Foresight on AI: Policy considerations

Foreword

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly evolving, presenting both opportunities and challenges for Canada. As AI continues to advance, it is crucial to understand its potential impacts on governance, society, and the economy.

Policy Horizons Canada (Policy Horizons) is dedicated to exploring how AI might shape our future. By engaging with a diverse range of partners and stakeholders, we aim to identify key areas of change and support policy and decision-makers as they navigate this dynamic landscape.

On behalf of Policy Horizons, I extend my gratitude to everyone who has shared their time, knowledge, and insights with us.

We hope you find this report thought-provoking and valuable.

Kristel Van der Elst

Director General

Policy Horizons Canada

Introduction

This Foresight on AI report complements numerous reflections on AI futures across the Government of Canada. It aims to support decision makers – involved either in AI implementation or in policy setting related to AI – by exploring factors that could shape the evolution of AI, in terms of technical capabilities, adoption, and use, and which might be “beyond the horizon.” The report does not provide specific policy guidance and is not meant to predict the future. Its purpose is to support forward-looking thinking and inform decision making.

As part of this work, Policy Horizons has done a literature review, researched ongoing development related to the field, engaged with policy analysts and decision makers internal to the government, and held extensive conversations with key AI experts.

The 16 insights captured in this report explore future possible capabilities of AI, longer-term risks and opportunities, and uncertainties related to policy-relevant assumptions. Readers can seek to understand the impacts AI could have on governance, society, and the economy. When engaging with this report, readers are invited to ask:

- How will future advancements in hardware, software, and interfaces create new opportunities and risks for Canada and its allies

- Where could AI bring the biggest and most unexpected disruptions to governance, society, and markets

- What assumptions about AI’s development and deployment in the future may need to be challenged or further explored before they form the basis for decision making

The 16 insights are synthesised in 16 insights about factors shaping the future of and with AI and expanded upon further in the document.

Defining AI

There are many ways to define artificial intelligence, along with much debate about whether or not the term should even continue to be used.Footnote 1, Footnote 2, Footnote 3 For the purpose of this work, Policy Horizons Canada uses the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) definition of an AI system as “…a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.”Footnote 4

16 insights about factors shaping the future of and with AI

- AI could break the internet as we currently know it

Emerging AI tools have the potential to undermine the advertising business model that has served as the foundation for the internet for much of the last 20 years. The internet in the age of AI could be very different, one where people have more agency and control, but which is also less useful and secure.

- AI could empower non-state actors and overwhelm security organizations

In the future, more accessible and versatile AI will have implications for security. Non-state actors — friendly and hostile — will have access to capabilities traditionally held only by states. They might be able to deploy them faster than states, keeping security organizations in a constant race to catch up.

- Lack of trust in AI could impede its adoption

How trust in AI will evolve is unknown. Frequent or unaddressed failures in AI systems — or one significant failure — could erode trust and impede adoption, jeopardizing entire industries. Emerging forms of certification, verification, and efforts to rectify harms could encourage user trust and uptake.

- Bias in AI systems could remain forever

Bias is a feature of both human and AI decision making. As the data used to train AI is often biased in hard-to-fix ways, growing reliance on AI in decision-making systems could spread bias and lead to significant harm. Bias may never be eliminated, in part due to conflicting perspectives on fairness.

- Using AI to predict human behaviour may not work

While AI sometimes makes impressive predictions about human behaviour, many are inaccurate. Basing decisions on these predictions can have dire consequences for people. It might be impossible to improve the technology to a level where its benefits outweigh the costs.

- AI could become “lighter” and run on commonly held devices

Rather than a few large AI models running on cloud-based supercomputers, future AI models could be diverse and customized, some of them running on small, local devices such as smartphones. This could make regulation and control more complicated and multiply cybersecurity risks.

- AI-driven smart environments everywhere

Many products could be sold with AI as a default, creating ‘smart’ environments that can learn and evolve to adapt to the needs of owners and users. It may be difficult for people to understand the capabilities of smart environments, or to opt out of them.

- AI further erodes privacy

As AI-enabled devices collect more data online and in real life, efforts to turn data into new revenue streams could butt up against more privacy-conscious attitudes and devices. A new status quo may emerge that looks very different from the opaque way that users today exchange their data for free services.

- Data collected about children could reshape their lives in the present and future

Jurisdictions are expressing concerns about children’s privacy as AI technologies become more ubiquitous. Pervasive data collection in childhood could offer new opportunities for accessibility and education, but also worsen existing vulnerabilities, erode privacy, and reshape adult lives in the future.

- AI could reshape our ways of relating to others

AI tools could mediate more social interactions — in public or professional settings, or in private with friends, family or romantic partners. These tools could be used to flag suspicious or harmful behaviour, and help avoid social blunders — but they could also assist in manipulating and preying on others.

- AI could delay the green transition

AI uptake is driving up demand for energy and water globally. This could potentially delay the green transition, though Canada could benefit from an increased demand for greener data centres.

- AI could become more reliable and transparent

In the future, AI could have improved reasoning skills, allowing it to produce better analyses, make fewer factual errors, and be more transparent. However, these improvements may not be enough to overcome problems related to bad data.

- AI agents could act as a personal assistant with minimal guidance

In the future, people could have a general-purpose AI agent acting as a personal assistant, capable of performing multi-step tasks for its user, 24/7. Impacts could include improved access to task automation, greater productivity, disruption of advertising-based business models, and unforeseen harms.

- AI in Assessments and Evaluations

AI is disrupting established assessment and evaluation processes, such as job screenings, grant application evaluations, peer review, and grading. Screening processes could see a significant increase in applicants, and new forms of evaluation could emerge that focus less on written work as a measure of competence.

- AI and neurotechnology

AI-powered neurotechnologies are allowing people to monitor and manipulate the activities of their brain and nervous system. Further developments could bring major advances in health and wellness, but also raise significant privacy, ethical, and social concerns.

- AI could accelerate the development and deployment of robots

Improving AI and falling costs are allowing “service robots” to proliferate outside of industrial contexts. AI companies are developing humanoid robots with a wide range of cognitive and physical capabilities, bringing change to white- and blue-collar jobs.

Insight 1: AI could break the internet as we currently know it

Alternative format

(PDF format, 8.4 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-211/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76881-6

Emerging AI tools have the potential to undermine the advertising business model that has served as the foundation for the internet for much of the last 20 years. The internet in the age of AI could be very different, one where people have more agency and control, but which is also less useful and secure.

Today

The internet is an integral part of Canadians’ everyday lives. Young people, in particular, rely on it as a source of friendshipsFootnote 5 and information.Footnote 6 Across the wider population, 95% of Canadians over the age of 15 use the internetFootnote 7 and 75% engage in online bankingFootnote 8 and shopping.Footnote 9 Nearly half of all households have internet-enabled smart devices.Footnote 10

While more websites exist than ever before, most people’s experience of the internet is dominated by a small handful of massive companies. As an online joke puts it, “the internet is 5 giant websites showing screenshots and text from the other 4.”Footnote 11 Today, 65% of all internet traffic is to domains owned by Alphabet, Meta, Netflix, Microsoft, Tik Tok, Apple, Amazon, or Disney.Footnote 12 Google accounts for 91% of all internet searches.Footnote 13

Advertising funds the provision of free online services and the online creator economy.Footnote 14 Alphabet, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon each earn billions from online advertising.Footnote 15 Companies invested US$46.7 billion in 2021 in optimizing their website design to rank more favourably on search engines, get more traffic, and generate more ad revenue.Footnote 16

AI-generated content is rapidly becoming more realistic and human-like. Until recently, most online content was human-generated as computer-generated content was of generally low quality. This began to change in 2022 with the release of Dall-E 2, Midjourney, and ChatGPT. Large language models (LLMs) can produce high-quality human-like text. AI image generators can produce photorealistic images. AI video generators are advanced enough to interest Hollywood.Footnote 17 Voice generators have made popular AI song covers.Footnote 18 While most AI-generated content can still be identified through subtle telltale signs, it is becoming harder to distinguish from human-made content.

