MetaScan 4 – The Future of Asia: Implications for Canada

Insights about Change in Asia

On this page

Asia’s new emerging consumer class and the rise of frugal innovation

The emerging digital economy in Asia

Ownership unbundling: the collaborative economy and open source

The potential for social disruption

An Asian society in transition could alter global norms and values

Asia’s evolving governance models

Asia could drive innovation in 21st century social policy

The structure of energy demand is changing in Asia

Asia is shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy

Asia’s institutional architecture could alter international relations

The sources of geopolitical conflict could evolve

Asia’s digital dark side

Notes

Insights describe developments that could generate significant disruptive change in one or more of the Asian sub-systems explored in this study: economic, social, energy, and geostrategic. An insight is built by scanning for “weak signals” of a change that, if it were to strengthen, could lead to a significant and surprising divergence from current assumptions about the expected future. Insights are not predictions but rather explorations of plausible high-impact alternatives (or “what ifs”) to be considered in order to develop policies that are more robust across a range of potential future conditions.

Asia’s new emerging consumer class and the rise of frugal innovation

An emerging consumer class of 2.4 billion people in Asia could demand inexpensive products, spur new low-cost business models and lead to the rise of a new generation of Asian corporations that reshape the very nature of the global economy.

Emerging Consumer Class

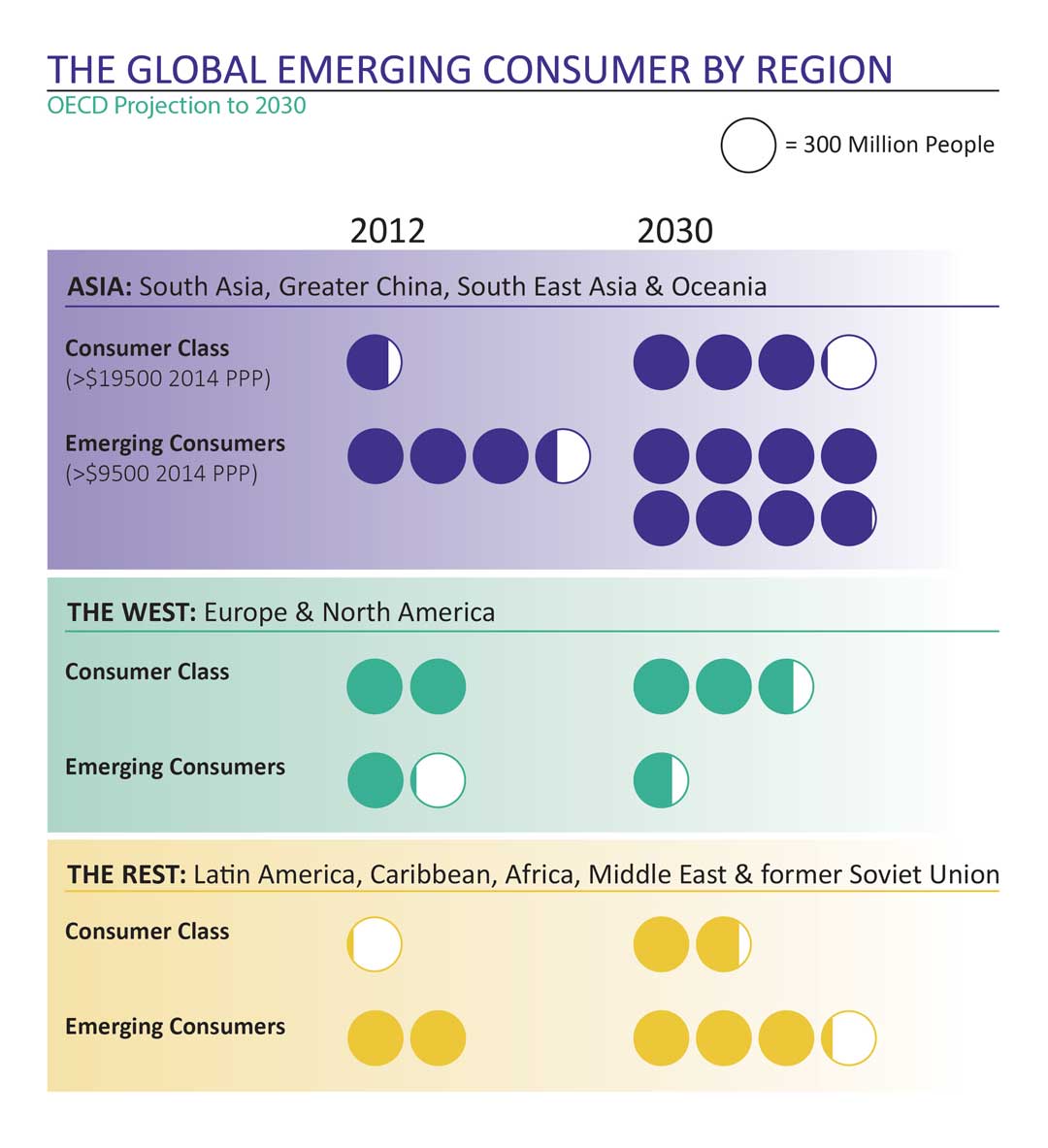

Potentially more significant than the tripling of Asia’s traditional consumer class (i.e. middle class) to one billion people by 2030 could be the rise of 2.4 billion emerging consumers in Asia, with annual incomes between approximately $10,000 and $20,000 (see Figure 1).16 The size of this group, combined with their near universal digital connectivity to e-commerce by 2030, means that their influence will be too significant to ignore and may drive companies to engage in frugal innovation to capitalize on this massive combined consumer market.

Frugal Innovation

As Asian economies continue to evolve, low-income consumer demand could drive companies to increasingly adopt frugal innovation processes (see box).17 Signs of frugal innovation can already be seen in Asia in the production of cars, smartphones, tablets, pharmaceuticals and industrial design,18 as well as in key services such as banking.19 In the smartphone market, while technology leaders, Apple and Samsung, have fought globally over the high-end of the market, new competitors have taken hold of market share in developing Asia. Using frugal methods, China’s Xiaomi has emerged as a dominant smartphone vendor in both India and China20 while India has launched multiple home-grown frugal smartphone vendors of its own. These Indian competitors are making inroads in the low-cost local market, but like Xiaomi, have aspirations for global distribution.21 These companies are seizing market share by concentrating on overlooked consumers22 such as the emerging consumer class, where firms will expect volume to offset razor-thin profit margins.23 The concept of frugal innovation is not entirely new to western business, which has already experimented with many new business models, including hyper-aggressive pricing. For example, leveraging the negligible cost of digital distribution, Google has created an entire ecosystem of free software (so called ‘freemium’ marketing), all of which funnel users to its Internet search tools that derives the majority of its advertising revenue. Amazon, the traditional leader in the global marketplace has operated for 21 years, sacrificing profits for revenue growth. However, new competitors such as China’s Alibaba and its push into western markets24 will put these strategies to the test. If firms (both Asian and western) choose to pursue a frugal development path, this could impact all levels of society as many of the products may be equally appealing to middle class consumers around the world, potentially disrupting many traditional industries and business models.

Figure 1 – Population by wealth category, 2012 and 2030

This figure is entitled “Population by wealth category, 2012 and 2030” and illustrates the global emerging consumer by region. The chart breakdowns the transition between the growth in consumer class and emerging consumers between 2013 and 2030 in the following three regions: Asia (South Asia, Greater China, South East Asia & Oceania); the West (Europe & North America); and the Rest (Latin America, Caribbean, Africa, Middle East & former Soviet Union). In summary, by 2030, Asia will have more consumers than the rest of the world combined.

Frugal innovation

Is a process that “discovers new business models, reconfigures value chains, and redesigns products to serve users who face extreme affordability constraints, in a scalable and sustainable manner. It involves either overcoming or tapping institutional voids and resource constraints to create more inclusive markets”. See video: Rise of the Frugal Economy(link is external) (5:12 mins). India’s Tata Motors makes the Nano car, retailing at about US$ 3,000. The Aakash tablet created for the Indian market currently sells for as low as US$ 55.

Asia’s Emerging Corporations

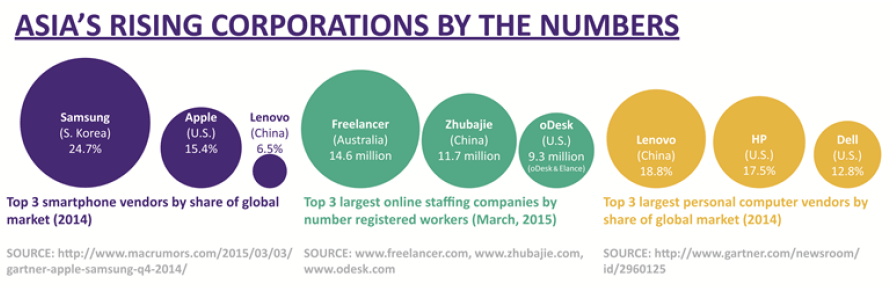

These companies are potentially well-placed to capitalize on the emerging consumer market in Asia, and then use this as a springboard to enter and disrupt higher-priced global markets elsewhere. Contrary to the common perception of Asian corporations as mere followers of innovations developed in Silicon Valley and the West, the business sector of Asia continues to mature, surpassing North America in 2014 as the headquarters of top international corporations,25many of which are emerging as global leaders in innovation (see Figure 2).26 If Asia succeeds in capitalizing on its rising domestic human capital (especially in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) subjects) and in attracting top global talent from research and development(R&D) positions in the West (including the large proportion of Asian graduate students in western universities27 and think tanks), the percentage of Asian-based top global corporations in 2030 may rise significantly. This may create a virtuous circle, driving further investment, trade and market focus in and on Asia.

Figure 2 – Asia’s Rising Corporations by the Numbers

This image illustrates “Asia’s Rising Corporations by the Numbers.”

The emerging digital economy in Asia

Continuing investments and advances in digital infrastructure combined with the unbundling of jobs and the growth of digital services could profoundly reshape the nature of work and commerce. As Internet speeds continue to improve and collaboration technologies mature, inexpensive smartphones, solar chargers and wireless connectivity could afford even the poorest urban and rural Asian citizens an opportunity to participate in the global economy as virtual digital workers, serving customers worldwide.

Leap-frogging Digital Infrastructure

Active state intervention in key Asian countries, such as China and South Korea,28 has led to rapid adoption of more advanced data infrastructure than in many parts of the West that rely exclusively on private providers. Asian nations are leap-frogging existing technologies, building a faster, cheaper digital infrastructure. For example, South Korea’s Internet connections average speeds conservatively measured at 2.5 times faster than those in the Canada for one quarter of the price.29 China has released a plan to spend more than $182 billion on fibre and 4G technologies to boost Internet speeds by the end of 2017.30 Asia’s performance in overall digital preparedness(link is external) has been growing steadily over the past five years while that of most western countries has been stagnant or slipped.31 These growing digital infrastructure investments could position Asia to capitalize on new technologies and dominate key areas of the emerging global economy.

