is limited when confronting a disrupted labour market and the sharing economy.

5. Trade dilemmas

Canada faces new challenges on the trade front as trade in services and digital trade of goods and services deepen their contribution to the economy.

6. Policy lever pressures

Government has traditionally had specific policy levers at its disposal, but this may be challenged by limitations driven by structural changes to the economy.

Key Economic Changes in Asia (Insights)

Asia is rising

- Rise of the Asian giants: In 2030, Asia will house three of the world’s four largest economies. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #1)

- New emerging consumer class: By 2030, Asia will have more consumers than the rest of the world combined. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #1)

- Asian economic leadership: Asian businesses may determine the shape of global economics – drive innovations and set standards – with different rules and conventions than the West. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #1)

The new digital economy

- Digital infrastructure 3.0: Massive and growing investments in digital infrastructure are positioning Asia to capitalize on growing technological trends and in so doing, dominate the global digital economy. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #2)

- Job unbundling: Job unbundling will drastically reshape the global service economies, and will hasten the convergence of global wage rates to the advantage of Asia. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #3 & 4)

- Rise of Asian virtual services: As the Asian manufacturing sector evolves, surging Asian participation in the global service sector may dramatically re-shape the provision of virtual services. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #2, 3 & 4)

The collaborative economy

- Ownership unbundling: The rise of the collaborative economy and ownership unbundling in Asia may significantly disrupt established government regulations, taxation, and traditional business models. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #4)

- IP, frugal innovation and trade: The rejection of customary western intellectual property agreements in Asia and the widespread adoption of frugal innovation may combine to threaten existing trade agreements, intellectual property laws, institutions and traditional high margin industries. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #5)

- Economic challenges: The rapid adoption of new digital technologies in Asia and the emergence of a digital economy could lead to extended periods of economic disruption and possibly deflation. (links to policy challenge and opportunities #4 & 6)

Key Changes in Asia (Insights)

Asia is rising

By 2030, Asia could be the world’s new economic center of gravity. With some of the world’s largest economies, an emerging digitally connected consumer class and world-leading corporations innovating to meet their needs, the rise of Asia could reorient markets and reshape the very nature of the global economy.

Rise of the Asian giants

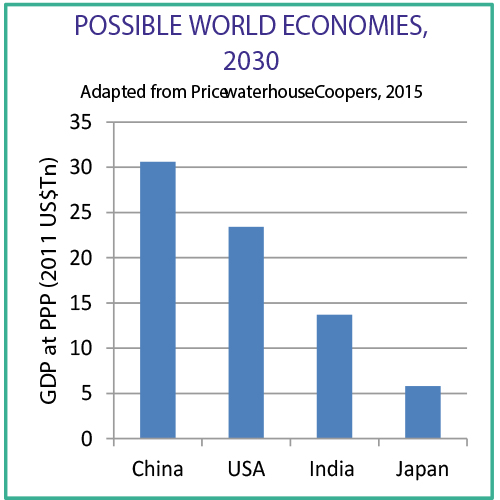

In 2030, Asia will house three of the world’s four largest economies. China’s GDP exceeded that of the U.S. in 20141 by purchasing-power parity (PPP), and it is projected to surpass the U.S.2 using official exchange rates around 2021. India’s economy has the potential to grow at an even faster pace, reaching 2/3 the size of the U.S. by 20303 (see Figure 1) and potentially surpassing China by 2050.4. With fast-growing countries such as Indonesia5 and the Philippines6, the ASEAN economies combined will likely be almost half the size of China or India.

Figure 1 – Possible World Economies

This figure is a bar chart which illustrates possible world economies in 2030. The x-axis displays 4 countries from left to right – China; USA; India; Japan, while the y-axis displays GDP at purchasing-power parity in 2011 in US trillion of dollars. China’s GDP exceeded that of the U.S. in 2014 by purchasing-power parity (PPP), and it is projected to surpass the U.S. using official exchange rates around 2021. India’s economy has the potential to grow at an even faster pace, reaching 2/3 the size of the U.S. by 2030.