AI is not yet playing a significant role in undermining cybersecurity, but incidents are increasing. 70% of Canadians reported a cybersecurity incident in 2022, up from 58% in 2020. Although these are still mostly unsophisticated spam and phishing attempts,Footnote 19 fraud cases involving deepfakes increased 477% in 2022.Footnote 20 Scammers have started to make fake ransom calls using AI-generated voices of the target’s loved ones.Footnote 21 Deepfake-related institutional fraud cases are also emerging, leading to millions of dollars in potential losses for firms and governments.Footnote 22

Futures

AI-powered agents and search engines could transform how people interact with the internet. Instead of users going to specific websites, AI tools could create custom, personalized interfaces that are populated with content from across the internet. They could also help users find niche content and communities beyond major social media platforms.

These tools could disrupt internet ad-based business models. Should a significant portion of web traffic be made up of AI bots pulling information for their users, websites and search engines may earn less revenue from showing ads. They may need to find other ways of generating money, such as introducing subscriptions, paywalls, or the direct monetization of user data.

The internet could become dominated by AI-generated content, which may be indistinguishable from human-generated content. Online platforms could create multimedia content tailored to individual users. The internet could be awash with AI-generated websites filled with spam, misinformation, bots, and fake product reviews. It could become difficult for users to differentiate quality content from junk. If AI factchecking does not improve, this could become even more challenging.

The general sense of trust and security that Canadians feel online could be greatly diminished. When video calls can be convincingly deepfaked, it could be challenging for a person to know if a new online friend is a real person or an AI phishing scam. AI-powered disinformation campaigns could become more sophisticated, further undermining trust in institutions. As AI tools become more accessible and powerful, anyone with even the tiniest online presence could be exposed to a growing risk of harm.

Implications

- AI Search engines may be held accountable for results that are displayed to users. This could have legal repercussions and damage trust particularly if results are erroneous and even dangerous

- Content and services that were once free may be put behind paywalls as AI tools undermine the online advertising business model

- Websites may attempt to directly monetize user data and content, for example by licensing it as training material to AI companies

- Sponsored content, product placement, and other forms of advertising may become more common

- While human-generated content is unlikely to disappear, content creators may struggle to compete with cheap and tailored AI-generated content

- Content creators may feel more pressure to monetize their audiences

- Human taste and curation could become highly valued. Content creators may give way to content curators, who amass followings based on their curation of online content

- Unique, personalized content could lead people to feel isolated with fewer cultural touchpoints

- AI tools may shift control of the design, layout, and experience of a website from web designers to users. This could make it easier for users to avoid the addictive or manipulative designs known as “dark patterns”

- Navigating the internet without AI tools could become very difficult

- Websites may cease to exist as they are currently known, instead becoming repositories of data to be scraped by AI. Businesses may no longer need web designers

- Distrust could be the prevailing attitude online as cybersecurity risks increase and AI-generated content dominates the internet

- AI phishing schemes could become more sophisticated

- People may become more selective with what information they share online

- New authentication measures may emerge in attempts to restore trust online

- If trust in AI continues to decline (see Insight 3), people may fear they are being manipulated by AI-tailored feeds of content

- If search engines cannot effectively sort quality content from AI spam, they may no longer be effective go-to sources for all queries

- People may rely on a few trusted sources for information online

- Existing models of e-commerce may be disrupted in unforeseen ways

Insight 2: AI could empower non-state actors and overwhelm security organizations

Alternative format

(PDF format, 3.6 KB, 4 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-212/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76883-0

In the future, more accessible and versatile AI will have implications for security. Non-state actors — friendly and hostile will have access to capabilities traditionally held only by states. They might be able to deploy them faster than states, keeping security organizations in a constant race to catch up.

Today

AI is lowering barriers to entry and reducing the cost of conducting attacks.Footnote 23 For example, AI can help someone with limited programming skills write malicious software.Footnote 24 Leading open-source AI models only have marginally less capabilities than what is currently considered the most powerful general-purpose AI, GTP-4 Turbo.Footnote 25 Their general-purpose nature makes them equally useful to all types of problems, including harmful activities. It is uncertain who will use AI more effectively and quickly — government bodies among rival nations or non-state actors.Footnote 26 However, AI could empower non-state threat actors, corporations, or nations who are not bound by legal or ethical constraints, and willing to apply the technology in ways other states cannot.

Futures

Many new actors could access large-scale monitoring in the future. AI’s ability to analyze large amounts of open-source data could provide new actors with the ability to track and predict the movement of police and military forces.Footnote 27 AI tools can help write malicious computer code, making cyber defence more difficult. Similarly, ChatGPT has been used to create evolving malware, malicious software that can change its original code to evade cyber defences.Footnote 28

AI can also be used in unconventional attacks, to lower the cost of inflicting physical harm or attacking infrastructure. For example, AI can facilitate the process of 3D printing dangerous parts like those needed to make nuclear weapons.Footnote 29 AI could also be used to automate swarms of low-cost drones to overwhelm air defences,Footnote 30 providing an advantage to smaller actors who wish to target urban settings or confront modern militaries. Should AI greatly increase access and automate harm, this could increase pressure on the security sector and change how it keeps citizens safe.

Implications

- Open-source AI could empower non-state threat actors with new tools and erode advantages traditionally held by states, such as surveillance and monitoring Footnote 31

- There may be constraints of the ability of law enforcement agencies to gather intelligence as compared to non-state actors

- More communities could challenge the use of AI by law enforcement agencies

- Innovative use of AI could surpass the ability of defence and security organizations to adapt. Failures in public safety could weaken institutional trust or change public attitudes on appropriate government use of AI Footnote 32

- Private AI firms could become the main players in the cybersecurity and intelligence sectors, including in spaces traditionally seen as within the public domain

Insight 3: Lack of trust in AI could impede its adoption

Alternative format

(PDF format, 3.4 KB, 6 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-213/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76885-4

How trust in AI will evolve is complicated and unknown. Frequent or unaddressed failures in AI systems — or one significant failure — could erode trust and impede adoption, jeopardizing businesses that depend on AI. Emerging forms of certification, verification, and efforts to rectify harms could encourage user trust and uptake.