Job Unbundling and Wage Convergence

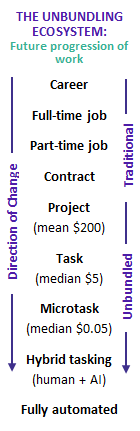

The unbundling of jobs is an ongoing process in which freelancing(link is external) eventually decomposes many jobs to their constituent parts as seen in Figure 3. This allows for more efficient, cost-optimized bidding by workers that is increasingly independent of location. Led by firms such as eLance.com, Freelancer and China’s Zhubajie (at the project level) and by Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (for tasks and micro tasks), Asia holds 5 of the top 10 spots(link is external) 32 for freelancing in a projected $5 billion industry33 in 2015. Nations such as the U.S. are expected to have freelance work represent up to 50% of employment(link is external)34 as early as 2020. Given that much of Asia currently has a significant wage-rate advantage over the West35 and is capitalizing on investments in digital infrastructure, a global move to greater job unbundling could favour Asian workers and trigger an accelerated convergence of global wage-rates.

Figure 3 – The Unbundling Ecosystem

This figure is entitled “The unbundling ecosystem: future progression of work” shows a direction of change from more traditional work to unbundled work. The list moves from traditional to unbundled. Starting from the top and moving downwards we have: career; full-time job, part-time job; contract; project (mean $200); task (median $5); microtask (median $0.05); hybrid tasking (human + AI) and fully automated.

The Rise of Global Digital Services

As industrial processes continue to automate through AI, next-gen robotics,(link is external)36 and the deployment of evolving technologies such as 3D printing(link is external),37 the number of manufacturing jobs in the future is expected to decline significantly both in Asia and in the West(link is external).38 As manufacturing further automates, Asia will likely pursue the development of global digital services as the primary path to raising employment and incomes in Asia.39 Evolving digital tools such as telepresence technologies40 and augmented reality, combined with job unbundling, could greatly assist this transition to a greater provision of digital services via a global virtual workforce.

Ownership unbundling: the collaborative economy and open source

Traditional commerce, where business to business and business-to-consumer interactions dominate, is increasingly being undermined by new business models with radically different pricing schemes. Ownership unbundling reflects two significant forces impacting traditional ownership models — the collaborative (sharing) economy and the open source movement. There are signs that these models are now being adopted in Asian markets and could rapidly grow. Collectively, these new models of interaction allow for much more efficient usage of resources and may significantly undercut existing business models and/or drive down prices. This may have significant consequences for many economic sectors, but provides significant benefits for consumers and may lead to new business opportunities.

Collaborative Economy

The collaborative economy (also called the “sharing economy”41) relies on Internet technologies to connect distributed groups of people, allowing for the better use of goods, skills and other useful services. The collaborative economy depends on people being able to communicate and share information, making it possible to generate trust through meaningful interactions.42 Collaborative economy models have evolved rapidly in the 21st century, facilitated by mobile smart devices and by social media(link is external).43 These new models are now impacting all aspects of the economy, including consumption, production, finance, marketing, and distribution, as seen in Figure 4.44 Examples of the collaborative economy in Asia include the recent US $ 100 million investment in Tujia.com(link is external),45 a Chinese competitor to the accommodation sharing website Airbnb(link is external) and the recent merger(link is external)46 of the top two taxi-hailing services in China in order to counter the arrival of the popular ride-sharing service, Uber(link is external). Revenue from all collaborative business models is expected to have surpassed $15 billion worldwide in 2014, with annual growth exceeding 25%(link is external) 47 and potentially reaching $335 billion by 2025.(link is external)48

Figure 4: Aspects of the Collaborative Economy (text)

Collaborative Consumption

- Zipcar is a car rental company that allows members to share a pool of vehicles.

- Yongche is the mobile platform that connects individual drivers with patrons seeking taxi-services in China, similar to Uber.

- Kijiji is an online platform which facilitates second hand redistribution.

Collaborative Production

- Firefox is an open source web browser developed by a non-profit to promote openness, innovation and participation on the Internet.

- Hackerspaces are community workspaces where people gather to collaborate and share skills, tools and resources. These spaces serve as a launching pad for disruptive new products and startup companies.

Collaborative Learning

- Massive Open Online Courses offer course material forums for students and teachers to interact at a distance. They are considered an affordable alternative to higher eduction.

- Baidu Baike is a free Chinese language Internet collaborative encyclopeida similar to Wikipedia.

Collaborative Finance

- Wujudkan is an Indonesian online crowdfunding platform similar to Kickstarter. These web platforms allow individuals to help fund projects they wish to see realized.

- Lending Club is a marketplace that allows borrowers to connect with individual lenders.

Open Source and Intellectual Property:

Open source represents the free use, modification and sharing of a design or blueprint. The market disruption potential is well established; open source versions of Linux have displaced Microsoft’s proprietary Windows Server product on 67.2% of the world’s web servers49 while Google’s open source Android now runs on 84.4% of smartphones.50 The Asian open source community is currently not large; however major Asian companies such as Huwaei, Baidu and Alibaba51 are investing heavily in open source infrastructures. Further, driven by security concerns, China is planning its own desktop and mobile software to oust imported rivals from Microsoft, Apple and Google.52 In the next 10–15 years, open source will expand into new areas, for instance through the sharing, sale and production of 3D printing templates53 or through synthetic biology, as demonstrated by the International Genetically Engineered Machine(iGEM) competition54 (a worldwide challenge to build simple biological systems). The growth of open source emphasizes that the current western framework for intellectual property (IP) may not be appropriate for Asia as demonstrated by recent pushback from both China(link is external)55 and India(link is external)56 regarding pharmaceuticals, especially if Asian nations pursue frugal business models to meet the demands of an emerging consumer class at prices they can afford. Combined, these forces could serve to disrupt traditional business models, often moving faster than government regulation or taxation policies can react.

Supporting vide

The evolving Sharing Economy in South Korea(link is external) — (1:53 mins)

The potential for social disruption

There are a number of factors that could result in social unrest and catalyze movements for reform as Asia undergoes rapid economic and technological change. Economic growth in the region has been accompanied by rising income inequality, leaving many behind. An estimated one billion people in Asia are still affected by a lack of access to basic social and economic services and employment opportunities, along with poor working conditions.57 The region’s ability to promote equity through public investment, however, will be hindered by a weak tax base and soon the rising costs of addressing aging societies and environmental pressures.58 A concentration of coastal cities with insufficient infrastructure makes Asia among the most vulnerable to climate change disruptions;59 food and water shortages, dislocation, and competition for scarce resources could be sources of future popular discontent and conflict.60 Resource use and degradation of land,61 water62 and air quality,63 a resurfacing of long rooted religious conflicts,64 and recent labour 65 and pro-democracy movements66 are raising issues that could galvanize many Asians in the Internet age. While some Asian countries have a long history of home-grown civil society movements, many Asian governments remain uneasy with social organizing: some countries are only recently increasing their tolerance of such activity (around select issues)67 and many governments continue to suppress political dissent.68 However, as social networks and experience grow, there will likely be more potential for an organized response at the grassroots level on any flashpoint issue. The question is whether such issues will be resolved through dialogue and reform, repression or revolution. With Asia at the centre of both rapid disruption and rising influence, emerging movements there may also articulate alternatives that resonate beyond the local scale, as Maoism and Gandhism have in the past.

An Asian society in transition could alter global norms and values

Asia is in the midst of profound cultural shifts that could impact everything from family relationships to legal and social institutions. As the world further integrates digital technologies, Asia’s growing online presence will make this cultural transformation relevant for all.

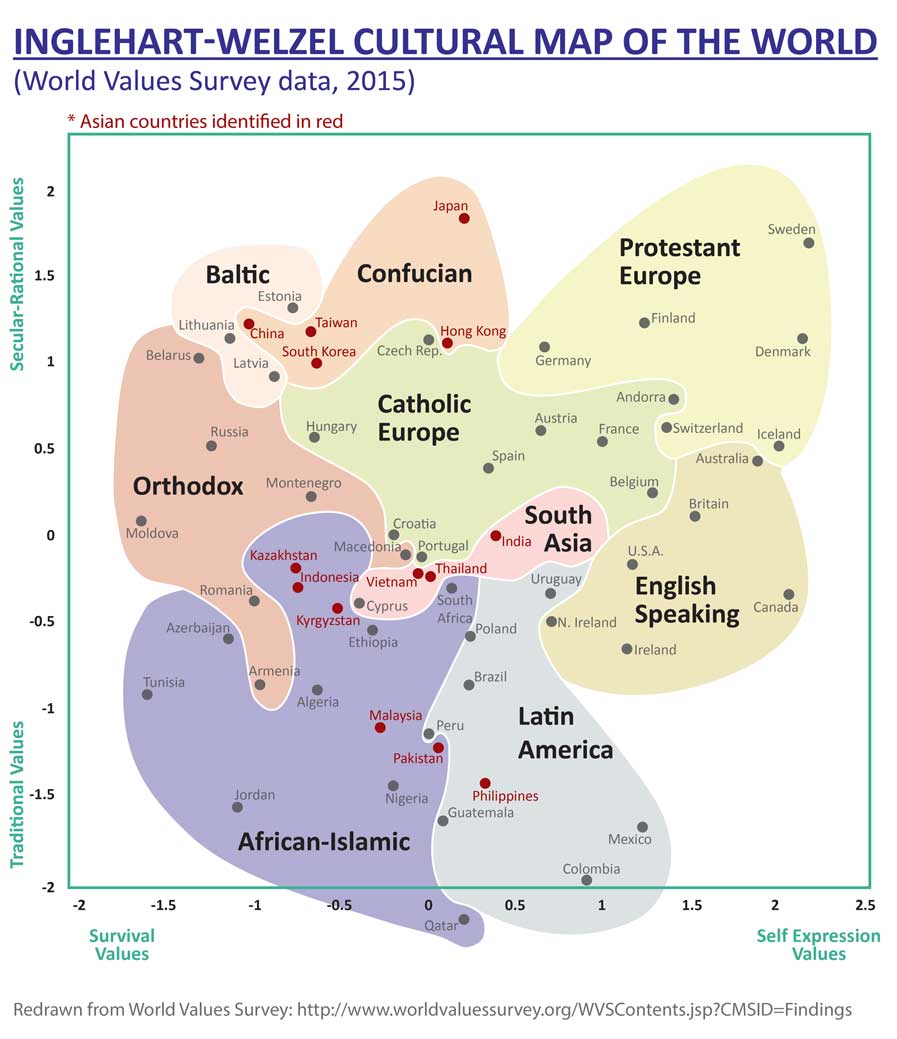

Asia’s Rapidly Changing Norms and Values

The pace of modernization in the world’s fastest growing economic region is creating cultural change, with signs of increased gender equality(link is external),69smaller(link is external) and more diverse families,70 and increased tolerance(link is external) for diversity and nonconformity.71 These changes may be indicative of developing Asia adopting more self-expressionist values (see Figure 5), including a greater interest in individual human rights and a sense of individual agency.72 Such a transition may provoke important debates about the role of government versus family as a source of social support. It may also stir a vibrant civil society and challenge governments to uphold democratic principles. Although this story may, on the surface, seem similar to western historical experience, Asia brings different cultural legacies (collectivist institutions, stronger governments) to a completely different era, with current challenges such as climate change, security and a rapidly changing digital economy. These may require novel responses and lead to ultimate outcomes that are unique and unexpected. For example, the growing participation and influence of Asian nations in international institutions could bring about new definitions of human rights or align global norms and regulations more closely with collectivist values.