New emerging consumer class

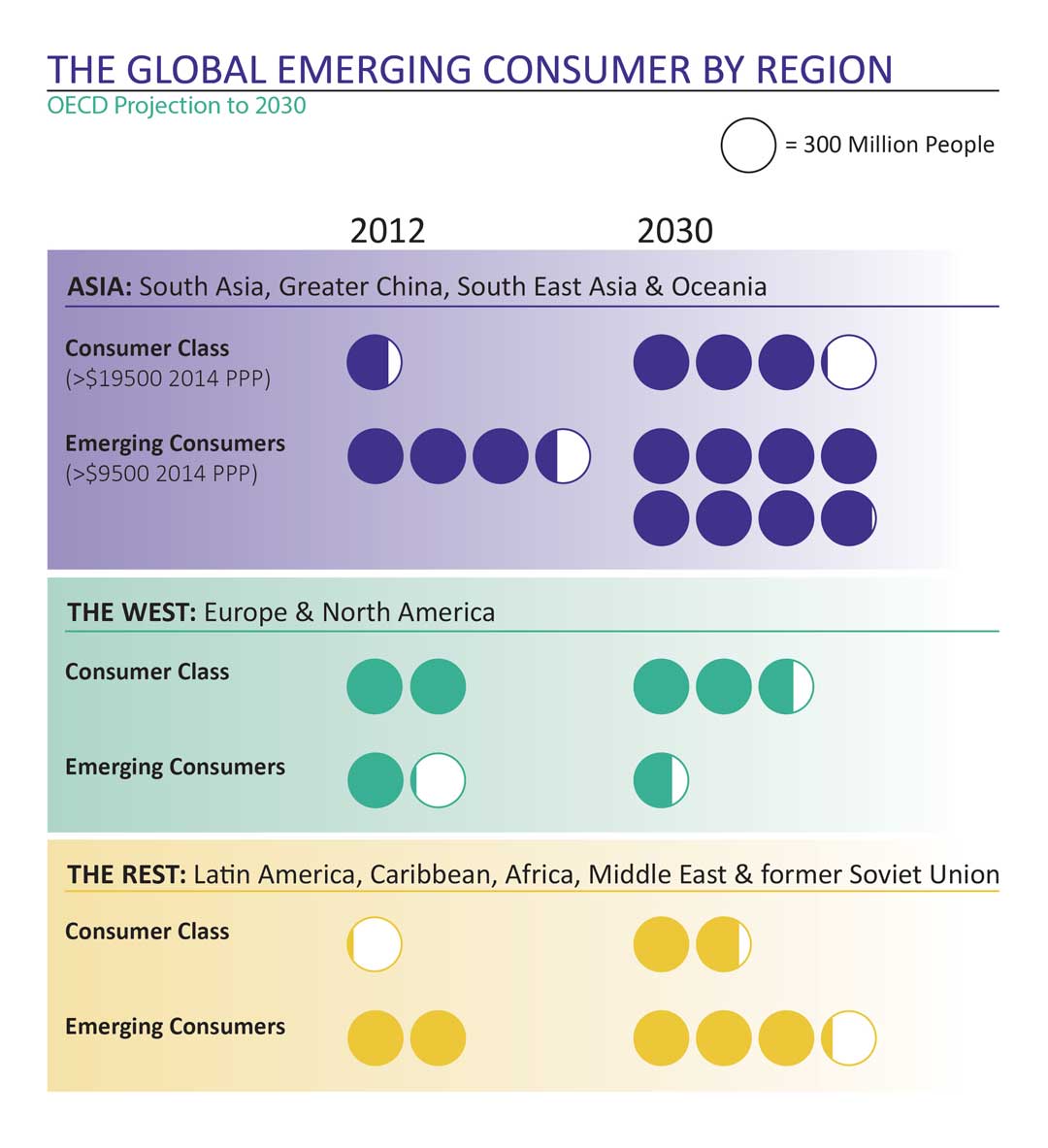

By 2030, Asia will have more consumers than the rest of the world combined. Asia’s share of global consumers (defined as those with incomes over $19,500 per year by PPP) will be larger than the West’s by 2030. Combined with Asia’s 2.4 billion emerging consumers (with incomes larger than $9,500 by PPP) the overall number of consumers in Asia by 2030 will surpass both the West and rest combined (see Figure 2). Equipped with the tools and connectivity to participate in the global economy they will play an increasing role in shaping global consumption patterns and tastes. Emerging consumers in particular will create significant demand for affordable products, requiring frugal innovation.

Figure 2 – The Global Emerging Consumer by Region

This figure is entitled “Population by wealth category, 2012 and 2030” and illustrates the global emerging consumer by region. The chart breakdowns the transition between the growth in consumer class and emerging consumers between 2013 and 2030 in the following three regions: Asia (South Asia, Greater China, South East Asia & Oceania); the West (Europe & North America); and the Rest (Latin America, Caribbean, Africa, Middle East & former Soviet Union). In summary, by 2030, Asia will have more consumers than the rest of the world combined.

Asian economic leadership

Asian businesses may determine the shape of global economics – drive innovations and set standards – with different rules and conventions than the West. Large numbers of Asian firms are entering the global marketplace, and evidence of this rise can be seen from the Forbes Global 2000 list, ranking the world’s largest publicly-listed companies. Last year, Asia surpassed North America for the first time, with 674 companies to 629.7 While the Chinese economy is currently advancing at a slower pace than has been seen recently, China and India may eventually be considered the “heartland of the global economy(link is external),8 and expectations are that even in advanced markets such as the U.S., it is only a matter of time before industry leaders such as Ali Baba, Baidu, Tencent or Xiaomi9 demonstrate they are not just imitators or masters of incremental improvement, but technical leaders working at the cutting edge of research and innovation.10

The new digital economy

The emergence of new technologies, building on the foundation of the digital communications infrastructure, will profoundly reshape the nature of work and commerce.

Digital infrastructure 3.0

Massive and growing investments in digital infrastructure are positioning Asia to capitalize on growing technological trends and in so doing, dominate the global digital economy. While Canada ranks 8th internationally on the Mastercard Digital Evolution Index(link is external), its score is essentially unchanged in the past five years while almost every major Asian nation has made significant digital advances. Active state intervention in key Asian countries such as China and South Korea11 has led to rapid adoption of more advanced data infrastructure than in many parts of the West that rely on private providers. Asian nations are leap-frogging existing technologies, building a faster, cheaper digital infrastructure. For example, South Korea’s Internet connections average speeds 2.5 times faster than those in the Canada for ¼ the price.12

These digital infrastructure investments will allow Asia to capitalize on many of the technological trends that will shape the global economy over the next several decades. While Taiwanese electronics assembler Foxconn’s plans to replace workers with one million robots by 2014 have yet to be realized – they indicate the scale of the ambition for future automation.13 China is the world’s largest robot market with a 20% share of the global total,14 and they expect to double their existing 30 industrial robot factories by 2017,15 with investments subsidized and encouraged by local governments.16 As industrial processes continue to automate through next-gen robotics and the deployment of evolving technologies such as 3D printing, the number of manufacturing jobs in the future is expected to decline significantly both in Asia and in the West.

The challenge presented by artificial intelligence (AI) and the continued development of the Internet of Things represents a major disruption for the service sector. AI can already provide seamless English to Spanish voice-to-voice translation17; recognize faces and emotions18; objects19; write songs20 and sports articles21; learn relationships between entities22; optimize designs better than humans23; and provide personal assistance.24 Meanwhile, the Internet of Things25 is breaking new ground in integrating dramatic advances in sensors, video, location information, networking and cloud computing to provide new capabilities. Over the next 15 years, AI and sensor networks will be seamlessly fused and incorporated into business processes as basic tools of the trade with Asian Pacific spending forecasted to reach $58 billion by 2020.26 It is predicted that new corporate applications of web technologies could represent up to 22% of China’s productivity growth by 2025, potentially increasing China’s GDP by up to $240 billion.27 Combined with the impacts of automation and 3D printing, Asia is well positioned to capitalize on these trends and disrupt the current economic paradigm.