Today

Trust is central to acceptance of AI and, in Canada, trust in AI is declining.Footnote 33 The CanTrust index shows that Canadians’ trust in AI declined by 6% between 2018 and 2024.Footnote 34 The global IPSOS AI Monitor shows that the Anglosphere, including Canada, has less trust in AI than other regions: for example, 63% of Canadians are nervous about products and services that use AI compared to only 25% of people in Japan.Footnote 35

Trust in AI depends on the context in which it is used. For example, trust is highest for simple tasks such as adjusting a thermostat, and lower for tasks connected to personal safety such as self-driving cars.Footnote 36 Public trust in self-driving cars is low and falling. In 2023, only 22% of Canadians reported trusting self-driving cars and other AI-based driverless transportationFootnote 37 — compared to 37% of Americans, which is down from 39% in 2022 and 41% in 2021.Footnote 38

Despite declining trust, use of AI tools in Canada is growing. A 2024 Leger poll found that 30% of Canadians now use AI, up from 25% a year ago. Younger demographics are using AI more than older demographics — 50% of those 18-35 report using AI, compared to only 13% of those 55 and older.Footnote 39

Risks and failures arising from AI technologies have captured public attention frequently over the past year. In some instances, finetuning and testing of many AI tools was done after public roll out, which stands in stark contrast to trials for clinical drugs which require long periods of testing before release to the public. New initiatives to capture and report on AI incidents have emerged, such as the AI Incident Database and the OECD AI Incidents Monitor.Footnote 40, Footnote 41

Adoption of AI can feel forced, rather than chosen through personal agency. The current push to integrate AI everywhere can mean that valid concerns around data security, fairness, environmental consequences, and job security are downplayed.Footnote 42 Forcing people to adopt AI in their everyday lives without also making efforts to make the technology more trustworthy can limit the potential transformational impacts of the technology.Footnote 43 The current backlash against the increasing use of AI facial recognition technology in airports is one example of the interplay between forced adaptation in the absence of trust.Footnote 44

Futures

Improvements in technology, practices and systems could help to build trust in AI. For example, new capabilities such as neuro-symbolic AI, which combines neural networks with rules-based symbolic processing, promise to improve the transparency and explainability of AI models. Firms’ adoption of new labelling, certification, or insurance models could offset some of the mistrust in AI.Footnote 45, Footnote 46 And some providers are now developing ways to assess AI models for safety and trustworthiness, offering warranties to verify their performance.Footnote 47, Footnote 48 In the future, AI systems could give a confidence interval for everything from search results to self-driving vehicles, supporting users in weighing the risks and uncertainties involved.Footnote 49

More strategic and thoughtful deployment of AI could enhance trust. In the future, AI will likely become the right solution to some problems but not others. Trust in AI could be enhanced if people perceive that it is making their lives easier,Footnote 50 rather than replacing tasks they enjoy or seeming like a solution in search of a problem. Individual familiarity with AI may build trust in one area of work or life, without necessarily translating to increased levels of trust in the overall AI ecosystem.Footnote 51

High-profile failures and growing appreciation of risks could erode trust. Skepticism and mistrust could grow as the risks of AI become more well known and well documented and as more high impact tasks are delegated to AI. Groups that are negatively impacted by AI are actively opposing its use in some domains, such as writers and artists who are collectively organizing to limit what they see as the destructive power of the technology.Footnote 52 Mistrust could be driven not only by narratives that describe AI as an extinction-level threat, but also by its association with growing inequality.Footnote 53 Similarly, high-profile technological failures could cast shadows of mistrust into the future. For example, public trust and support for nuclear power in Canada declined significantly in the wake of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in 2011, and public concerns over nuclear safety hindered the sector’s growth for years.Footnote 54 A similar loss of trust in AI technologies such as self-driving cars, could jeopardize not just one company, but entire industries.

Implications

- Lack of trust could be a major impediment to the integration of AI in some sectors

- A single high-profile outlier incident involving an established AI system could disproportionately harm trust in and uptake of AI — for example, a financial crisis triggered by AI-generated content and high-frequency algorithmic trading

- People could trust AI to perform certain tasks more than they trust other humans

- Differing levels of trust in AI across groups or use cases could unite people across typical societal divisions or polarize them in new ways

- Excessive trust in some AI outputs could increase misinformation and disinformation, with consequences for democracy and societal cohesion

- A poor experience with one AI system could lead to distrust in other AI systems, while a positive experience with one AI tool could lead to increased trust in other AI applications

- Case law and legislation that determines accountability for decisions taken by or with AI could influence trust and adoption

- The emergence of new labels and certifications could affect consumer confidence in AI, such as warning labels, or those analogous to fair trade or organic produce labelsFootnote 55

- Accountability and responsibility regimes will be clarified, and many systems will need to determine who is accountable for the failures of AI

Insight 4: Bias in AI systems could remain forever

Alternative format

(PDF format, 5.7 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-214/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76887-8

Bias is a feature of both human and AI decision making. As the data used to train AI is often biased in hard-to-fix ways, growing reliance on AI in decision making systems could spread bias and lead to significant harm. Bias may never be eliminated, in part due to conflicting perspectives on fairness.

Today

Bias in AI is seen as a major issue capable of automating discrimination at scale in ways that can be difficult to identify. While human decisions are also biased, one of the major risks of automating high-stakes decisions is that these become more widespread and less detectable, increasing the possibility of systemic errors and harms. While a single biased manager could decide to give higher interview scores to the few job applicants that look and speak like them, a biased AI model could have a similar effect on potentially thousands of people across organizations, sectors, or countries.

Many AI products claim to be less biased than human decision makers but independent investigations have revealed systematic failures and rejections. Footnote 56 For example, an audit of 2 AI hiring tools found that the personality types it predicted varied depending on whether an applicant submitted their CV in Word or raw text.Footnote 57 Similar tools have discriminated against womenFootnote 58 or people with disabilities.Footnote 59 Bias is embedded in AI in many parts of its lifecycle — training data, algorithmic development, user interaction, and feedback.Footnote 60

Bias may be impossible to eliminate because the data used for training AI models is itself often biased in ways that cannot easily be fixed. Controlling results can also cause problems. For example, an AI model that learns to discard racially sensitive wording might omit important information about the Holocaust or slavery.Footnote 61 Further, algorithms often cannot compute different notions of fairness at the same time, leading to constantly different results for certain groups.Footnote 62, Footnote 63, Footnote 64

Futures

In a future where bias can never be eliminated — whether human or algorithmic — societies may need to rethink current ideas about fairness and how to best achieve it. People do not necessarily agree on the meaning of “fair.” For example, some consider affirmative action to be fair while others do not. Institutions could adopt standards intended to distribute resources — jobs, grants, awards, or other goods — in ways that explicitly attempt to repair historical injustices. Organizations seeking to avoid systemic bias may use an “algorithmic pluralism” approach, which involves various elements in the decision-making process and ensures no algorithms severely limit opportunity. Footnote 65

Efforts could be made to reduce bias in AI systems to an acceptable level, though eliminating it entirely could be impossible. Pushback may continue against using AI technologies in certain sensitive domains, such as policing or hiring. Alternatively, these technologies could continue to improve and become less biased in the future. Either way, there will likely be a continued push to reducing bias in AI technologies.