Online Asia will be increasingly influential in shaping global norms and culture

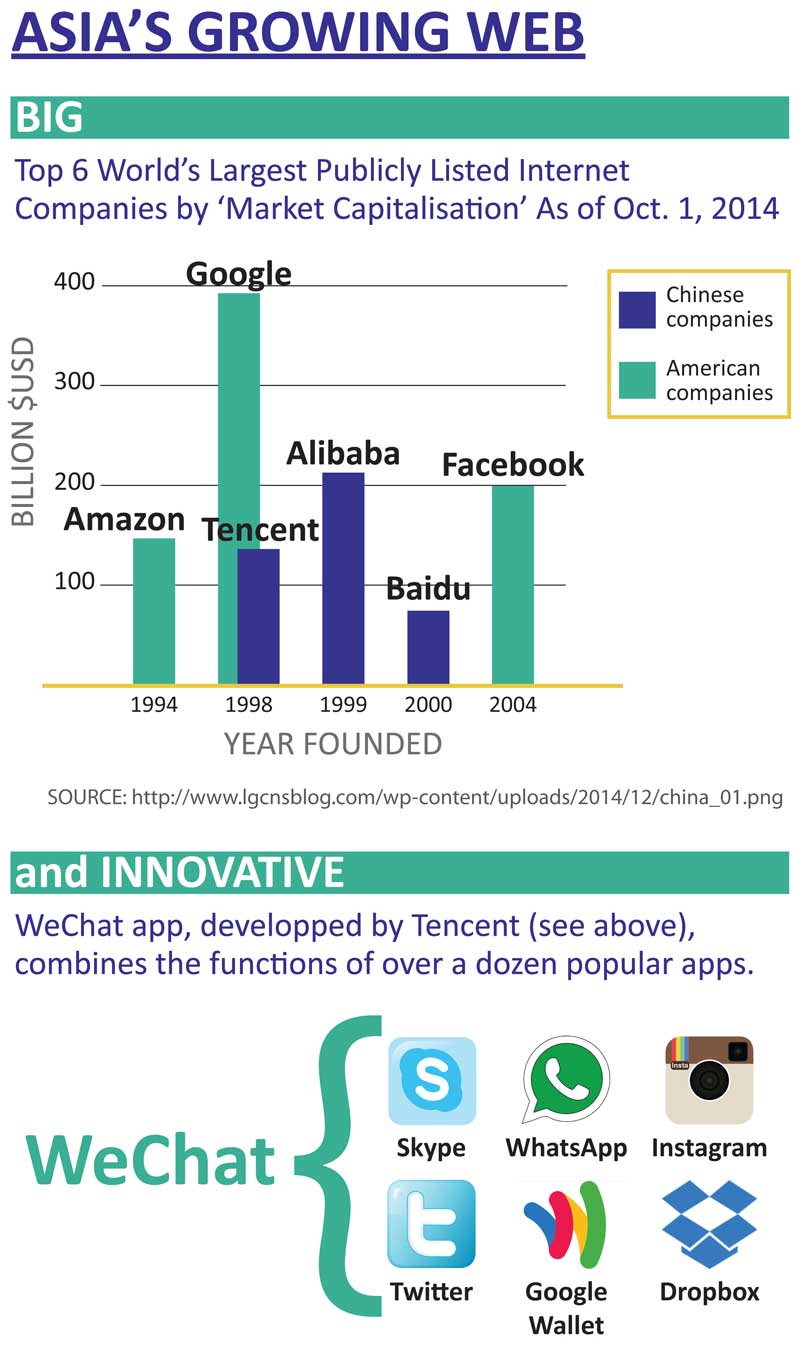

Due to the user-generated nature of Web 2.0 and Asia’s 60% share of the global population, a majority of the content generated online in 2030 will most likely come from Asia. Integrated translation functions will allow this content to be consumed globally — YouTube, Chrome, Skype and WeChat already offer integrated machine translation functions. Asian technology firms are rapidly closing the gap with Silicon Valley (see Figure 6), developing what is arguably the world’s most sophisticated app73 and launching the fastest growing smartphone manufacturer.74The Internet of Things (link is external)75 will allow for the fusion of online and offline dimensions, changing how individuals interact with the world. As Web 3.0(link is external) comes online, there will be a transition to a Knowing Society,76 where real time tracking and live data become central to many aspects of life, positioning an Asian dominated Internet as an integral part of the global creative economy. In summary, a majority of the content, platforms and devices that shape modern digital life could be produced and regulated in Asia, significantly altering the flow of cultural influence.

Figure 5 – Inglehart-Welzel Cultural Map of the World

This diagram is entitled “Inglehart-Welzel Cultural Map of the World.” It uses the World Values Survey data from 2015. The X-axis transitions from Survival Values to Self Expression Values with a scale starting at -2 transitioning to 2.5 at a 0.5 interval. The Y-axis starts with Traditional Values and transitions to Secular-Rational Values with a scale starting at -2 transitioning to 2 at a 0.5 interval.

Figure 6 – Asia’s Growing Web

This diagram is entitled “Asia’s Growing Web.” It is divided in two sections: Big and Innovative. The top section entitled Big includes a bar chart. The bar chart shows the Top 6 world’s largest publicly listed Internet companies by ‘market capitalisation’ as of October 1, 2014. The x-axis is the Year founded and the y-axis is in billions $USD. The first vertical bar is an American company labeled as “Amazon”: founded in 1994 listed at 150 billion $USD. The second vertical bar is an American company labeled as “Google”: founded in 1998 listed at approximately 400 billion $USD. The third vertical bar is a Chinese company labeled as “Tencent”: founded in 1998 listed at approximately at 130 billion $USD. The fourth vertical bar is a Chinese company labeled as “Alibaba”: founded in 1999 listed at approximately 200 billion $USD. The fifth vertical bar is a Chinese company labeled as “Baidu”: founded in 2000 listed at approximately 80 billion $USD. The last vertical bar is the American company labeled as “Facebook”: founded in 2004 listed at 200 billion $USD. The source of this information is HTTP://WWW.LGCNSBLOG.COM/WP-CONTENT/UPLOADS/2014/12/CHINA_01.PNG. The lower box within the diagram is titled “and innovative.” It says “We Chat app, developed by Tencent (see above), combines the functions of over a dozen popular apps.” Below this explanation it has the WeChat icon with parentheses around several other social media platform icons: Skype, Whatsapp, Instagram, Twitter, Google Wallet, and Dropbox.

Asia’s evolving governance models

The Internet is changing citizen-state power dynamics, allowing crowds to hold their governments to account and enabling governments to identify citizen concerns and build legitimacy. Asian examples include the Indian web site ipaidabribe.com(link is external)77 and the Chinese and Korean Human Flesh Search(link is external)78 phenomenon, where crowds recreate event timelines by gathering images online. In response, some governments in Asia79 are developing smart censorship(link is external)80 in order to proactively respond to citizen demands.81 While the Internet is changing citizen-state dynamics across Asia and the globe, its development in single party states is of particular interest. For example, China now employs roughly two million Internet Public Opinion Analysts to monitor social media with the express goal of “stability maintenance(link is external),”82a demonstration of the Communist Party’s increased concern with public approval.83 Crowds are learning to navigate sensitive issues, carefully negotiating progress without a regime change. Some states, previously considered repressive, may gain efficiency and legitimacy, even by-passing the traditional processes of democracy. Digital monitoring and empowered crowds could see authoritarian states evolve into a new model of centralized power: adaptive authoritarianism. In a growing and stable economy, this model could be interpreted as a form of digital direct democracy.

Asia could drive innovation in 21st century social policy

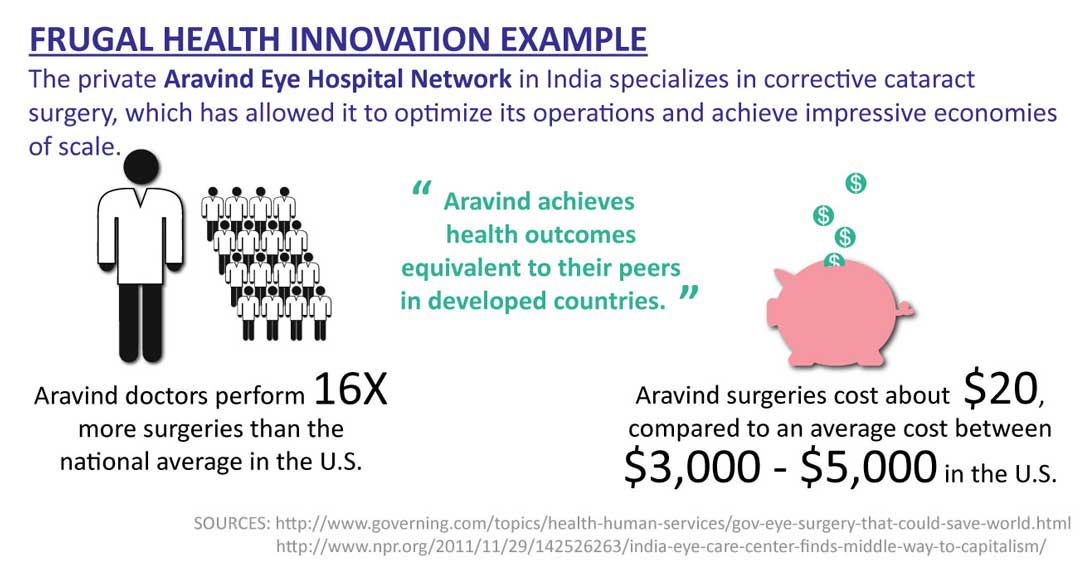

As it navigates a period of rapid change, Asia is developing unique solutions to complex challenges, potentially leapfrogging established models. Across Asia, digital devices(link is external)84 and distribution(link is external)85 are beginning to transform education, and Asia is now the fastest growing market(link is external) for e-learning.86 As Asian governments and businesses continue to promote innovations in e-learning87 to address a large skill gap, they may find ways to provide low-cost, high-caliber education that could evolve into world-leading frugal education models. Rapidly expanding demand for health care in Asia coupled with fewer regulatory constraints on research and development could also make Asia a development ground for new health care tools such as 3D printed body parts(link is external)88 and frugal health care delivery models (see Figure 7).89 As the regional market grows due to a large, aging population, Asia may emerge as a significant exporter of products and services, and a global medical tourism destination.90 In areas where Asia successfully addresses globally relevant challenges — for example, developing efficient and effective forms of a welfare state for the digital era91 — its social policy models could become the ones to emulate.

Figure 7 – Frugal Healty Innovation Example

Examples of Asian innovation in electric mobility

In Japan, Toyota is developing an ultra-compact electric vehicle called “i-ROAD (link is external)”. South Korea has tested an electric bus called “OLEV (link is external)” which can be charged wirelessly on the road while stationary or driving, removing the need to stop at a charging station or building pantograph rail infrastructures. In China, the Kandi EV Car-Share (link is external) program makes electric cars in automated garages available to customers at a rental price of US$ 3.25 per hour, thus removing the high upfront cost barriers associated with ownership.