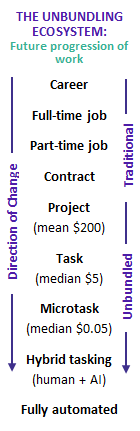

Job unbundling

Job unbundling will drastically reshape the global service economies, and will hasten the convergence of global wage rates to the advantage of Asia. The first stage of job unbundling is well established in the workplace (career and full-time work shifting to part-time or contracts). Globally over the next 15 years, jobs and contracts themselves will be unbundled into a freelance, project-based economy, serviced by companies such as eLance.com(link is external), or even down to a task-oriented economy, where services such as Fiverr.com(link is external) and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk(link is external)deconstruct tasks to as low as $5 or even $0.05 (see Figure 3). Asia is already a leader in unbundled services, with Asian nations holding five of the top ten28 positions on eLance’s top freelancing countries list. This market is projected to be a $5 billion industry in 201529 and for some nations (such as the U.S.) freelance work may represent 50% of the fulltime workforce as early as 202030. Given that Asia currently has a significant wage-rate advantage over the West31, a global move down the unbundling curve will favour Asian workers and will likely trigger a convergence of global wage rates.

Figure 3 – The Unbundling Ecosystem

This figure is entitled “The unbundling ecosystem: future progression of work” shows a direction of change from more traditional work to unbundled work. The list moves from traditional to unbundled. Starting from the top and moving downwards we have: career; full-time job, part-time job; contract; project (mean $200); task (median $5); microtask (median $0.05); hybrid tasking (human + AI) and fully automated.

Future fictional vignette – “North American Information Technology Federation”. Wikipedia. July 8, 2029. Web. Accessed May 4, 2030.

Summary

The North American Information Technology Federation (NAITF) was launched in 2026 when the impacts of strong competition from both India and China drove down the cost of high-end IT services across western markets. The 2020’s had already seen Microsoft’s Cortana for Business and Google’s Now+ effectively decimate the majority of customer service and tech support positions worldwide through scalable AI. Recognizing the inevitable, Asian IT outsourcing firms were already leveraging growing Asian education levels to move up the service value chain. Competition was fierce and with wages plunging and domestic unemployment rising quickly, NAITF found a surge of new members from the ranks of North American programmers, engineers, data scientists and security analysts. Flush with funds and a vocal membership, NAITF successfully lobbied for laws in both Canada and the US mandating minimum education levels and rigorous background checks, ostensibly to ensure data security. The response was swift. U.S. military sales to India plunged the following year while Canadian pork and potash sales to China nearly ceased. Further, Canada’s attempt to join the Pan-Asian advisory board on harmonized telemedicine standards was summarily rejected. This triggered a three year economic conflict referred to colloquially by the media as the ‘Service Trade Wars.’

See also

Rise of Asian virtual services

As the Asian manufacturing sector is forced to evolve, surging Asian participation in the global service sector may dramatically re-shape the provision of virtual services. Traditionally, low cost manufacturing was a required pathway for economic growth in Asia32 because it facilitated the movement of poor agrarian labourers to middle-class, urban jobs. However, in the context of declining centralized Asian manufacturing, driven by growing automation and 3D printing, success in the service industries must be explored as an alternative path to growing employment and rising incomes in Asia.33 The current Indian service economy represents 62.5% of GDP,34 while Hong Kong’s economy is 90% service based35 demonstrating this approach is feasible, even using the limited digital technologies of the early 21st century. Fortunately, evolving digital tools such as telepresence technologies36 and augmented reality, combined with the trend towards job unbundling, will greatly assist this transition. Despite their economic growth, almost 50% of China’s37 and more than 50% of India’s38 workforces remain agrarian based. As these and smaller developing economies further grow and urbanize, they will need to compete successfully in the global market for services, that in future will range from simple web searches up to traditional white collar work such as programming, engineering, accounting39 and even the provision of complex health services.40

The collaborative economy

The nature of capitalism may be changing. Businesses will continue to develop new ideas and commerce will continue to drive the global economy. However, what is sold, to whom and by what means may be changing as new consumption mechanisms and evolving values emerge.

Ownership unbundling

The rise of the collaborative economy and ownership unbundling in Asia may significantly disrupt established government regulations, taxation, and traditional business profit models. Ownership unbundling reflects two significant forces impacting traditional ownership models – the sharing or collaborative economy and the open source movement. While Asian economies are rooted in a history of barter exchange, the Sharing Economy41 has quickly evolved, facilitated by social media and is growing in Asia and worldwide, an example of which is the recent $18M U.S. investment in Korean ride sharing service Socar.42 Increasingly, people are willing to trade resources directly with others, so much so that the revenue gained by consumers sharing personal assets is expected to have surpassed $3.5 billion in 2014, with annual growth exceeding 25%.43

This trend overlaps in many ways with the growing power of open source software where traditionally a single author develops software code that is shared freely; it gets used and modified with the updated version freely shared as well. The market disruption potential is well established – versions of Linux have displaced Microsoft Windows on 67.2% of the world’s web servers,44 while Android now controls 84.4% of smartphones45; these numbers are higher in Asia. Napster, transformed the music industry to a largely digital model with low/no profit margins while more recently, BitTorrent has extended this concept to video and software and itself is now facing competition in Asia from Xunlei.46 In the next 15 years, ownership unbundling will expand into new areas, for instance through the sharing, sale and production of 3D printing templates(link is external) through synthetic biology forums such as the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition,47 a worldwide challenge to build simple biological systems from standard, interchangeable parts called Biobricks.48 In 2014, 82 Asian teams competed49 (representing 1/3 of the competitors). These forces serve to disrupt traditional business models, often moving faster than government regulation, taxation policies or existing business models can react.