Implications

- Systemic harms or failures could become institutionalized in contexts where single algorithms are allowed to make bulk decisions about people’s access to certain resources (e.g. jobs, loans, visas)

- Human biases could become greater among those who use AI systems, as people learn from and replicate skewed AI perspectives, carrying bias with them beyond their interactions

- Disagreements about the best ways to code for algorithmic fairness may result from different definitions of what fairness actually means. This could lead to completely different results for similar technologies or systems

- The inability to eliminate bias from algorithms could ultimately lead to political, social, or economic divisions

- If decisions become more distributed, including various algorithms and humans at different points in a process, it could be difficult to make discrimination claims or identify a responsible party for discrimination

- High-profile cases of algorithmic discrimination could lead to loss of trust in AI decision-making systems, particularly in policing and healthcare, and an increase in litigation

Insight 5: Using AI to predict human behaviour may not work

Alternative format

(PDF format, 6.6 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-215/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76889-2

While AI sometimes makes impressive predictions about human behaviour, many are inaccurate. Basing decisions on these predictions can have dire consequences for people. It might be impossible to improve the technology to a level where its benefits outweigh the costs.

Today

More governments and institutions are using AI to predict human behaviour and make decisions about individuals. For example, more than 500 schools in the U.S. use an AI model called Navigate to predict student success.Footnote 66 Social workers in the U.S. have used AI to predict which child welfare calls need further investigation.Footnote 67 Both are examples of “predictive optimization”.Footnote 68 Notable AI engineers have argued that predictive optimization algorithms are based on faulty science, with AI predictions being only slightly more accurate than the random flip of a coin.Footnote 69 Despite this, they continue to be used because they outsource complex work like developing decision-making rules (e.g. what criteria to investigate for fraudulent behaviour or how to decide if a child is at risk of abuse). Human-generated decision-making rules can appear subjective and inaccurate compared to those of predictive AI models, which claim to reflect objective patterns in the real world.

Box #1:

Predictive optimization

The use of AI to predict future outcomes based on historical data, to make decisions about individuals.

Predictive models are not always right. Predictive AI models are plagued by many issues, including errors due to a mismatch between training data and deployment data. Because predictive AI must be trained on past data, it cannot account for emergent and complex variables in the world and in individual human behaviours. Models may be unable to account for new and unexpected drivers. Moreover, AI cannot filter out the effects of racist real-world practices such as disproportionate policing in Black neighbourhoods or communities, which leads to increased false arrests.Footnote 70 This has led to inaccurate predictions for vulnerable people.Footnote 71

Predictive AI models cannot understand why real-world behaviour differs from their predictions. Models may assume that individuals will act rationally and consistently or follow the same rules and patterns of humans in aggregate. Models may not address the structural factors that account for differences between predicted and real-world behaviours. A focus on prediction may hinder the discovery of processes that can lead to new behaviours, such as when simplifying the language used on court summons reduced the rate of people failing to appear in court.Footnote 72

While sometimes justified based on cost savings, some governments have felt significant repercussions after using of predictive optimization models. For example, in 2021, the Dutch government resigned over a scandal involving the tax authority’s adoption of a self-learning AI to predict childcare benefits fraud.Footnote 73 The AI erroneously identified tens of thousands of families as owing excessive debts to the tax authority. Over 3,000 children were removed from their homes and many families remain separated. The scandal had significant repercussions, with families forced into debt, losing their homes, and some victims dying by suicide.

Futures

In the future, predictive optimization may be used in some jurisdictions but not others. It could be forbidden within some jurisdictions, particularly where governments have faced high costs and scrutiny due to failures. That could still allow the private sector to expand its currently opaque uses of predictive optimization.Footnote 74 Other jurisdictions may continue to use predictive optimization algorithms despite the risks. This could be because those affected are less able to pursue justice, or because their governments are not bound by democratic norms. Others may view predictive optimization as an inevitably imperfect tool, but one whose use can be justified due to cost savings. Institutions — including governments — that take up AI for predictive optimization and find that the costs outweigh the benefits could keep systems in operation far longer than they should or want to, due to the high amounts already invested or the difficulties involved in undoing a rollout. Some may see predictive AI as ethically unacceptable for decision-making, and instead work on interventions to minimize the predicted negative outcomes.

Implications

- Governments and companies that use predictive optimization without being transparent about the AI’s decision-making rules could be seen as untrustworthy

- If institutions use AI for predictive optimization while the burden of proof to contest inaccurate predictions is put on affected individuals, already vulnerable populations may face worsened outcomes. This could create new bureaucratic bottlenecks and tie up courts with algorithmic harms litigation, including cases related to human rights or Charter violations

- Attempts to sacrifice individual rights for collective gains may benefit privileged populations at the expense of the vulnerable, creating greater socio-economic divisions

- The uptake of predictive optimization models could create initial cost savings that quickly give way to new costs: to fight litigation from inaccurate predictions; to recontract providers to retrain and retune models; and to create new pathways for complaints and compensation for damages

- If AI decision-making pre-emptively punishes people based on biased assumptions, it could decrease the individual agency of vulnerable populations and place new obstacles in their life courses

Insight 6: AI could become “lighter” and run on commonly held devices

Alternative format

(PDF format, 3.1 KB, 4 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-216/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76891-5

Rather than a few large AI models running on cloud-based supercomputers, future AI models could be diverse and customized, some of them running on small, local devices such as smartphones. This could make regulation and control more complicated and multiply cybersecurity risks.

Today

Improvements in AI training and compression techniques are allowing smaller, less resource-intensive AI models to become more capable. The size of an AI model is often used as a shorthand for its power, capability, and quality. While the largest models are often the most powerful and capable, AI developers are releasing smaller, compressed versions derived from larger models. This allows the smaller model to retain most of the performance of the larger model while also allowing it to be much smaller, less energy demanding, and run on less powerful hardware.Footnote 75 This has led smaller, newer models to outperform older and larger models. For example, Phi-3, which was released in early 2024 and has only 3.8 billion parameters, has comparable performance to GPT-3.5, which was released in late 2022 with 175 billion parameters.Footnote 76 Companies including MetaFootnote 77 and MistralFootnote 78 have released open-source AI models that rival ChatGPT’s performance but can run on a laptop. Researchers in the field of TinyML are developing AI that is smaller and can run on less powerful devices to enable the “smart” Internet of Things (IoT). For example, the Raspberry Pi, a credit card-sized computer popular with programming and computer engineering enthusiasts, can now run a suite of AI models including facial recognition.Footnote 79

Box #2:

Model size

The size of an AI model is determined by how many parameters it has.

Parameters are variables in an AI system whose values are adjusted during training. Smaller models can have parameters numbering in the millions or fewer, while larger models can have more than 400 billion.

Futures

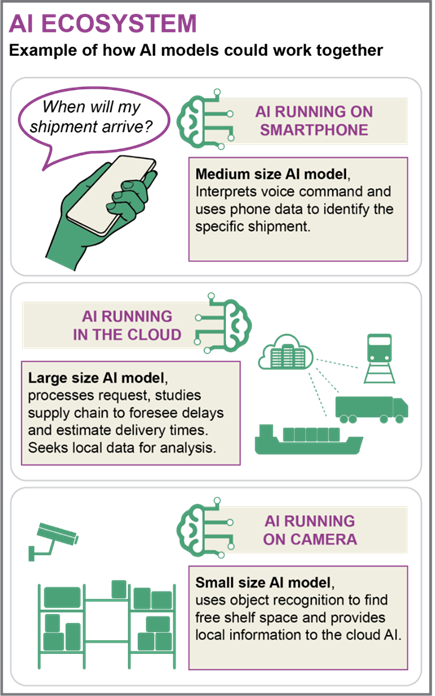

We may see thousands of different AI models capable of running locally on every type of digital device, from smartphones to tiny computers.Footnote 80 These models could be developed by amateurs, startups, or criminals. They could be based on open-source models and customised for different purposes through training on widely accessible datasets. For example, Venice AI is a web-based AI service, built from a handful of open-source AI models, that allows users to generate text, code, or images with little to no guardrails and is sold as ‘private and permissionless.’Footnote 81 As AI models of different sizes become more widely deployed, this may give rise to an ecosystem of AI models with various degrees of interoperability. Small models could interact with large, cloud-based, publicly accessible models, leveraging their power to perform tasks or learn (see Figure 1). Such small, localized models may lack safety measures and be deployed broadly without the knowledge of any authority.