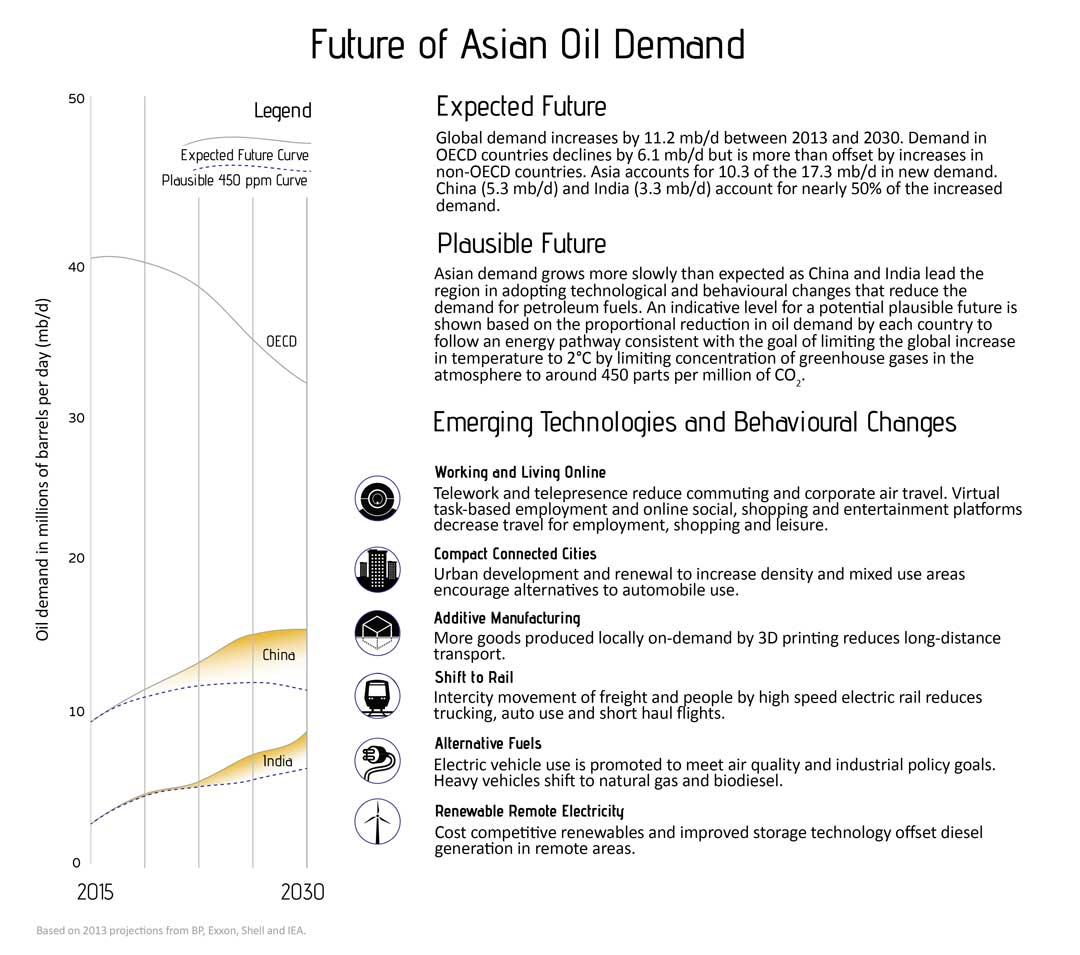

Figure 8 – Future of Asian Oil Demand

This graph is entitled “Future of Asian Oil Demand” and it suggests that Asia’s demands for fossil fuels could peak faster than expected in the next 10-15 years. The left side of the image is line chart with the x-axis representing the year 2015 and 2030 and the y-axis representing oil demand in millions of barrels per day.

The descriptive text running along the right side of the image is positioned under the following three headings: Expected Future; Plausible Future and Emerging Technologies and Behavioural Change.

Expected Future

Global demand increases by 11.2 mb/d between 2013 and 2030. Demand in OECD countries declines by 6.1 mb/d but is more than offset by increases in non-OECD countries. Asia accounts for 10.3 of the 17.3 mb/d in new demand. China (5.3 mb/d) and India (3.3 mb/d) account for nearly 50% of the increased demand.

Plausible Future

Asian demand grows more slowly than expected as China and India lead the region in adopting technological and behavioural changes that reduce the demand for petroleum fuels. An indicative level for a potential plausible future is shown based on the proportional reduction in oil demand by each country to follow an energy pathway consistent with the goal of limiting the global increase in temperature to 2°C by limiting concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to around 450 parts per million of CO2.

Emerging Technologies and Behavioural Changes

Working and Living Online

Telework and telepresence reduce commuting and corporate air travel. Virtual task-based employment and online social, shopping and entertainment platforms decrease travel for employment, shopping and leisure.

Compact Connected Cities

Urban development and renewal to increase density and mixed use areas encourage alternatives to automobile use.

Additive Manufacturing

More goods produced locally on-demand by 3D printing reduces long-distance transport.

Shift to Rail

Intercity movement of freight and people by high speed electric rail reduces trucking, auto use and short haul flights.

Alternative Fuels

Electric vehicle use is promoted to meet air quality and industrial policy goals. Heavy vehicles shift to natural gas and biodiesel.

Renewable Remote Electricity

Cost competitive renewables and improved storage technology offset diesel generation in remote areas.

The structure of energy demand is changing in Asia

Asian demand for oil may peak sooner and decline faster than expected. Asia is shifting from an oil-driven low-cost manufacturing economy to an electricity-driven digital manufacturing and services economy.92 A number of emerging technological and behavioural trends accompanying this structural change could combine to soften Asia’s demand for petroleum-based fuels (see Figure 8). These include increased greater market penetration of electric vehicles(link is external) 93 (see box on next page) and natural gas vehicles(link is external),94 efficiency gains in existing fleets from better logistics, and increased transportation by rail(link is external).95 They also include changes that reduce the need for physical transportation of goods and people, such as additive manufacturing(link is external) (3D printing),96 more virtual work and teleworking enabled by better telepresence technologies(link is external),97 and changes in urban planning that reduce travel distance and increase public transit.98Concerns over energy security,99air pollution(link is external),100 and growing climate change impacts101 may also affect oil demand through policies to reduce imports and use of petroleum-based fuels. Lower Asian oil demand could lead to lower than expected global oil demand. In an attempt to ensure their reserves are fully extracted before oil is replaced as a predominant energy source, low-cost oil producers may keep supply levels high seeking to keep prices low and drive high-cost producers out of the market.

Example

Songdo(link is external) city in South Korea is an example of how the Internet of Things can be implemented throughout an urban centre to realize energy efficiencies.

Asia is shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy

Asia could shift further and faster than expected into a renewable energy based, low carbon economy. Advances in technology coupled with rapid price reductions are making the cost of electricity from renewable sources competitive with fossil fuel generation across most of Asia.102 Through supportive government policies and growing private investment, renewables are being widely deployed in Asia in applications ranging from highly decentralized individual(link is external)103 energy production through to grid-connected mega-projects(link is external).104 International connections of national-level grids and related energy-sharing agreements are increasing renewable energy production on a regional basis by permitting countries connected to “super-grids(link is external)”105 to deploy technologies best matched to their comparative advantages in electricity production from wind, solar, hydro or geothermal energy. Problems related to variable supply from wind and solar are being addressed by advances in storage and distribution management(link is external).106 Electrification of their increasingly digitally-based economies with renewables reduces the need for tradeoffs between increasing energy for economic development and reducing greenhouse gas emissions potentially allowing Asian countries to emerge as leaders in the climate change debate.107 They could increasingly set the international agenda, potentially pushing for ambitious emission reduction targets(link is external)108 and for trade liberalization 109 for renewable energy goods and services as they seek to mitigate their risk from climate change and to capture global market share for low carbon technologies.

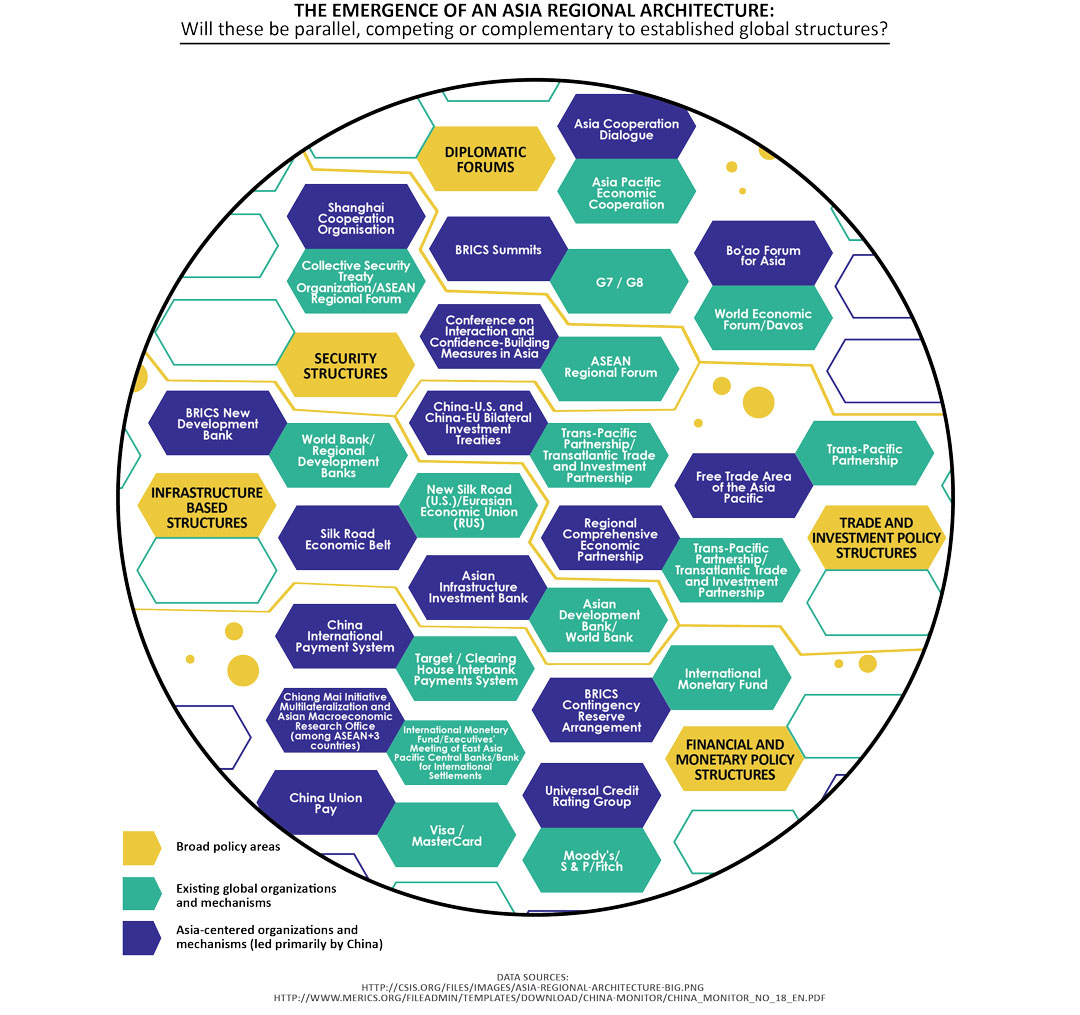

Asia’s institutional architecture could alter international relations

Emerging pan-Asian economic institutions, along with new trade agreements and security arrangements, could disrupt existing international governance structures by providing alternative forums and models to western-dominated institutions, relationships, and norms. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank(link is external) (AIIB), the Silk Road Economic Belt(link is external), and several regional trade proposals, among other initiatives, may create an Asia-Pacific multilateral trade and economic order.110 The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA), and calls for a broader “Asian security concept(link is external)” could likewise provide Asia with a regional security infrastructure offering local solutions to local problems.111 Meeting the region’s demands, Asia’s institutions may displace global institutions from Asia, further insulating Asian countries from the demands placed on them by western-dominated international organizations (see Figure 9). As Asian countries become more assertive in defending regional structures, they may increasingly use Asia’s institutions as political leverage and influence overseas. Eventually, Asia’s institutions could provide a globally competitive and attractive model that gains stature in influencing broader international structures, changing the values, norms, and principles informing the current global order.112

Figure 9 – The emergence of an Asia regional Architecture

This image is entitled “The emergence of an Asia regional Architecture.”