Intellectual property, frugal innovation and trade

The rejection of customary western intellectual property agreements in Asia and the widespread adoption of frugal innovation may combine to threaten existing trade agreements, intellectual property laws, institutions and traditional high margin industries. The current western framework for intellectual property (IP) may not be appropriate or appealing for Asian nations.50 Current western trade policy focuses on securing investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms and further strengthening IP protection. However, these elements may be rejected by large Asian powers as demonstrated by India and China’s defense of domestic production of generic drugs51 at the World Trade Organization and India’s Supreme Court’s rejection of the Novartis patent on Gleevec.52 Compounding this trend, trade between Asian countries has grown rapidly over the past ten years, due in part to an expanding medley of crosscutting bilateral trade agreements between states that may further weaken interest in IP restricting agreements with the West.

Frugal Innovation

As Asian economies continue to evolve, consumer demand will drive companies to increasingly adopt frugal innovation processes (see box).53 While technology leaders Apple and Samsung have fought globally over the high end of the smart phone market, new competitors have emerged to grab market share in developing Asia. Utilizing frugal methods, China’s Xiaomi has emerged as a dominant smartphone vendor in both India and China54 while India has launched multiple home-grown frugal smartphone vendors of its own. These Indian competitors are making inroads in the low cost local market, but like Xiaomi, have aspirations for global distribution.55 These companies are seizing market share by concentrating on overlooked consumers56 such as the emerging consumer class, where firms expect volume will offset razor-thin profit margins.57 If firms choose to pursue a frugal development path, this will impact all levels of society as many of the products will be equally appealing to traditional middle class consumers both in Asia and the West, potentially disrupting many traditional industries and business models. This may present another driver to resist Western pressure for strong IP protection in trade deals, as Asian nations may prefer the innovation and affordability benefits that come from a low IP, low margin environment.

Finally, as the digitization of the global economy allows services traded through digital global value-chains to bypass state monitoring and control, many forms of state intervention in the economy will become more difficult to implement and increasingly irrelevant, including trade and investment controls, taxation, regulation, anti-trust and privacy protections, resulting in a de facto condition of trade liberalization.

Frugal innovation: As a process discovers new business models, reconfigures value chains, and redesigns products to serve users who face extreme affordability constraints, in a scalable and sustainable manner. It involves either overcoming or tapping institutional voids and resource constraints to create more inclusive markets. See video: Rise of the Frugal Economy.(link is external)(link is external)

India’s Tata Motors makes the Nano car, retailing at about $3,000 USD.

The Aakash tablet created for the Indian market currently sells for as low as $55 USD.

Economic challenges

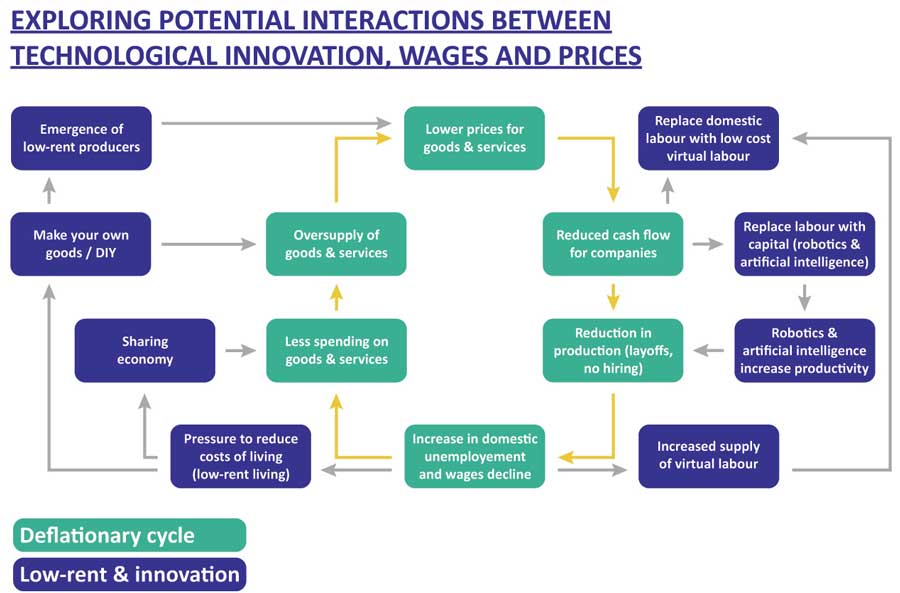

The rapid adoption of new digital technologies in Asia and the emergence of a digital economy could lead to extended periods of economic disruption and possibly deflation.