Figure 1

Figure 1 AI Ecosystem, an example of how AI models could work together

Figure 1 – Text version

AI Ecosystem, an example of how AI models could work together

Figure 1 follows 3 AI models of various size working together along a supply chain. Each AI model has their own section. The first section depicts an AI running on a smartphone. Here a speech bubble says: ‘When will my shipment arrive?’ as someone asks the question to their AI running on a phone. The medium size AI model interprets voice commands and uses phone data to identify the specific shipment. The second section depicts an AI running in the cloud connecting different transportation vehicles. The large size AI model processes requests, studies the supply chain to foresee delays and estimate delivery times. It also seeks local data for analysis. The final section depicts an AI running on a surveillance camera in a warehouse. The small size AI model uses object recognition to find free shelf space and provides local information to the cloud AI.

Implications

- Regulations focused only on large AI models may not be effectiveFootnote 82

- Open-source AI could allow the circulation of models which are problematic, whether because they incorporate bias, lack safety measures, or facilitate illegal activitiesFootnote 83

- It could be hard to track bad actors training or running small but powerful AI models

- By analysing data locally, on-device AI models could help individuals protect their data and privacy

- Small businesses could customise their own AI tools to better meet their needsFootnote 84

- Compatibility between AI-enabled devices could provide users with more options but also create cybersecurity vulnerabilitiesFootnote 85

Insight 7: AI-driven smart environments everywhere

Alternative format

(PDF format, 3.8 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-217/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76893-9

Many products could be sold with AI as a default, creating “smart” environments that can learn and evolve to adapt to the needs of owners and users. It may be difficult for people to understand the capabilities of smart environments, or to opt out of them.

Today

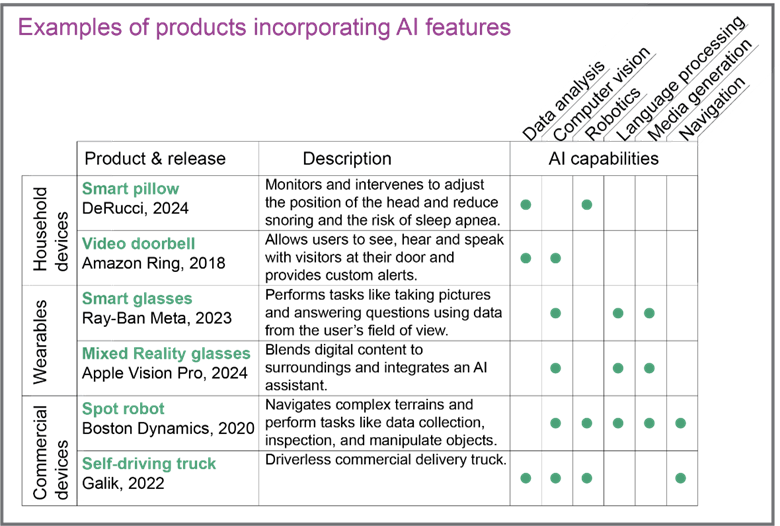

Autonomous devices and robots are increasingly present in our everyday lives. For example, restaurants are using robots to deliver meals.Footnote 86 Robot cleaners are commonly being used in commercial spaces.Footnote 87 In the agriculture sector, more autonomous and semi-autonomous machinery is being used to cultivate crops. In homes, AI is being added to everyday devices. Figure 2 shows further examples. Such devices could continue to gain new features as more capable AI models are released.Footnote 88

Figure 2

Figure 2 Examples of products incorporating AI features

Figure 2 – Text version

Examples of products incorporating AI features

Figure 2 is a table of different AI enabled products, their descriptions and the AI capabilities within each product. There are 3 product categories, each with 2 example products. The first, household devices, including a smart pillow and Amazon Ring the video doorbell. The second, wearables, including smart glasses and mixed reality glasses. And the third, commercial devices, including Spot the robot dog and a self-driving truck. Each of the 6 products are briefly described. For example, Smart pillow by DeRucci, released in 2024. Monitors and intervenes to adjust the position of the head and reduce snoring and the risk of sleep apnea. The table tracks which of 6 AI capabilities are included in each product. The capabilities are data analysis, computer vision, robotics, language processing, media generation, and navigation.

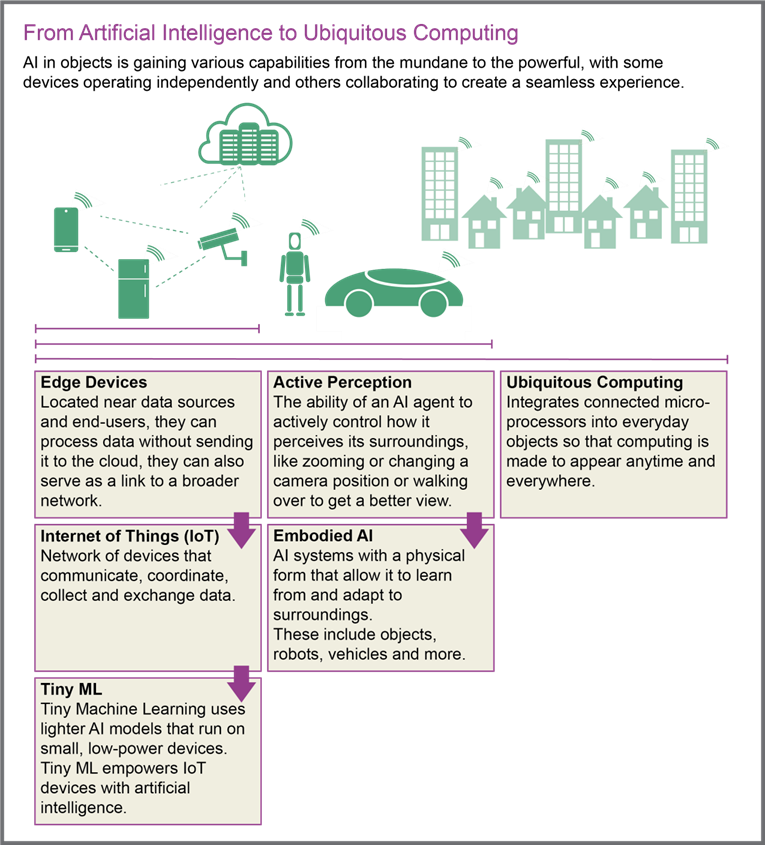

Researchers and industry may need more data about the physical world to train more advanced AI. AI that collects real-time information on its physical surroundings is referred to as embodied AI (see Figure 3).Footnote 89 AI can be embodied in anything from smart phones to household devices or human-like robots. When connected to sensors and given mobility, AI can interact with people and physical spaces, for example by opening doors or summoning elevators.Footnote 90 As giving AI a body can allow it to learn from interacting with the world much like humans do, it may represent a path toward developing more advanced AI.Footnote 91