The sources of geopolitical conflict could evolve

Cyber-security and failure to address the problems of fragile states could become new security priorities. A number of factors could trigger traditional geopolitical conflict in Asia: border disputes; xenophobia and nationalism, support to terrorists and fundamentalists, the race for resources; climate change and environmental refugees, and water and food scarcity to name a few. However, two issues will likely demand closer attention. Cyber-security is emerging as a significant and highly disruptive challenge, with cyber threats proliferating “exponentially faster” than the capabilities to respond to them,113 leading to potentially counter-productive reactions such as localized internets.114 The inability to address cyber-terrorism and cyber-crime (link is external)could undermine the emerging digital economy and leave modern societies vulnerable to disruption of critical infrastructure. The other re-emerging security challenge is fragile states. There are more than 50 in the world and six in Asia — most on the border between India and China. Intra-state conflict is an ongoing reality in several Asian fragile states. The potential for one or more of these to collapse and become failed states will likely grow in a period of rapid change. The negative consequences of failed states have been highlighted again by the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Experience in Afghanistan demonstrates the weakness of current international approaches, despite billions of dollars in foreign military intervention and development assistance. There may be increased pressure to rethink how we address failed and fragile states, given the high cost of current approaches — and the even higher costs of failure.

Asia’s digital dark side

Emerging technologies, while providing the engine of Asia’s economic development, could also greatly empower violent individuals, criminal enterprises, and militant groups, in undermining the very foundation upon which Asia’s emerging economy rests. New technology is exposing new vulnerabilities, enabling novel forms of mass disruption and warfare that may be especially attractive to non-state groups.115 Drone technology, cyber currencies, the 3D printing of weaponry, and advancements in robotics and bio-weaponry could further permit individuals and groups to project power across Asia and the world. The rising relative power of Asia’s non-state actors, along with the growing interconnection between ethnicity and politics(link is external), may further erode state power. Loss of territorial control may intensify competition over scarce natural resources and exacerbate food insecurities, leading to further lawlessness, criminality, and piracy.116

Notes

16 Horizons internal calculations based on OECD and World Bank figures. All numbers are in 2014 PPP dollars. Detailed spreadsheet available on request.

Technical note: The economic projections stem from the OECD Prospects to 2060, http://stats.oecd.(link is external)org/economicoutlook/stories/home.xml(link is external) for OECD countries at 2030, with regional regressions based on local income rank and projected growth rates from World Bank data for countries not independently modelled in the OECD Prospects data set. Each country’s population is modelled at 2015 and 2030 using a lognormal income distribution with World Bank household correction, using after-tax and transfer

household Gini coefficients based on the most recent World Bank data available. The numbers of people living in households with after-tax-and-transfer incomes higher than $19500/capita/yr by PPP (the “global consumer class”); and between $9500 and $19500/capita/yr by PPP (the “emerging consumer class”) are tallied and reported on in the infographic and report. These cutoffs correspond closely to the most recent World Bank definitions for a “high income” and “mid-high income” country. The Gini coefficients for inequality are held stationary in time for the default scenario, save for a modest increase through 2030 due to returns increasingly going to a highly-skilled subset of the population, based on Braconier and Ruiz-Valenzuela’s work at the OECD, which was corrected for post-tax-and-transfer in the regions with higher tax and transfer rates.

17 Box on Frugal Innovation

Bhatti, Y. 2011. “What is frugal innovation? Definition.” Frugal-Innovation.com. July 25. http://www.(link is external)frugal-innovation.com/author/yasserbhatti/(link is external)

NESTA video, Rise of the Frugal Economy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NTZem7lCRww(link is external)

Tata Motors: http://www.ibtimes.co.in/tata-nano-twist-active-spied-testing-again-expected-launch-pricefeature-(link is external)details-623077(link is external)

Aakash tablet http://www.akashtablet.com/(link is external)

18 Wikipedia. 2015. “Foldscope.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foldscope(link is external)

19 Bound, K. Thornton, I. 2013. “Our Frugal Future: lessons from India’s innovation Systems.” NESTA. March 16, 2015. http://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/our_frugal_future.pdf(link is external)

20 The Economist. 2015. “The Xiaomi Shock.” http://www.economist.com/news/business/21645217-(link is external)chinas-booming-smartphone-market-has-spawned-genuine-innovator-xiaomi-shock?frsc=dg%7Ca(link is external)

21 The Indian Express. 2014. “Xiaomi now third largest smartphone maker, Indian companies more dominant at home: Canalys.” http://indianexpress.com/article/technology/mobile-tabs/(link is external)

xiaomi-now-no-3-globally-indian-companies-becoming-more-dominant-at-home-canalys/(link is external)

22 Fannin, Rebecca. 2013. “Frugal Innovation Evolves in the the Next Phase of China’s Rise as Tech Economy.” Forbes. November 19. http://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccafannin/2013/11/19/(link is external)frugal-innovation-evolves-in-the-next-phase-of-chinas-rise-as-tech-economy/(link is external)

23 Yarrow, J. 2015. “Apple is taking 93% of the profits in the smartphone insustray now.” Business Insider. March 13, 2015. http://uk.businessinsider.com/(link is external)apple-is-taking-93-of-the-profits-in-the-smartphone-industry-now-2015-2(link is external)

24 Chan, E. Carsten, P. Ruwitch, J. 2015. “Alibaba in major initiative to court China consumer for U.S. retailers.” Reuters. March 16, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/16/(link is external)us-alibaba-group-usa-china-insight-idUSKBN0KP0F620150116(link is external)

25 Bainsbridge, Andrew. 2015. “Waiting in the Wings- Asia’s next Tata and Alibaba.” Standard Chartered – Beyond Borders. January 21. https://www.sc.com/BeyondBorders/waiting-wings-asias-next-tata-alibaba/(link is external)

26 Pilling, D. 2015. “Corporate China not yet ready to rule the world.” Financial Times. February 4. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/6a89acf6-ac58-11e4-9d32-00144feab7de.html#axzz3RSaYfuUw.(link is external)

27 Kono, Y. 2014. “Inernational Student Mobility Trends 2014: The upward momentum of STEM fields.” World Education News and Review. March 5, 2015. http://wenr.wes.org/2014/03/international-student-mobility-trends-2014-the-upward-momentum-of-stem-fields/(link is external)

28 Neal, Meghan. 2014. “South Korea’s Internet Is About to Be 50 Times Faster Than Yours.” Motherboard Vice. January 22. http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/south-koreas-internet-is-about-to-be-50-times-faster-than-yours.(link is external)

29 OECD. “OECD Broadband Portal.” Feburary 19. http://www.oecd.org/internet/broadband/(link is external)oecdbroadbandportal.htm(link is external)

30 Carsten, Paul. 2015. “China will spend $182 billion to boost Internet speed by the end of 2017.” Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/05/20/us-china-internet-idUSKBN0O50JH20150520(link is external)

31 “Digital Revolution Index.” MasterCard Insights. http://insights.mastercard.com/digitalevolution/(link is external)

32 Elance. 2013. “Global Online Employment Report.” https://www.elance.com/q/node/1578?mpid=cj_10777892_4003003(link is external)

33 Magdirila, Phoebe. 2013. “Elance records 90% more jobs for Philippine freelancers this year.” Tech in Asia. August 23. https://www.techinasia.com/elance-jobs-philippine-freelancers-trust-global-businesses/(link is external)

34 Forbes. 2013. “How An Exploding Freelance Economy Will Drive Change In 2014.” November 25. http://www.forbes.com/sites/groupthink/2013/11/25/how-an-exploding-freelance-economy-will-drive-change-in-2014/(link is external)

35 Wikipedia. 2015. “List of countries by average wage.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_average_wage(link is external)

36 Reuters. 2015. “Robot replacements for Foxconn’s workers.” January 28. http://www.reuters.com/video/2015/01/28/robot-replacements-for-foxconns-workers?videoId=363019897(link is external)

37 Mearian, Lucas. 2014. “HP’s move into 3D printing will radically change manufacturing.” Computer World. October 31. http://www.computerworld.com/article/2841414/hps-move-into-3d-printing-willradically-(link is external)change-manufacturing.html(link is external)

Millward, Steven. 2015. “China just 3D-printed an entire mansion. Here’s what it looks like.” Tech in Asia. January 19. https://www.techinasia.com/china-3d-printed-mansion-and-tower-block/(link is external)

38 Thompson, Derek. 2014. “Here are the 47% of Jobs at high risk of being destroyed by robots.” Business Insider. January 24. http://www.businessinsider.com/robots-overtaking-american-jobs-2014-1(link is external)

39 Donghyun, Park, and Shin Kwanho. 2012. “The Service Sector in Asia: Is It an Engine of Growth.” Asian Development Bank. December. http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2013/10825.pdf(link is external)

40 Olson, Parmy. 2013. “Rise of the Telepresence Robots.” Forbes. June 27. http://www.forbes.com/sites/(link is external)parmyolson/2013/06/27/rise-of-the-telepresence-robots/(link is external)

41 Owyang, J. 2014.”Collaborative Economy Honeycomb.” Crowd Companies. December 14. http://crowdcompanies.com/blog/collaborative-economy-honeycomb-2-watch-it-grow/(link is external)

42 Stokes, Kathleen, Emma Clarence, Lauren Anderson, and April Rinne. 2014. “Making Sense of the UK Collaborative Economy.” Nesta. September. http://www.nesta.org.uk/sites/default/files/(link is external)

making_sense_of_the_uk_collaborative_economy_summary_fv.pdf(link is external)

43 Holmes, Ryan. 2014. “Travel Buddies and Toilets: How Social Media Jumpstarted the Share-everything Economy.” Hootsuite. http://blog.hootsuite.com/how-social-media-jumpstarted-the-sharing-economy/44(link is external)