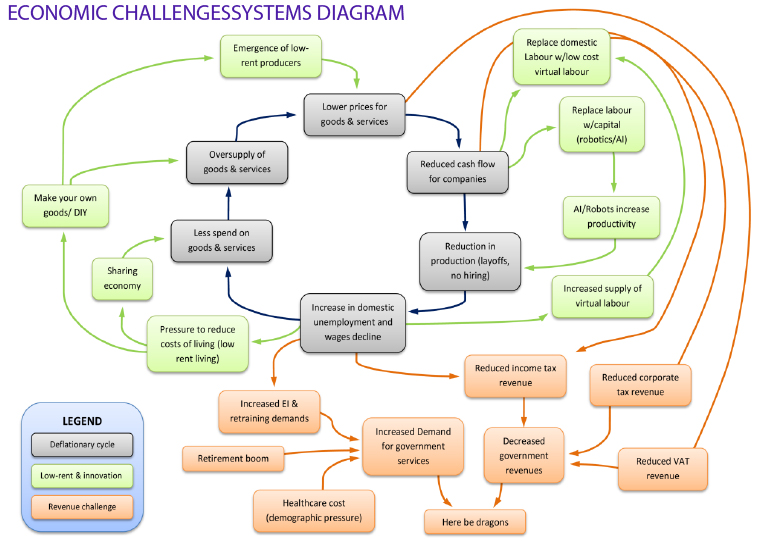

Several factors could contribute to economic decline and deflationary pressures in Asia, including the accelerated continental rise as an economic power at the same time as a rapid transition to a digital economy, increasingly unbundled ownership, the impacts of AI, automation and work unbundling and more low IP/low margin climates. While lower prices may sound appealing to consumers and may partially offset some of the other negative economic events, it is a mounting concern for Asian economists that factory gate prices are falling. Some 82% of the items in the producer price basket are deflating in China, 90% in Thailand, and 97% in Singapore.58 Sustained deflation disrupts the workings of an economy built on the assumption of continued growth, and can result in a number of self-reinforcing feedback loops that could result in a recessionary spiral of decreasing demand and employment. The extent and duration of a possible period of decline would likely be uneven, both globally and within Asia which may further amplify existing inequalities within the global economic community.

Figure 4 – Exploring Potential Interactions Between Technological Innovation, Wages and Prices

Figure 4 explores the potential interactions between technological innovation, wages and prices. This image is a system map consisting of green and purple text boxes of various elements which show the relationships among them. The legend at the bottom of the image assigns the green text boxes to deflationary cycle, while the purple boxes represent low-profit & innovation. The system map starts in the centre with the deflationary cycle and moves in a clockwise direction with the following 6 elements: 1) lower prices for goods & services; 2) reduced cash flow for companies; 3) reduction in production (layoffs, no hiring); 4) increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline; 5) less spending on goods and services; and 6) oversupply of good & services. All of these elements are linked in a clockwise direction with a yellow arrow. The outer part of the system map is made up with the following 8 low-profit and innovation elements: 1) emergence of low-profit producers; 2) replace domestic labour with low cost virtual labour; 3) replace labour with capital (robotics & artificial intelligence); 4) robotics & artificial intelligence increase productivity; 5) increased supply of virtual labour; 6) pressure to reduce costs of living (low-profit living); 6) sharing economy; 7) make your own goods/DIY; and 8) emergence of low-profit producers. Increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline links to pressure to reduce costs of living (low-profit living) which links to sharing economy, make your own goods/DIY and emergence of low-profit producers links to lower prices for goods & services. Increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline also links to increased supply of virtual labour which links to replace domestic labour with low cost virtual labour. Replace labour with capital links to robotics and artificial intelligence links to reduction in production. Reduced cash flow for companies links to replace domestic labour with low cost virtual work and replace labour with capital.

Policy Challenges and Opportunities for Canada

The rapid changes that may occur in Asia over the next 10-15 years will present Canada with a range of challenges and opportunities. This section highlights those that may be particularly surprising and unexpected.

A new economic centre

As Asia becomes the world’s new economic center of gravity, Canada will need to further shift its focus from trade with the U.S. to take advantage of growth in Asia. Trade in goods and resources may be mostly about opening markets, but the more lucrative potential of trade in services59 may require significant reframing and internal change in engagement, mindset, and partnerships. Second, the world economy will increasingly be dominated by rising Asian powers. As Asia continues to grow, Canada will find itself in a new world where, as for most of recorded history, Asia is central. Canada, along with other countries, will need to increase focus to Asian partners,60 paying greater attention to Asian consumers and particularly those in a fast-rising India, or alternatively, use existing partnerships to engage indirectly with Asia. This will have wide-ranging impacts on international institutions, the economic balance of power, and firm and state relationships.

Digital infrastructure 3.0

Canada will need to prepare itself to ride the next generation of digital infrastructure that will be the highways of the 21st century. Canada, in 2014, confronts broadband pricing and speed that is middle of the pack internationally. This represents a major challenge as broadband and wireless are set to become the utilities upon which all future commerce is conducted, particularly telepresence. However, digital infrastructure extends beyond simply ensuring fast and inexpensive access. The Internet of Things and pervasive sensor networks with the corresponding flood of public and private information will radically change how consumers, businesses and governments interact while re-defining our current concepts of Big Data. The development and growth of this new digital infrastructure will be critical to ensuring the security and privacy of online transactions, and will support the provision of government services within Canada itself. While Canada’s market-based approach to digital infrastructure has managed the first digital transition reasonably well, it contrasts with the government-supported approach adopted in many Asian nations and may not be sufficient to meet Canada’s growing infrastructure needs if it wishes to effectively compete in the growing global digital market.