Figure 3

Figure 3 From Artificial Intelligence to Ubiquitous Computing

Figure 3 – Text version

From Artificial Intelligence to Ubiquitous Computing

Figure 3 explores how AI in objects is gaining various capabilities from the mundane to the powerful, with some devices operating independently and others collaborating to create a seamless experience. These objects include smartphones, surveillance devices and appliances, as well as connected robots and self-driving cars. These devices in the image are connected via Internet of Things across the urban landscape. The figure provides the following definitions, each contributing to a final concept, Ubiquitous Computing: 1) Edge Devices are located near data sources and end-users, they can process data without sending it to the cloud, they can also serve as a link to a broader network. 2) Internet of Things is a network of devices that communicate, coordinate, collect and exchange data. 3) TinyML, or Tiny Machine Learning, uses lighter AI models that run on small, low-power devices. Tiny ML empowers IoT devices with artificial intelligence. 4) Active Perception is the ability of an AI agent to actively control how it perceives its surroundings, like zooming or changing a camera position or walking over to get a better view. 5) Embodied AI are systems with a physical form that allow it to learn from and adapt to surroundings. These include objects, robots, vehicles and more. 6) Ubiquitous Computing integrates connected microprocessors into everyday objects so that computing is made to appear anytime and everywhere.

It is becoming more difficult to understand the capabilities of devices in our surroundings. Some devices are referred to as ‘robots’ despite having no AI capabilities.Footnote 92 Other devices can have multiple AI functions. For example, tourists can rent AI-powered e-bikes that can give a guided city tour.Footnote 93 Bird watchers can buy AI-powered binoculars that identify wildlife.Footnote 94

Older devices can often be retrofitted with new capabilities in ways that are not obvious from the outside. For example, an AI kit can make an existing tractor fully autonomous.Footnote 95 Security cameras that have been in operation for a long time can be connected to facial recognition software.Footnote 96

Futures

In the future, more AI-powered devices may be found in more settings, from workplaces to leisure spaces and dwellings. It may become impossible to avoid interacting with these devices. The number of IoT (Internet of Things) devices could reach 75 billion by 2025, more than doubling in 4 yearsFootnote 97 and the global AI software market could grow roughly fivefoldFootnote 98 from 2022 to 2027.

Device manufacturers could be incentivized to add AI capabilities to more devices either as a selling feature or to collect data. Data can be useful not only to generate new revenue streams but also to train new models. This could be especially relevant if embodied AI proves useful in building next-generation frontier AI models, or if companies reach the limits of existing quality training data.Footnote 99 For example, by deploying a fleet of smart cars a company could use data on the city landscape, traffic, and the behaviour of pedestrians to train even more powerful AI models.

Everyday devices could end up having more powerful AI capabilities than needed. It may be easier to equip a device with an off-the-shelf, general-purpose AI, such as ChatGPT or Copilot, than to customize a model with more targeted functionality. Smart devices could become the default in new homes, ready to adapt to new owners or tenants. Devices could be sold with certain features locked behind a pay-for-access model, as was seen with the Amazon Ring,Footnote 100 and with Tesla,Footnote 101 and MercedesFootnote 102 cars.

General-purpose AI could become standard in a way that increasingly blurs the lines between consumer product categories. For example, smart watches and fitness trackers have raised concerns that they might occupy a regulatory grey zone between medical devices and low-stakes consumer products.Footnote 103 The Aqara home sensor can be used for everything from controlling lights to providing security surveillance or detecting falls.Footnote 104 The appearance of such objects may not clearly signal their capabilities. Human-like robots may have eyes that can see through walls, for example – or the same sensors could be entirely hidden.

Implications

- People could require new skills to navigate AI-powered spaces. Manufacturers may need to use new kinds of labelling or instructions to disclose the capabilities of their AI devices in a way that allows consumers to make informed decisions

- People unwilling or unable to engage with AI-powered spaces may find themselves unable to access certain services

- Insurance companies could encourage some kinds of AI monitoring or demand it as a condition of coverage.Footnote 105 For example, facial recognition to confirm the identity of a driver to reduce auto theft

- The rights and interests of individuals could come into conflict in new ways. For example, wearing smart glasses in public spaces or sending a robot to pick up groceries could challenge privacy rights. Trust is needed to ensure that the devices are not collecting the likeness of people without consent.Footnote 106 Property owners could install AI-powered devices to protect their investment or help with maintenance. Tenants may find themselves in a smart home with services they do not want or settings they cannot change

- Smart environments could change advertising strategies. It could become routine for AI-enabled devices to nudge users with personalized advertisements in real-time. For example, smart cars may reroute drivers towards certain businesses and encourage them to stop to make a purchase

Insight 8: AI further erodes privacy

Alternative format

(PDF format, 4.9 KB, 6 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-218/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76895-3

As AI-enabled devices collect more data online and in real life, efforts to turn data into new revenue streams could butt up against more privacy-conscious attitudes and devices. A new status quo may emerge that looks very different from the opaque way that users today exchange their data for free services.

Today

Advances in AI are exacerbating privacy issues with technology. Most Canadians have become accustomed to accessing free online services – such as social media sites, generative AI platforms, or mobile apps. In many cases, they unknowingly give consent to companies to collect their data, sell it to third parties, and use AI to make sense of it and draw inferences about them. For example, Facebook uses AI to make inferences about users’ suicide risk based on their social media posts.Footnote 107 Improvements in AI are allowing firms to analyze a greater variety and amount of data and transform it into revenue streams in new ways.

Not only online environments but also physical spaces are becoming less private. As noted in Insight 7, everyday household objects are outfitted with sensors to collect data – from toilets to toothbrushes to toys. Virtual Reality (VR) and video games can collect data about users’ behaviour in the home and use AI to make inferences about emotions and personality traits.Footnote 108 Outside the home, devices such as smart glassesFootnote 109 and AI pinsFootnote 110 are raising new questions about privacy in public. Fragments of human DNA, known as environmental DNA, collected from public spaces for purposes such as disease monitoring, can potentially be used to track individuals, illegally harvest genomes, and engage in hidden forms of genetic surveillance and analysis.Footnote 111, Footnote 112

Smart cars raise particular privacy concerns. In 2023 the Mozilla Foundation investigated 25 car brands and found that every one collected personal data that is not necessary to operate the vehicleFootnote 113, usually taken from mobile devices connected to cars via apps, this data can include a person’s annual income, immigration status, race, genetic information, sexual activity, photos, calendar, and to-do list. Of the 25 brands, 22 use this data to make inferences – for example, from location and phone contacts – and 21 share or sell data. Thirteen collect information about the weather, road surface conditions, traffic signs, and “other surroundings”, which can include passersby.Footnote 114 Ninety-five percent of new vehicles will be connected vehicles by 2030.Footnote 115

Futures

As the Internet of Things becomes the “AI of Things”, data may become even more valuable, further incentivizing ever more data extraction. It may become possible to draw more sophisticated inferences to predict human behaviour, movement, or identify individuals, as discussed in Insight 5.