44 References for each section of diagram as follows:

Collaborative consumption

Zipcar: http://www.zipcar.ca/(link is external)

Yongche: http://www.yongche.com/(link is external)

Kijiji: http://kijijiblog.ca/about-us/(link is external)

Collaborative production

Firefox: https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/(link is external)

Hackerspaces: http://www.hackerspaces.org/(link is external)

Collaborative learning

Massive Open Online Courses: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massive_open_online_course(link is external)

Baidu Baike: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baidu_Baike(link is external)

Collaborative finance

Wujudkan: https://wujudkan.com/(link is external)

Lending Club: https://www.lendingclub.com/(link is external)

45 Cheung, Sonja. 2014. “China’s anser to Airbnb, Tujia.com raises $100M.” WSJ. June 18. http://blogs.wsj.(link is external)com/venturecapital/2014/06/18/chinas-answer-to-airbnb-tujia-com-raises-100m/(link is external)

46 Westlake, Adam. 2015. “Uber faces increased competition in China as top 2 rivals merge.” Slash Gear. February 15. http://www.slashgear.com/uber-faces-increased-competition-in-china-as-top-2-rivals-merge-15369166/(link is external)

47 Geron, Tomio. 2013. “Airbnb and The Unstoppable Rise Of The Share Economy.” Forbes. January 23. http://www.forbes.com/sites/tomiogeron/2013/01/23/airbnb-and-the-unstoppable-rise-of-the-share-economy/(link is external)

48 PWC. 2014. “Five key sharing conomy sectors could generate £9 of UK revenue by 2025.” August 15. http://pwc.blogs.com/press_room/2014/08/five-key-sharing-economy-sectors-could-generate-9-billionof-(link is external)

uk-revenues-by-2025.html(link is external)

49 W3 Techs. 2015. “Usage of operating systems for websites.” March 18. http://w3techs.com/(link is external)technologies/overview/operating_system/all.(link is external)

50 IDC. 2015. “Smartphone OS Market Share, Q3 2014.” http://www.idc.com/prodserv/smartphone-osmarket-(link is external)share.jsp.(link is external)

51 Say, M. 2014. “China will change the way all software is bought and sold.” ReadWrite. March 13, 2015. http://readwrite.com/2014/08/11/china-opensource-software-ip-programmers-united-states(link is external)

52 Gibbs, S. 2014. “China wants to repalce Microsoft, Apple and Android softwaer by October.” Business Insider. March 13, 2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/china-wants-to-replace-microsoft-apple-and-android-software-by-october-2014-8(link is external)

53 Shapeways. 2015. “Shapeways: About us.” http://www.shapeways.com/about?li=footer(link is external)

54 iGEM. 2015. “IGEM/Learn about: What is the iGEM competition.” http://igem.org/wiki/index.php title=IGEM/Learn_About(link is external)

55 Sen, Amiti. 2012. “India, Brazil & China defend generic drugs at WTO.” India Times. June 25. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2012-06-25/news/32409062_1_counterfeit-medicines-fake-drugs-generic-drugs(link is external)

56 Kilday, Lisa. 2013. “Global IP Reaction to India’s Rejection of the Novartis Drug Patent.” IPWatchdog. May 28. http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2013/05/28/global-ip-reaction-to-indias-rejection-of-the-novartis-drug-patent/id=40778/(link is external)

57 International Labour Organization. Local development for decent work. http://www.ilo.org/asia/(link is external)decentwork/adwd/WCMS_098229/lang–en/index.htm(link is external)

58 During the 2000s, the ratio of tax revenue to GDP averaged 18.8% in developing Asia, compared to the global average of 28.6%. http://www.adb.org/news/developing-asia-should-use-public-spending-narrow-inequality(link is external)

59 ZDNet. 2012. “Asian cities at highest risk to climate change, study says.” November 12, 2012. http://www.zdnet.com/article/asian-cities-at-highest-risk-to-climate-change-study-says/(link is external)

60 McKie, R. 2014. “Global warming to hit Asia hardes, warns new report on climate change.” The Guardian. March 22, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/22/global-warming-hit-asia-hardest(link is external)

61 Khor, Martin. Global Policy Forum. “Land Degradation Causes $10 Billion Loss to South Asia Annually. https://www.globalpolicy.org/global-taxes/49705-land-degradation-causes-10-billion-loss-to-southasia-(link is external)

annually-.html(link is external)

62 U.S. Geological Survey. 2014. Pollutants Pose Threat to Mekong River Residents. February 27, 2014. http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=3813&from=rss#.VVN5rflVhBc(link is external)

63 Global Times. 2014. “Smog pushes emigration.” February 27, 2014. http://www.globaltimes.cn/(link is external)content/845032.shtml(link is external)

64 Croissant, A and Trinn, C. 2009. “Culture, Identity and Conflict in Asia and South-east Asia.” January 2009. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/md/politik/personal/croissant/forschung/croissant_trinn_2009_asien.pdf(link is external)

The Economist. 2014. “The plural society and its enemies.” August 2, 2014. http://www.economist.com/(link is external)news/asia/21610285-our-departing-south-east-asia-correspondent-explains-how-plural-societyremains-(link is external)key(link is external)

The Economist. 2013. “Fears of a new religious strife.” July 25, 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/(link is external)asia/21582321-fuelled-dangerous-brew-faith-ethnicity-and-politics-tit-tat-conflict-escalating(link is external)

65 The Wall Street Journal. 2014. “Crackdown Upends Cambodia Labor Movement’s Show of Strength.” January 13, 2014. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303754404579312142849073778(link is external)

Radio Free Asia. Burmese, Cambodians Mark International Workers’ Day with Wage Protests. May 1, 2015. http://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/workers-05012015190714.html(link is external)

Quartz. China’s “factory girls” have grown up – and are going on strike. March 10, 2015. http://qz.com/351393/chinas-factory-girls-have-grown-up-and-are-going-on-strike/(link is external)

66 NewStatesman. Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement is a challenge to all of Asia’s autocrats. October 2, 2014 http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/10/hong-kongs-pro-democracy-movement-challenge-all-asias-autocrats(link is external)

Palatino, Mong. 2014. “Coup Revives Thailand’s Democracy Movement.” The Diplomat. May 27, 2014. http://thediplomat.com/2014/05/coup-revives-thailands-democracy-movement/(link is external)

67 The Asia Foundation. 2012. “Civil Society in Vietnam: A Comparative Study of Civil Society Organizations in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City”. October 2012. https://asiafoundation.org/resources/pdfs/(link is external)

CivilSocietyReportFINALweb.pdf(link is external) (Vietnam)

Gao, Ruge. 2013. “Rise of Environmental NGOs in China: Official Ambivalence and Contested Messages.” The Journal of Political Risk, Vol. 1, No. 8, December 2013. http://www.jpolrisk.com/rise-of-environmental-ngos-in-china-official-ambivalence-and-contested-messages/(link is external)

Asian Development Bank. “Civil Society Briefs: Lao People’s Democratic Republic.” http://www.adb.org/(link is external)sites/default/files/publication/28968/csb-lao.pdf(link is external)

68 BBC News. Vietnam internet restrictions come into effect. September 1, 2013. http://www.bbc.com/(link is external)news/world-asia-23920541(link is external)

ChinaFile. Are Ethinic Tensions on the Rise in China? February 13, 2014. http://www.chinafile.com/(link is external)conversation/are-ethnic-tensions-rise-china(link is external)

The Globe and Mail. “In remote Xinjiang province, Uighurs are under siege.” August 15, 2014. http://www.(link is external)theglobeandmail.com/news/world/inside-chinas-war-on-terror/article20074722/(link is external)

DW. Persecution hinders human rights activities in Bangladesh. July 1, 2014. http://www.dw.de/(link is external)persecution-hinders-human-rights-activities-in-bangladesh/a-17749851(link is external)

Human Rights Watch. Laos remains silent on civil society leader missing for two years. January 9, 2015. http://www.hrw.org/news/2015/01/08/laos-remains-silent-civil-society-leader-missing-two-years(link is external)

Aljazeera. “Pakistan passes tough anti-terrorism law. July 4, 2014.” http://www.aljazeera.com/news/(link is external)asia/2014/07/pakistan-passes-tough-anti-terrorism-law-20147214141127451.html(link is external)

69 SciDevNet. 2014. “More Asian women find success in science.” October 4. http://www.scidev.net/asiapacific/(link is external)gender/feature/more-asian-women-find-success-in-science.html(link is external)

70 Kotkin, Joel. 2012. “Decline of the Asian Family: Drop in Marriages, Births, Threatens Economic Ascendancy.” Forbes. October 23. http://www.forbes.com/sites/joelkotkin/2012/10/23/(link is external)

the-decline-of-the-asian-family-drop-in-marriages-births-threaten-economic-ascendancy/(link is external)

71 Kwaak, Jeyup S. 2013. “Poll Shows Koreans Warming to Homosexuality.” The Wall Street Journal. June 12. http://blogs.wsj.com/korearealtime/2013/06/12/poll-shows-koreans-warming-to-homosexuality/(link is external)

72 World Values Survey. Findings and Insights. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.(link is external)jsp?CMSID=Findings(link is external)

73 Horwitz, J. 2014. “5 ways China’s WeChat is more innovative than you think.” Tech in Asia. February 7. https://www.techinasia.com/5-ways-wechat-is-innovative/(link is external)

74 O’Brien, Chris. 2015. “Samsung who? New phablets mean it’s Xiaomi vs Apple in battle for mobile’s future.” VentureBeat News. January 15. http://venturebeat.com/2015/01/15/(link is external)samsung-who-new-phablets-mean-its-xiaomi-vs-apple-in-battle-for-mobiles-future/(link is external)

75 Cisco. 2015. “Internet of Everything: IoE.” http://www.cisco.com/web/about/ac79/innov/IoE.html(link is external)

76 European Internet Foundation. 2014. “The Digital World in 2030.” https://www.eifonline.org/(link is external)digitalworld2030.html(link is external)

77 Goyal, Malini. 2012. “Ipaidabribe.com: A website that encourages Indians to share their bribe giving experiences.” The Economic Times. December 2. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.(link is external)com/2012-12-02/news/35530547_1_ipaidabribe-com-financially-responsible-corporate-conduct-bribery(link is external)

78 Levine, Jessica. 2012. “What a “Human Flesh Search” Is, And How It’s Changing China.” Tea Leaf Nation. October 4. http://www.tealeafnation.com/2012/10/(link is external)what-a-human-flesh-search-is-and-how-its-changing-china/(link is external)

79 The Economist. 2013. “China’s Internet: A giant cage.” April 4. http://www.economist.com/news/(link is external)special-report/21574628-internet-was-expected-help-democratise-china-instead-it-has-enabled(link is external)

80 Reynolds, Emma. 2014. “China’s internet censorship machine has become even more advanced to cope with social media.”news.com.au. September 12. http://www.news.com.au/technology/online/(link is external)chinas-internet-censorship-machine-has-become-even-more-advanced-to-cope-with-social-media/(link is external)story-fn5j66db-1227056004179(link is external)