Canada’s disrupted labour market

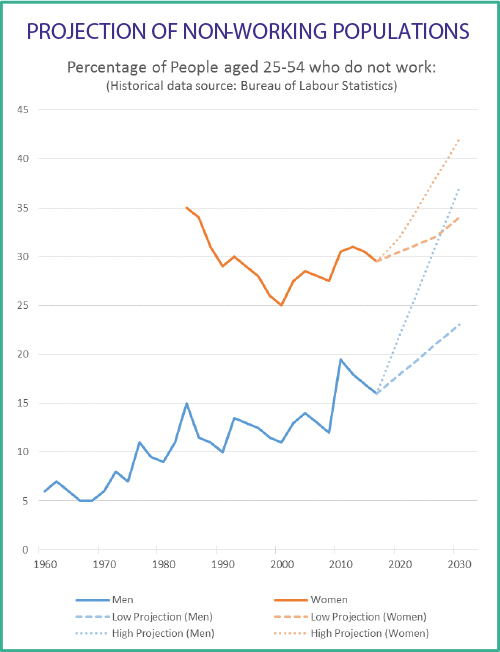

The impacts of technology (automation, 3D printing and AI), the unbundling of work and the emerging virtual service economy combine as a triple-threat to Canada’s labour market. The growth of automation and 3D printing may provide an opportunity for the reshoring of manufacturing to Canada. However, these technologies generally require few employees compared to traditional manufacturing and may serve to further disrupt other existing manufacturing employment in Canada. The combination of AI and the rise of Asian virtual services will allow for further encroaching on the West’s white-collar professions or licensed trades and may also open opportunities to provide advice and oversight via telepresence in areas that in the past have not traditionally been offshored (i.e. healthcare). Finally, the unbundling of work may not be solely an Asian phenomenon. While the price point of projects and tasks may not be initially appealing to Canadian workers, the volume of work available and a growing number of unemployed Canadian workers may eventually draw them into the unbundled employment world. These forces may combine to push the percentage of Canadian’s not working or those under-employed or comparatively underpaid to new highs, resulting in stresses on existing social, employment and pension programs. The accompanying graphic (see Figure 5) drawing from U.S. figures, documents the steady rise in the percentage of the population not working and extrapolates high and low projections to 2030.

Figure 5 – Projection of Non-Working Populations

This is a line graph is entitled “Projection of non-working populations” and has a subtitle of “Percentage of People aged 25-54 who do not work: Historical data source: Bureau of Labour Statistics). It depicts the steady rise in the percentage of the population not working and extrapolates high and low projections to 2030. The x-axis represents the percentage and ranges from 0% to 45% in intervals of 5. The men are represented by a blue line and the women are represented by a red line. The low projection for men between 2020 and 2030 is projected to increase from 16% to 27%, which is represented by a blue dashed line. The high projection for men between 2020 and 2030 is projected to increase from 16% to 37%, which is represented by a blue dotted line. The low projection for women between 2020 and 2030 is projected to increase from 30% to 34%, which is represented by a red dashed line. The high projection for women between 2020 and 2030 is projected to increase from 30% to 43%, which is represented by a red dotted line.

Taxation pressures

The capacity of governments to redistribute wealth under the current taxation model may be limited when confronting a disrupted labour market and the sharing economy. There are three distinct threats to Canada’s traditional taxation approaches. The growth of AI, automation and the rise of Asia’s virtual digital services serve to eliminate or replace Canadian jobs, with a corresponding direct reduction in Canadian taxable incomes. Conversely, work unbundling and the sharing economy may create new employment opportunities, but these will either pay less than a comparable full-time position, or be much more difficult (if not impossible) to track and tax. Further complicating the taxation picture is the mobility provided by new digital technologies. The concept of “place” will increasingly matter less for commerce as the use of remote data centres, teleconferencing and AI will allow for operations to be conducted anywhere while servicing customers everywhere. This will allow Canadian corporate operations the flexibility to relocate when confronted by restrictive regulations or in the face of aggressive corporate taxation.

Trade dilemmas

As Asia and the world increasingly shifts towards digital trade, traditional trade policy approaches may no longer be effective. A whole new world of trade in digital goods and services is emerging and growing fast. McKinsey estimates that global online traffic across borders could increase eightfold by 2025, 61 with Asia leading the way.62 The potential impact of this digitization of trade is only beginning to emerge. For large corporations, digital trade increases efficiency, lowers operating costs, and facilitates tax optimization strategies. But perhaps the most dramatic change is for individual entrepreneurs and small- and medium-size firms, for whom digital trade can unlock huge new global markets. “Internet platforms are empowering these ‘micro-multinationals,’ enabling them to find customers, suppliers, funding, and talent around the world at lower cost. Digital platforms can cut the cost of exporting by 83% as compared with traditional export channels”.63 Digital trade in goods and services is likely to expand and co-evolve with the development of artificial intelligence, data analytics, sensors and the Internet of Things, and international digital services are likely to penetrate deeply into our lives and homes. In sum, the world is entering an era of enormous opportunity and intense competition. For governments the challenges are how to monitor regulate and enforce standards in areas such as finance, labour, health and safety in a rapidly evolving digital economy. Traditional trade protections and trade liberalization agreements may become less relevant as a greater percentage of global trade is able to bypass state monitoring and control. Investment controls, taxation, regulation, anti-trust and privacy protections may also be affected. Canada has been successful in building ports and eliminating tariffs to prosper in the old trade regime, but may need to give more thought to preparing for the emerging era of digital trade.64

Policy lever pressures

Government has traditionally had specific policy levers at its disposal, but this may be challenged by limitations driven by structural changes to the economy. The taxation pressures, described above, would limit government capacity for spending at the same time as demand would be increasing. Government services and assistance would be ever more sought after due to, among other things, higher unemployment, restructuring of entire economic sectors, periods of deflation, an aging population, and subsequently higher health care costs. A growing segment of society, increasingly disaffected and disadvantaged, would be seeking assistance from governments that would have fewer tools to help achieve its objectives. Figure 6 depicts this relationship and the convergence of increased demand for government services with decreased government revenues; however, two key elements cannot be demonstrated: the speed and scale of how these effects could transpire. Consequently, governments may be afforded the opportunity to seek new methods to help achieve societal objectives.

Figure 6 – System map of economic challenges

This is a system map of economic challenges. It contains elements from the following three areas: 1) deflationary cycle; 2) low-rent & innovation; and 3) revenue challenge. The following elements part of the deflationary cycle are: lower prices for goods and services; reduced cash flow for companies; reduction in production (layoffs, no hiring); increase in domestic unemployment and wages decline; less spend on goods and services and oversupply of goods & services. The following elements are part of low-rent & innovation: emergence of low-rent producers; replace domestic labour with low cost virtual labour; replace labour with capital (robotics/AI); AI/Robots increase productivity; increased supply of virtual labour; pressure to reduce costs of living (low rent living); sharing economy and make your own goods/DIY. The following elements are part of the revenue challenges: increased EI & retraining demands; reduced income tax revenue; reduced corporate tax revenue; reduced VAT revenue; decreased government revenues; increased demand for government services; here be dragons; healthcare cost (demographic pressure); retirement boom. In summary, a growing segment of society, increasingly disaffected and disadvantaged, would be seeking assistance from governments that would have fewer tools to help achieve its objectives. This figure depicts this relationship and the convergence of increased demand for government services with decreased government revenues; however, two key elements cannot be demonstrated: the speed and scale of how these effects could transpire.