However, international regulatory pushback could reshape the privacy landscape. More jurisdictions are passing and enforcing new data privacy lawsFootnote 116, such as the American Privacy Rights ActFootnote 117 in the US. This could change some, if not many, aspects of “surveillance capitalism”Footnote 118 by giving users more control over their data. Future legal reforms could reframe inferences as personal informationFootnote 119, making it more difficult to sell them to third parties.

Emerging technology could also shift the privacy balance. Edge computing, which refers to networks or devices that are physically near to the user, could enhance data privacy and security.Footnote 120 When user data is stored and processed on a user-owned device, it may be more difficult for companies to collect and sell it.Footnote 121 However, edge computing can also introduce new risks, such as enabling face recognition on local devices and potentially easier access for malicious actors.Footnote 122

Implications

- Distinctions such as public versus private and online versus offline could become increasingly blurred. Homes and other spaces could be experienced as more or less private depending on the use of devices. Visitors to homes and passengers in cars may demand new consent protocols to protect their privacy

- Data shared with third parties could lead to sensitive information being shared with insurance companiesFootnote 123

- Schools and childcare providers could use privacy protections as a competitive advantage to attract families

- Surveillance could change the practices of police and criminals

- Some forms of crime could move further underground and become more organized to evade detection

- New technological capabilities could create new opportunities for hacking, fraud, and stalking

- Traffic police may be less needed as monitoring of drivers by governments and insurance companies enables tickets to be issued automatically

- ActivistsFootnote 124 and journalistsFootnote 125 could increasingly use ubiquitous computing to “return the gaze” by collecting information about powerful organizations or individuals. This practice is known as “sousveillance” or “equivalence.” This could include hacking sensitive information about the personal lives of political representatives or other public figuresFootnote 126

- Data protection regimes could become more complex and less aligned globally

- Jurisdictions could struggle to balance privacy with researchers’ need for representative datasets in areas such as medicineFootnote 127

- Jurisdictions with weaker privacy laws could become increasingly “risky” destinations for work or travel

- Privacy-protecting devices could tilt the balance of power toward users

Insight 9: Data collected about children could reshape their lives in the present and future

Alternative format

(PDF format, 6.3 KB, 6 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-219/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76899-1

Jurisdictions are expressing concerns about children’s privacy as AI technologies become more ubiquitous. Pervasive data collection in childhood could offer new opportunities for accessibility and education, but also worsen existing vulnerabilities, erode privacy, and reshape adult lives in the future.

Today

Young people are a particularly vulnerable group with regard to data privacy.Footnote 128 Their sense of self and ability to make decisions are still developing. Healthy child development involves the ability to experiment and make mistakes without severe and lasting consequences. More jurisdictions are exploring how to protect children’s data and privacy rights and address challenges around meaningful consent.Footnote 129

Cases are growing of malicious actors using children’s data in ways that impact on their mental health and wellbeing. Critics point to how major tech companies capture attention and revenue through addictive user experiencesFootnote 130 and dark patterns.Footnote 131 Dark patterns are a type of web or app design that can be used to influence your decision making when you are using an app or navigating through a website – for example, by intentionally making it difficult to cancel a service.Footnote 132 Social media algorithms exacerbate issues related to negative body image.Footnote 133 Generative AI has been implicated in the circulationFootnote 134 and developmentFootnote 135 of child sexual abuse materials, both real and AI-generated, by adults and children.

Parents have extraordinary scope to both gain and offer visibility into their children’s private lives. For example, keylogger apps can let parents see not only messages a child sent, but also messages they typed but decided not to send.Footnote 136 Parents can also share their children’s private information with others. Some manage revenue-generating child influencer accounts that routinely share personal information and images of their children. These accounts are sometimes openly followed by pedophiles, who benefit from platform policies that reward engagement.Footnote 137

Unwanted “data” shadows could follow children into adulthood. Whether data is shared by parents or collected by platforms or devices,Footnote 138 it may create a “data shadow” that follows children throughout their lives.Footnote 139 This data shadow can begin before birth – for example, when parents use DNA testing services to learn about their children’s genetic susceptibility to diseases.Footnote 140 As these vast troves of data can be stored indefinitely, future AI systems could draw on them to make new inferences about individuals as they grow into adults.

Schools are collecting ever more information about students, using third-party software and AI analysis tools. Since the pandemic, use of student management apps has grown exponentially in daycares, elementary schools, and high schools in Canada. For example, an estimated 70% of elementary schools use Class Dojo. Its privacy policy states it may share data with third-party service providers including Facebook and Google.Footnote 141

Data breaches have affected children and youth in Canada and beyond. In 2024, school photos of 160 students in Alberta were stolen when hackers accessed the cloud storage provider of a school yearbook company.Footnote 142 Ransomware gangs have targeted US public schools, releasing sensitive student data on mental health, sexual assaults, and discrimination complaints.Footnote 143 In 2023, ransomware attacks affected institutions such as Toronto’s Sick Kids Hospital;Footnote 144 Family and Children’s Services of Lanark, Leeds and Grenville;Footnote 145 and Ontario’s Better Outcomes Registry & Network, in which 3.4 million health records were breached.Footnote 146

Corporations and NGOs hold a large amount of sensitive data about youth, which can be vulnerable to breach. Private parental control apps have been breached, exposing monitored children’s data.Footnote 147 In 2023, TikTokFootnote 148, MicrosoftFootnote 149, and AmazonFootnote 150 were fined for children’s privacy violations in various jurisdictions. As a non-governmental organization, Kids Help Phone – which holds the largest repository of youth mental health data in CanadaFootnote 151 – reports conducting a privacy impact assessmentFootnote 152 and aggregating and anonymizing its data.Footnote 153

Futures

The opaque sale, circulation, and analysis of children’s data will become more common, begin much earlier in life, and be put to unforeseen uses in the future. The number of data-collecting devices children interact with – at home, school, and beyond – will increase (see Insight 7 and Insight 8). Some of these devices could be more vulnerable to breaches of sensitive information.Footnote 154

AI-powered monitoring technologies could become more important, but could also be subverted. Parents could look to AI-powered monitoring technologies to help control their children’s online activities and gatekeep increasingly complex informational and media environments.Footnote 155 However, young people could also develop increasingly sophisticated means of evading parental control.

Children and youth could inhabit more highly personalized media environments. Entertainment content and advertising could increasingly be generated or curated by personalized AI companions. Sub- and fan cultures could become increasingly personalized and politicized. Feelings of social isolation could become more prevalent, as well as reduced social cohesion. Some young people may become disillusioned with invasive AI-powered technologies and opt to spend more time offline. However, given the pervasiveness of AI this might not be an option in the future.

The market for youth data may become more competitive as concerns around youth data privacy increase. This could lead tech companies to develop more insidious ways to extract and trade youth data. The age cut-off for being seen as a “child” could differ in different contexts. Data could have to be released when a child attains the age of majority.Footnote 156 Age verification technologies,Footnote 157 like those currently being used in some US states for pornography websites,Footnote 158 could be more widely used to protect youth from predatory adults and adult-only spaces.