81 “China Media Bulletin: Issue No. 91: Party officials mine online chatter as WeChat challenges Weibo dominance.” The Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/article/china-media-bulletin-issue-no-91#9(link is external)

82 Fong, Michelle. 2014. “China Monitors the Internet and the Public Pays the Bill.” Global Voices Advocacy. July 29. http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/2014/07/29/china-monitors-the-internet-and-the-public-pays-the-bill/(link is external)

83 Watt, Louise. 2015. “China courts public with a ‘sensitive’ approach to waste.” Japan Times. January 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/01/27/asia-pacific/politics-diplomacy-asia-pacific/chinacourts-(link is external)

public-sensitive-approach-waste/#.VONGxfnF_g0(link is external)

84 Adkins, Sam. 2012. “The Asia Market for Self-paced eLearning Products and Services: 2011-1616 Forecast and Analysis.” Ambient Insight. October. http://www.ambientinsight.com/Resources/Documents/AmbientInsight-2011-2016-Asia-SelfPaced-eLearning-Market-Abstract.pdf(link is external)

85 The Open University of China. 2014. “Courses Go Online on the World’s First Chinese MOOC Platform.” http://en.ouchn.edu.cn/index.php/news-109/academic-news/1058-courses-go-online-on-the-worlds-first-chinese-mooc-platform(link is external)

86 Docebo. 2014. “E-Learning Market Trends & Forecast 2014-2016 Report.” March. https://www.docebo.(link is external)com/landing/contactform/elearning-market-trends-and-forecast-2014-2016-docebo-report.pdf(link is external)

87 Gratton, Lynda. 2011. “The Skill Gap: Asian Style.” Forbes. October 14. http://www.forbes.com/sites/(link is external)lyndagratton/2011/10/14/the-skill-gap-asian-style/(link is external)

88 Russon, Mary-Ann. 2014. “Chinese Doctors Use 3D-Printing in Pioneering Surgery to Replace Half of Man’s Skull.” International Business Times. August 29. http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/(link is external)chinese-doctors-use-3d-printing-pioneering-surgery-replace-half-mans-skull-1463148(link is external)

89 Scott, Dylan. 2013. “The $20 Eye Surgery That Could Save the World.” Governing the States and Localities. February. http://www.governing.com/topics/health-human-services/gov-eye-surgery-thatcould-(link is external)save-world.html(link is external)

90 The Economist: Intelligence Unit. “A regional medical-tourism hub.” http://www.eiu.com/industry/(link is external)article/642338448/a-regional-medical-tourism-hub/2014-10-01(link is external)

91 The Economist. “Asian Welfare states: new cradles to graves.” http://www.economist.com/(link is external)node/21562210(link is external)

92 McKinsey & Company. 2014. “China’s digital transformation.” July. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/(link is external)high_tech_telecoms_internet/chinas_digital_transformation(link is external)

ExxonMobil. 2015. The Outlook for Energy: A View to 2040. ExxonMobil: Texas, United States. p.34. http://(link is external)

cdn.exxonmobil.com/~/media/Reports/Outlook%20For%20Energy/2015/2015-Outlook-for-Energy_printresolution.pdf(link is external)

McKinsey & Company. 2013. “What’s next for China?” January. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/(link is external)asia-pacific/whats_next_for_china(link is external)

McKinsey & Company. 2013. “China’s e-tail revolution.” March. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/(link is external)asia-pacific/china_e-tailing(link is external)

Springfield, Cary. 2015. “Indian economy growth sectors and significant opportunities.” International Banker. http://internationalbanker.com/finance/indian-economy-growth-sectors-significant-opportunities/(link is external)

Bhargava, Yuthika. 2015. “India has second fastest growing services sector.” The Hindu. February 23. http://www.thehindu.com/business/budget/india-has-second-fastest-growing-services-sector/(link is external)article6193500.ece#comments(link is external)

93 ABB. 2014. “China rolls out the world’s largest electric car charging network.” February 12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UkYHxiSrsHY(link is external)

94 Ro, Sam. 2013. “Chart: The Global Rise of The Natural Gas Vehicles.” Business Insider. June 10. http://www.businessinsider.com/global-natural-gas-vehicle-growth-2013-6(link is external) Government of India. 2012. National Electric Mobility Mission Plan 2020. August. http://dhi.nic.in/NEMMP2020.pdf(link is external)

Peixe, Joao. 2012. “China Targets 5 Million Electric Vehicles by 2020.” Oilprice.com. July 17.

The China Post. 2014. “Korea aims for 200,000 electric cars by 2020.” December. http://www.chinapost.(link is external)com.tw/asia/korea/2014/12/22/424581/Korea-aims.htm(link is external)

Kandi. 2015. “Kandi Technologies Announces the Expansion of Micro Public EV Sharing Program to Nine

Chinese Cities with 14,398 pure EVs Delivered as of the end of 2014.” January, 7: “As of the end of 2014,

there have been a total of 9,852 Kandi Brand electric vehicles (“EVs”) delivered to Hangzhou, 686 EVs to

Shanghai, 1,020 EVs to Chengdu, 340 EVs to Nanjing, 700 EVs to Guangzhou, 612 EVs to Wuhan, 388 EVs

to Changsha, 500 EVs to Changzhou, and 300 EVs to Rugao.” http://en.kandivehicle.com/NewsDetail.(link is external)aspx?newsid=189(link is external)

Navigant Research. 2012. “Electric Scooters in Asia Pacific Will Increase Nearly Tenfold from 2012 to 2018.” October 4. http://www.navigantresearch.com/newsroom/electric-scooters-in-asia-pacific-will-increase-nearly-tenfold-from-2012-to-2018.(link is external)

95 Guilin China International Travel Service. “Important Hihg-Speed Rail Lines in China.” China Highlights. http://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/transportation/china-high-speed-rail.htm(link is external)

Binglin, Chen. 2015. “Wireless rail in on track as China seeks to develop world-first power system.”

South China Morning Post. February 15. http://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/technology/article/1713454/(link is external)

wireless-rail-track-china-seeks-develop-world-first-power(link is external).

BBC. 2014. China: High Speed Rail Network to Be Doubled. January 13. https://www.youtube.com/(link is external)

watch?v=_j2yT5SIaDQ(link is external)

96 Licata, John. 2013. “How 3D printing could revolutionise the solar energy industry.”

The Guardian. February 22. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/blog/2013/(link is external)

feb/22/3d-printing-solar-energy-industry(link is external)

Deloitte University Press. 2014. “Additive manufacturing: A 3D opportunity.” April 8. http://dupress.com/(link is external)

articles/additive-manufacturing-3d-opportunity-video/(link is external)

Fingas, Jon. 2014. “3D-printed wind turbine puts 300W of power in your backpack.” Engadget. August 17.

http://www.engadget.com/2014/08/17/airenergy-3d-wind-turbine/(link is external)

Gebler, M. et al. 2014. “A global sustainability perspective on 3D printing technologies.” Energy

Policy. ScienceDirct. November. p. 158-167 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/(link is external)

S0301421514004868(link is external)

Kreiger, Megan et al. 2013. “Environmental Life Cycle Analysis of Distributed Three-Dimensional Printing

and Conventional Manufacturing of Polymer Products.” ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 1 (12): 151.

http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/sc400093k(link is external)

Christian, Matthew DeVuono, and Joshua M. Pearce. 2013. “Distributed recycling of waste polymer into

RepRap feedstock.” Rapid Prototyping Journal. Volume 19 Issue: 2, 118. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/(link is external)

action/doSearch?ContribStored=Baechler%2C+C(link is external)

97 Hill, David. 2012. “U.S. Being Left in The Dust Of The Global Telecommuting Revolution.” SingularityHub.

Feb 21. http://singularityhub.com/2012/02/21/u-s-being-left-in-the-dust-of-the-globaltelecommuting-(link is external)

revolution/(link is external)

Hickey, Karen. 2013. “What the world thinks of telecommuting.” Infographic. June 12. http://www.ipass.(link is external)

com/blog/what-the-world-thinks-of-telecommuting-infographic/(link is external)

Verdantix. 2010. Carbon Disclosure Project Study 2010: The Telepresence Revolution. https://www.(link is external)

cdproject.net/CDPResults/Telepresence-Revolution-2010.pdf(link is external)

Double Robotic, Double + Portalarium. October 11, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/(link is external)

watch?v=1sICyevgBXw(link is external)

Cisco. 2014. Cisco Telepresence Vision Future Technology. November 15. https://www.youtube.com/(link is external)

watch?v=-yvLSCGwHw0(link is external)

98 Siemens. 2014. The Mobility Opportunity. http://www.siemens.com/press/pool/de/feature/2014/(link is external)

infrastructure-cities/2014-06-mobility-opportunity/Study-mobility-opportunity-preview.pdf(link is external)

The Wall Street Journal. 2015. “China Amps Up an Old Dream of Green Belts.” January 8. http://blogs.wsj.(link is external)

com/chinarealtime/2015/01/08/china-amps-up-an-old-dream-of-green-belts/(link is external)

99 Asian Development Bank. 2013. “Energy Access and Energy Security in Asia and the Pacific.” December.

http://www.adb.org/publications/energy-access-and-energy-security-asia-and-pacific(link is external)

Sankar, T.L. et al. Regional Energy Security for South Asia: Regional Report. Energy for South Asia.

http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADS866.pdf(link is external)

100 Asian Development Bank. 2012. Key Indicator for Asia and the Pacific: Highlights. p.3. http://www.adb.(link is external)

org/publications/key-indicators-asia-and-pacific-2012(link is external)

Qiu, Jane. 2012. “Megacities pose serious health challenge.” Nature. October 12. http://www.nature.com/news/megacities-pose-serious-health-challenge-1.11495(link is external)

Le Monde. 2014. Chine: Comprendre l’ampleur de la pollution en trois minutes. le 13 février.

http://www.lemonde.fr/planete/video/2014/02/13/chine-comprendre-l-ampleur-de-la-pollution-en-troisminutes_(link is external)

4366169_3244.html(link is external)

EuroNews. 2013. Toxic Smog Chokes India Capital. February 1. https://www.youtube.com/(link is external)

watch?v=6_HXEHf6IPg(link is external)

101 IPCC. 2014. “Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability.” Chapter 24. http://www.(link is external)

ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/index_fr.shtml(link is external)

Foreign Policy. 2014. “Why South Asia Is So Vulnerable to Climate Change.” April 22. http://foreignpolicy.(link is external)

com/2014/04/22/why-south-asia-is-so-vulnerable-to-climate-change/(link is external)

102 International Renewable Energy Agency. 2015. Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2014. January.

Figure 2.1, p. 27. http://www.irena.org/DocumentDownloads/Publications/IRENA_RE_Power_(link is external)

Costs_2014_report.pdf(link is external)

Parkinson, Giles. 2015. “Solar Costs Will Fall Another 40% in 2 Years.” Renew Economy. January 20.

http://reneweconomy.com.au/2015/why-solar-costs-will-fall-another-40-in-just-two-years-21235(link is external)

Deutsche Bank. 2015. “Deutsche Bank’s 2015 solar outlook: accelerating investment and cost

competitiveness.” January 13. https://www.db.com/cr/en/concrete-deutsche-banks-2015-solaroutlook.(link is external)

htm(link is external): “Unsubsidized rooftop solar electricity costs anywhere between $0.13 and $0.23/kWh

today, well below retail price of electricity in many markets globally. The economics of solar have

improved significantly due to the reduction in solar panel costs, financing costs and balance of system

costs. We expect solar system costs to decrease 5-15% annually over the next 3+ years which could result

in grid parity within ~50% of the target markets. If global electricity prices were to increase at 3% per

year and cost reduction occurred at 5-15% CAGR, solar would achieve grid parity in an additional ~30% of

target markets globally. We believe the cumulative incremental total available market for solar is currently

around ~140GW/year and could potentially increase to ~260GW/year over the next 5 years as solar

achieves grid parity in more markets globally and electric capacity needs increase.”