Notes

1 Bird, M. 2014. China Just Overtook The US As The World’s Largest Economy. http://www.businessinsider.com/china-overtakes-us-as-worlds-largest-economy-2014-10(link is external)(link is external). Accessed Feb 17, 2015.

2 The Economist. 2014. Catching the Eagle. http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2014/08/chinese-and-american-gdp-forecasts(link is external)(link is external).

3 PwC Economics. 2013. World in 2050 The BRICs and beyond: prospects , challenges and opportunities.http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/the-economy/the-world-in-2050.jhtml(link is external)(link is external)

4 Citi Private Bank. 2012. The Wealth Report 2012. https://www.privatebank.citibank.com/pdf/wealthReport2012_lowRes.pdf(link is external)(link is external)

5 McKinsey Global Institute. 2012. The archipelago economy: Unleashing Indonesia’s potential. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/asia-pacific/the_archipelago_economy(link is external)(link is external)

6 AG Reporter, Arabian Gazette. 2014. Philippines to become trillion dollar economy by 2030.http://www.pacifichub.net/news-articles/philippines-to-become-trillion-dollar-economy-by-2030(link is external)(link is external).

8https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3WjLdDaDqU(link is external)(link is external)

9 Pilling, D. 2015. Corporate China not yet ready to rule the world. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/6a89acf6-ac58-11e4-9d32-00144feab7de.html#axzz3RSaYfuUw(link is external)(link is external).

10 Ong, Y. 2014. The Ten Most Innovative Companies in Asia 2014.http://www.forbes.com/sites/yunitaong/2014/08/20/the-most-innovative-companies-in-asia-2014/(link is external)(link is external).

11 Neal, M. 2014. South Korea’s Internet Is About to Be 50 Times Faster Than Yours.http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/south-koreas-internet-is-about-to-be-50-times-faster-than-yours(link is external)(link is external).

12 OECD. 2014. OECD Broadband Portal. http://www.oecd.org/internet/broadband/oecdbroadbandportal.htm(link is external)(link is external)

13 MacRumours. 2014. Foxconn Robots Proving Unsuitable for iPhone Assembly, Updated Versions in the Works.http://www.macrumors.com/2014/12/05/foxconn-robots-iphone-assembly/(link is external)(link is external)

14 Bastian Robotics. 2014. Robotics by the Numbers. http://www.bastiansolutions.com/blog/resources/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/robots-by-the-numbers.jpg(link is external)(link is external)

15 Young, A. 2014. China Now Has 30 Industrial Robot Factories, Could Double Robot Population By 2017.http://www.ibtimes.com/china-now-has-30-industrial-robot-factories-could-double-robot-population-2017-1713813(link is external)(link is external)

16 Holcombe, C. 2014. Owners looking at robots to replace workers prone to rioting.http://www.scmp.com/business/economy/article/1519789/owners-looking-robots-replace-workers-prone-rioting(link is external)(link is external)

17 Bright, P. 2014. Skype Translator is the most futuristic thing I’ve ever used. http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2014/12/skype-translator-is-the-most-futuristic-thing-ive-ever-used/(link is external)(link is external)

18 Dormehl, L. 2014. How Machines Learned To Recognize Our Faces So Well—And What’s Next.http://www.fastcolabs.com/3032386/how-machines-learned-to-recognize-our-faces-so-well-and-whats-next(link is external)(link is external)

19 Clark, L. 2012. Google’s Artificial Brain Learns to Find Cat Videos. http://www.wired.com/2012/06/google-x-neural-network/(link is external)(link is external)

20 Hochberg, W. 2014. When Robots Write Songs.http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/08/computers-that-compose/374916/(link is external)(link is external).

21 Hodson, H. 2014. AI knows a great sporting moment when it sees one.http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22429982.000-ai-knows-a-great-sporting-moment-when-it-sees-one.html#.VJQ6tf-DA(link is external)(link is external)

22 Hof, R. 2013. 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2013. http://www.technologyreview.com/featuredstory/513696/deep-learning/(link is external)(link is external)

23 Genetic Programming. 2014. The Annual “Humies” Awards — 2004–2014. http://www.genetic-programming.org/combined.php(link is external)(link is external)

24 Trenholm, R. 2014. Next generation of personal assistant takes a step towards ‘Her’-style super-Siri.http://www.cnet.com/news/next-generation-of-personal-assistant-takes-a-step-towards-her-style-super-siri/(link is external)(link is external)

25 Chui, M. 2010. The Internet of Things.http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/the_internet_of_things(link is external)(link is external)

26 Jeremiah, D et al. 2014. Rapid growth of connected devices expected to drive adoption of Internet of Things (IoT) in Asia Pacific . http://www.frost.com/prod/servlet/press-release.pag?docid=291420110(link is external)(link is external)

27 Woetzel, J. 2014. China’s digital transformation.http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/high_tech_telecoms_internet/chinas_digital_transformation?cid=other-eml-nsl-mip-mck-oth-1408(link is external)(link is external)

28 Elance. 2013. Global Online Employment Report. https://www.elance.com/q/node/1578?mpid=cj_10777892_4003003(link is external)(link is external)

29 Magdirila, P. 2013. Elance records 90% more jobs for Philippine freelancers this year.https://www.techinasia.com/elance-jobs-philippine-freelancers-trust-global-businesses/(link is external)(link is external)

30 Forbes. 2013. How An Exploding Freelance Economy Will Drive Change In 2014.http://www.forbes.com/sites/groupthink/2013/11/25/how-an-exploding-freelance-economy-will-drive-change-in-2014/(link is external)(link is external)

31 Wikipedia. 2015. List of countries by average wage.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_average_wage(link is external)(link is external)

32 Asian Development Bank. 2013. Asia Cannot Bypass Manufacturing on Path to Prosperity – ADB Report.http://www.adb.org/news/asia-cannot-bypass-manufacturing-path-prosperity-adb-report(link is external)(link is external)

33 Park, D and Shin, K. 2012. The Service Sector in Asia: Is It an Engine of Growth?

http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2013/10825.pdf(link is external)(link is external)

34 Altius Directory. 2015. Indian Economy 2015. http://www.altiusdirectory.com/Business/indian-economy.php(link is external)(link is external)

35 Wikipedia. 2015. Economy of Hong Kong. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Hong_Kong(link is external)(link is external)

36 Olson, P. 2013. Rise of The Telepresence Robots. http://www.forbes.com/sites/parmyolson/2013/06/27/rise-of-the-telepresence-robots/(link is external)(link is external)

37 Economy Watch. 2010. China Agriculture.

38 Wikipedia. 2015. Agriculture in India. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agriculture_in_India(link is external)(link is external)

39 Blinder, A. 2007. How Many U.S. Jobs Might Be Offshorable?http://www.princeton.edu/~blinder/papers/07ceps142.pdf(link is external)(link is external)

40 Biesdorf, S and Niedermann, F. 2014. Healthcare’s digital future.http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/health_systems_and_services/healthcares_digital_future(link is external)(link is external)

41 Wikipedia. 2015. Sharing economy. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharing_economy(link is external)(link is external)

42 Tay, D. 2014. “Korean ride sharing service Socar lands massive $18M investment”. https://www.techinasia.com/socar-18m-investment-ride-sharing/(link is external)(link is external)

43 Geron, T. 2013. Airbnb and The Unstoppable Rise Of The Share Economy.http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomiogeron/2013/01/23/airbnb-and-the-unstoppable-rise-of-the-share-economy/(link is external)(link is external)

44 W3 Techs. nd. Usage of operating systems for websites.http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/operating_system/all(link is external)(link is external)

45 IDC. 2015. Smartphone OS Market Share, Q3 2014. http://www.idc.com/prodserv/smartphone-os-market-share.jsp(link is external)(link is external)

46 Wikipedia. 2015. Xunlei. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xunlei(link is external)(link is external)

47 IGEM. nd. Synthetic Biology Based on Standard Parts. http://igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=IGEM/Learn_About(link is external)(link is external)

48 Wikipedia. 2015. BioBrick. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BioBrick(link is external)(link is external)

49 IGEM. 2014. Jamboree Results for iGEM 2014. http://igem.org/Results?year=2014®ion=Asia&division=igem(link is external)(link is external)

50 Endeshaw, A. 2010. Intellectual Property in Asian Emerging Economies.http://www.ashgate.com/isbn/9780754674597(link is external)(link is external)

51 Sen, A. 2012. India, Brazil & China defend generic drugs at WTO. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-06-25/news/32409062_1_counterfeit-medicines-fake-drugs-generic-drugs(link is external)(link is external)

52 Kilday, L. 2013. Global IP Reaction to India’s Rejection of the Novartis Drug Patent.http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2013/05/28/global-ip-reaction-to-indias-rejection-of-the-novartis-drug-patent/id=40778/(link is external)(link is external)

53 Bhatti, Y. 2011. “What is frugal innovation? Definition.” Frugal-Innovation.com. July 25. http://www.frugal-innovation.com/author/yasserbhatti/(link is external)(link is external)

NESTA video, Rise of the Frugal Economy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTZem7lCRww(link is external)(link is external)

Aakash tablet http://www.akashtablet.com/(link is external)(link is external)

54 The Economist. 2015. “The Xiaomi Shock.” http://www.economist.com/news/business/21645217-chinas-booming-smartphone-market-has-spawned-genuine-innovator-xiaomi-shock?frsc=dg%7Ca(link is external)(link is external)

55 The Indian Express. 2014. “Xiaomi now third largest smartphone maker, Indian companies more dominant at home: Canalys.” http://indianexpress.com/article/technology/mobile-tabs/xiaomi-now-no-3-globally-indian-companies-becoming-more-dominant-at-home-canalys/(link is external)(link is external)

56 Fannin, Rebecca. 2013. “Frugal Innovation Evolves in the the Next Phase of China’s Rise as Tech Economy.” Forbes. November 19. http://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccafannin/2013/11/19/frugal-innovation-evolves-in-the-next-phase-of-chinas-rise-as-tech-economy/(link is external)(link is external)

57 Yarrow, J. 2015. “Apple is taking 93% of the profits in the smartphone insustray now.” Business Insider. March 13. http://uk.businessinsider.com/apple-is-taking-93-of-the-profits-in-the-smartphone-industry-now-2015-2(link is external)(link is external)

58 Evans-Pritchard, A. 2014. Spreading deflation across East Asia threatens fresh debt crisis.http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11226558/Spreading-deflation-across-East-Asia-threatens-fresh-debt-crisis.html(link is external)

59 The State Council The People’s Republic of China. 2015. Healthy growth for foreign trade figures(link is external)(link is external).

60 The Governor General of Canada. 2015. Keynote Address at Vancouver Board of Trade — The Next Spike: Innovation as the Key to Building a Smarter, More Caring Canada(link is external)(link is external).

61 Manyika, J., et al., 2014. Global Flows in a Digital Age(link is external)(link is external). McKinsey Global Institute. April.

62 Chen Y., et al. 2015. China’s rising internet wave: wired companies(link is external)(link is external). McKinsey & Company. January.

63 Commerce 3.0 for development: The promise of the Global Empowerment Network, eBay, 2013, ebayinc.com.

64 Goldfarb, D. 2011. Canada’s trade in a digital world(link is external)(link is external). Conference Board of Canada. April.