103 World Bank. 2013. Women Empowered by Solar Energy in Bangladesh. August 6. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6K7q7l_BAAk(link is external)

104 Mathews, John A. and Hao Tan. 2014. “Economics: Manufacture renewables to build energy security.”

September 10. Nature. Volume 513, Issue 7617.

International Energy Agency. 2014. “World Energy Outlook 2014.” November 12. p. 240.

Larson, Christina. 2014. “China’s Coal Demand May Peak Before 2020.” Bloomberg Business. December.

The Energy Collective. 2015. “China’s Coal Consumption Fell in 2014.” January. http://theenergycollective.(link is external)

com/lauri-myllyvirta/2187741/it-s-official-china-s-coal-consumption-fell-2014(link is external)

GeoBeats News. 2013. World’s Largest Solar Power Plant to Be Built in India. September 26. https://www.(link is external)

youtube.com/watch?v=PLf6aVxUMYI(link is external)

WildFilmsIndia. 2014. Massive solar installation at Thailand’s Sunny Bangchak PV power plant. June 24.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRUgIzndkMw(link is external)

105 South Asia made a regional super electricity grid a reality in November 2014 with the signature of

the SAARC Framework Agreement for Energy Cooperation (Electricity), “realizing the common benefits

of cross-border electricity exchanges and trade among the SAARC Member States leading to optimal

utilization of regional electricity generating resources, enhanced grid security, and electricity trade arising

from diversity in peak demand and seasonal variations.”

South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. 2014. “SAARC Framework for Energy Cooperation

(Electricity).” November 27. http://www.saarc-sec.org/userfiles/SAARC-FRAMEWORK-AGREEMENT-FORENERGY-(link is external)

COOPERATION-ELECTRICITY.pdf(link is external)

Breyer et al. 2014. North-East Asian Super Grid: Renewable Energy Mix and Economics. 6th World

Conference of Photovoltaic Energy Conversion.

Song, Jinsoo. 2014. “Super Grid in North-East Asia Through Renewable Energy.” Techmonitor. http://www.(link is external)

techmonitor.net/tm/images/2/2d/14jan_mar_sf3.pdf(link is external)

KEPCO. 2013. “Energy Co-operation through Establishing North-East Asia Supergrid.”

The Daily Bangladesh. 2014. “Handshake, signatures salvage Saarc.” November 28. http://www.(link is external)

thedailybangladesh.com/2014/11/27/handshake-signatures-salvage-saarc/(link is external)

106 Hockenos, Paul. 2014. “Germany’s Revolution in Small Batch: Artisanal

Energy.” FP. October 31. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2014/10/31/german_green_energy_revolution_backyard_windmills_solar_gas(link is external)

Breyer et al. 2014. “North-East Asian Super Grid: Renewable Energy Mix and Economics.” 6th World

Conference of Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC-6). November 24 – 27. Kyoto, Japan.

Red Ferret. 2014. “Nissan Leaf To Home – your electric car as emergency home generator.” June 23.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zd-crZIHWYM(link is external)

Onlycars. 2014. “Nissan Launched Leaf to Home V2H EV Power Supply System.” July 14. https://www.(link is external)

youtube.com/watch?v=roXasxxuViA(link is external)

107 Reuters. 2015. “South Korea launches world’s second-biggest carbon market.” January 12. http://in.reuters.com/article/2015/01/12/southkorea-carbontrading-idINKBN0KL05K20150112(link is external)

International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development. 2014. China confirms 2016

national carbon market plans. November 27. http://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/biores/news/china-confirms-2016-national-carbon-market-plans(link is external)

World Bank. 2014. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing: Emission trading regime will start in January 2015

in South Korea. An Emission trading scheme is under consideration in Japan and Thailand.

IETA. 2013. “Kazakhstan: The World’s Carbon Markets: A Case Study Guide to Emissions Trading.”

September. http://www.ieta.org/assets/Reports/EmissionsTradingAroundTheWorld/edf_ieta_kazakhstan_case_study_september_2013.pdf(link is external)

World Bank. 2014. “Putting a Price on Carbon with a Tax.” http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/(link is external)

Worldbank/document/SDN/background-note_carbon-tax.pdf(link is external)

Revenue (estimated at ¥262.3 billion per year) is used to strengthen renewable energy and energy saving

measures.

108 World Bank. 2014. State & Trends Report Charts Global Growth of Carbon Pricing. May 28. http://www.(link is external)

worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2014/05/28/state-trends-report-tracks-global-growth-carbon-pricing(link is external)

109 WTO. 2014. Joint Statement regarding the launch of the environmental goods agreement negotiations.

July. http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/topics-domaines/env/(link is external)

plurilateral.aspx?lang=eng(link is external)

110 Page, Jeremy. 2014. “China Sees Itself at Center of New Asian Order.” The Wall Street Journal.

November 9. http://www.wsj.com/articles/ chinas-new-trade-routes-center-it-on-geopoliticalmap-(link is external)

1415559290(link is external)

Reuters. 2014. “China to establish $40 Billion Silk Road infrastructure fund.” November 8. http://www.(link is external)

reuters.com/article/2014/11/08/us-china-diplomacy-idUSKBN0IS0BQ20141108(link is external)

The Indian Express. 2014. “Infrastructure Investment Bank.” October 24. http://indianexpress.com/article/(link is external)

business/economy/india-20-others-set-up-asian-infrastructure-investment-bank/(link is external)

111 Emerson, David. 2013. “Comfortable Canada: But for how long?” Policy Options. July-August.

http://policyoptions.irpp.org/issues/summer-reading/emerson/(link is external)

Kelsey, Jane. 2013. “US-China Relations and the Geopolitics of the Trans Pacific Partnership

Agreements (TPPA).” Global Research. November. http://www.globalresearch.ca/(link is external)

us-china-relations-and-the-geopolitics-of-the-trans-pacific-partnership-agreement-tppa/5357504(link is external)

Solis, Mireya. 2014. “China flexes its muscles at APEC with the revival of FTAAP.”

East Asia Forum. November 23. http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2014/11/23/(link is external)

china-flexes-its-muscles-at-apec-with-the-revival-of-ftaap/(link is external)

Tellis, Ashley, Abraham Denmark, and Travis Tanner (eds.). 2013. Asia in the Second Nuclear Age

(Washington, D.C., National Bureau of Asian Research). http://carnegieendowment.org/files/(link is external)

SA13_Tellis.pdf(link is external)

Cronin, Patrick et al. 2013. The Emerging Asia Power Web: The Rise of Bilateral Intra-Asian Security Ties,

Center for New American Security. June 10. http://www.cnas.org/publications/emerging-asia-powerweb#.(link is external)

VI8-CyvF_h4(link is external)

Panda, Ankit. 2014. “China creates new ‘Asia for Asians’ security forum.” The Diplomat. September 15.

http://thediplomat.com/2014/09/china-creates-new-asia-for-asians-security-forum/(link is external)

Chin, Curtis. 2014. “Xi Jinping’s ‘Asia for Asians’ Mantra Evokes Imperial Japan.” South China

Morning Post. July 14. http://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1553414/(link is external)

xi-jinpings-asia-asians-mantra-evokes-imperial-japan(link is external)

“New Asian security concept for new progress in security cooperation.” Full Text of Chinese President Xi

Jinping’s speech delivered at the Fourth Summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building

Measures in Asia (May 21, 2014). Chinese Foreign Ministry. May 28, 2014. http://www.china.org.cn/(link is external)

world/2014-05/28/content_32511846_2.htm(link is external)

The Telegraph. 2015. “Britain’s plan to join China’s ‘World Bank’ angers Washington.” March 12.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/11468997/Britains-plan-to-join-(link is external)

Chinas-World-Bank-angers-Washington.html(link is external)

Lawrence H. Summers. 2015. “Time US leadership woke up to new economic era.” April 5.

http://larrysummers.com/2015/04/05/time-us-leadership-woke-up-to-new-economic-era/(link is external)

112 Jong-Wha, Lee. 2014. “China’s new world order.” Economia. November 13. http://economia.icaew.(link is external)

com/opinion/november-2014/chinas-new-world-order(link is external)

Glaser, Bonnie. 2014. “Notes from the Xiangshen Forum.” Center for Strategic & International

Studies: Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. November 25. http://amti.csis.org/(link is external)

notes-from-the-xianshang-forum/(link is external)

The Economist. 2014. “Why China is creating a new ‘World Bank’ for Asia.” November 11. http://www.(link is external)

economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/11/economist-explains-6(link is external)

Parameswaran, Prashanth. 2014. “The truth about China’s ‘Big, Bad’ infrastructure bank.” The Diplomat.

October 16. http://thediplomat.com/2014/10/the-truth-about-chinas-big-bad-infrastructure-bank/(link is external)

Desker, Barry. 2013. “Why the world must listen more carefully to Asia’s rising powers.” Europe’s World.

February 1. http://europesworld.org/2013/02/01/why-the-world-must-listen-more-carefully-to-asiasrising-(link is external)

powers/#.VIC_yjHF98E(link is external)

Werth, Matthew. 2013. “Effects of Collectivist vs. Individualist Approaches to Ethics on Sino-US

Relations.” Global Ethics Network. April 29. http://www.globalethicsnetwork.org/profiles/blogs/(link is external)

collectivist-vs-individualist-approaches-to-ethics-their-effects(link is external)

Vanoverbeke, Dimitri and Michael Reiterer. 2014. “ASEAN’s Regional Approach to Human Rights: The

Limits of the European Model?” in European Yearbook on Human Rights 2014. p. 188. http://tembusu.(link is external)

nus.edu.sg/docs/ASEANHR2014.pdf(link is external)

113 Business Insider. “The US is losing its cyber edge and ‘a black swan event’ is increasingly likely”. May 8,

2015. http://www.businessinsider.com/bremmer-and-cyberwarfare-2015-5#ixzz3ZwAcqxrY(link is external)

Ian Bremer, “Proliferation [of cyber technology] is occurring exponentially faster [than traditional military

technology], meaning that response strategies are reactive and underdeveloped, that in turn leads to

strategic surprise from the United States when the cyber capabilities of enemies are deployed.”

114 United Nations. 2014. “An International Code of Conduct for Information Security: China’s perspective

on building a peaceful, secure, open and cooperative cyberspace.” Submission to the United Nations.