Despite the many concerns they raise, new AI-enabled technologies could also collect data in ways that support accessibility.Footnote 159 They could be used to develop individualized learning tools that help students progress at their own pace. They could also enhance the quality of pediatric health care by assisting in diagnosis, patient monitoring, and precision medicine.Footnote 160

Implications

- Today’s children could face more frequent and devastating data breaches throughout their lives

- These breaches could result in forms of identity theft that lead to financial loss or the release of sensitive personal information

- Re-identification of anonymized personal data could become easier as data breaches become more routine and technologies advance – data that seems private today may not be tomorrow

- Lax restrictions could lead to data being used to make AI-mediated inferences about youth that affect their relationships and access to jobs, credit, or insurance in both childhood and adulthood

- Increased use of parental control technologies could lead to undue surveillance and loss of privacy and autonomy for children

- AI could make it more challenging for parents to identify problematic or harmful content, or easier for youth to conceal their engagement with it

- If awareness of issues related to children’s data privacy increases, more developers could be required to launch child-specific apps and platforms that are held to higher privacy standardsFootnote 161 or consider issues such as mental health and addiction

Insight 10: AI could reshape our ways of relating to others

Alternative format

(PDF format, 4.7 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-220/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76901-1

AI tools could mediate more social interactions—in public or professional settings, or in private with friends, family or romantic partners. These tools could be used to flag suspicious or harmful behaviour, and help avoid social blunders—but they could also assist in manipulating and preying on others.

Today

AI already plays a large role in mediating our relationships with strangers, friends, and family in online spaces. Recommender algorithms act as a social filter, determining which content a user sees, from which people, and in which order.Footnote 162 These algorithms can encourage users to engage with influencers and content creators who provide a high level of apparent access to their lives.Footnote 163 For some users, such “intimacies” can develop into parasocial relationships, where individuals feel emotionally connected or attached to total strangers.Footnote 164

AI devices mediate an increasing number of professional and personal interactions. For example, doctors are already using AI to help diagnose or monitor patients.Footnote 165 People are using AI to help write profilesFootnote 166 or messagesFootnote 167 on dating apps. AI can even analyze and flag the tone that individuals use in messages to one another, for example in apps used to mediate communication in difficult coparenting arrangements.Footnote 168

Wearable devices which introduce AI into new aspects of our lives can blur the lines between real and digital spaces. These devices can use virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and a combination of AR and VR known as mixed reality (MR).Footnote 169 Research suggests that immersive environments can be more emotionally impactful than traditional online spaces.Footnote 170 Collective experiences in VR can provide a new type of enriching social gathering for geographically distant groups. Harms in VR, such as assault, can have psychologically similar effects as the offline equivalent.Footnote 171

Individuals can develop emotional connections with AI companions. Millions are turning to AI companions to alleviate loneliness, access therapy, get advice, and for romantic connection.Footnote 172, Footnote 173, Footnote 174 When an AI model produces text, speech and images that are indistinguishable from those made by humans, it is easy to anthropomorphise the model by attributing motive and intent to its responses.Footnote 175

Users of popular platforms live in increasingly personalized and private worlds as AI curates the content they see. Social media algorithms often offer users content that suggests they “know” them better than even close friends might. Over time, however, consuming AI-curated content – as opposed to content shared by friends – may warp representations of the self.Footnote 176 As they scroll through content alone, users can enter what researchers call a trance-like state.Footnote 177

AI is changing how parents relate to and engage with their children. AI tools can allow parents an unprecedented level of visibility and control over the apps their children use, the content they consume, and the messages they write, as discussed in Insight 7. Smartphones or trackers can give parents real-time, 24/7 information about their children’s whereabouts.Footnote 178 These tools can erode children’s autonomy, privacy, and independence as they grow and mature. Similar tools used in romantic relationships can facilitate abusive behaviour and stalking.Footnote 179

Futures

In the future, AI could play a larger role in mediating professional interactions, limiting scope for forming new friendships. AI could improve the efficiency of communication between a company’s customers and employees and change workflows between individuals and teams. Workplace culture could become more impersonal, with fewer opportunities for socialising.

AI tools could also mediate more personal social interactions, even in the home among family members. Such tools could include AI agents, platform algorithms, or wearable devices, such as AR glasses. More information about and visibility into the inner lives of people, whether physiological or psychological, could become normalized. This could improve communication in relationships. It could also shift relationship dynamics in new ways, leading to lower trust and autonomy and more mental health issues.Footnote 180

Individuals could increasingly turn to AI for companionship or answers to personal problems. AI could help socially isolated individuals to connect with others.Footnote 181 AI therapists could provide tailored mental health care for populations that lack access: apps such as Black Female Therapist, for example, use AI trained to highlight the importance of systemic racism.Footnote 182 On the other hand, AI companions could further isolate individuals if they replace relationships with humans. Individuals who come to prefer synthetic relationships to real ones could end up disconnected from community, though not necessarily lonely.

Some individuals could seek human connection by sharing and comparing their media feeds. As media experiences become increasingly personalized, there could be increased interest in understanding the distinct worlds that people inhabit. This could include “feed analysis” in therapeutic settings, sharing feeds in the presence of friends, or even public feed-sharing events.Footnote 183

In the future, it may become impossible to distinguish between humans and hyper-realistic AI agents when interacting in online spaces. AI technology could be used to create digital replicas of deceased or estranged loved ones, or celebrities and influencers. AI agents could be perceived as exhibiting human emotions such as empathy and love. Individuals could have what feels like an intimate relationship with a person but is in fact a parasocial interaction with a chatbot. This could entirely replace human social connections for some vulnerable or lonely individuals.

Implications

- AI could help reduce inequalities for those who face language barriers or difficulties navigating complex social interactions

- Relationships with AI companions could feel indistinguishable from human connections, or even easier or better, for some people

- AI companions or therapists could have more influence on an individual’s behaviours than their family or close friends

- Social skills could atrophy. Skills such as listening and empathy could be eroded if users lean too heavily on AI assistance for social interactions or customize AI agents to reflect their needs and preferences

- Marriage rates could decline and loneliness could increase

- The experience of selfhood could change. Earlier and more frequent self-monitoring, and the application of predictive analytics to biological and mental processes, could lead to new ways of understanding and optimizing the self

- New forms of abuse and virtual crime could emerge, potentially challenging definitions of assault and harassment

- Predators could more easily gain the trust of children and adults, leading to greater risk of fraud, harassment, or other abuse

- Using AI tools to communicate with people could shift language over time, potentially towards greater homogenization and sterilization

- AI tools could flag suspicious behaviour, report abuse as it is happening, and help individuals navigate toxic or dangerous relationships

- Bullying and harassment could become more omnipresent and damaging to mental health if it occurs in realistic immersive environments or with the use of generative AI

Insight 11: AI could delay the green transition

Alternative format

(PDF format, 6.7 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-221/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76903-5

AI uptake is driving up demand for energy and water globally. This could potentially delay the green transition, though Canada could benefit from an increased demand for greener data centres.

Today

AI has climate impacts, though accurately measuring its carbon footprint is a challenge. Generative AI is a particularly energy- and water-intensive technology.Footnote 184 Training a new model consumes energy, as does the use of a model once trained. Google’s greenhouse gas emissions were 48% higher in 2023 than in 2019, due largely to the energy required by AI.Footnote 185 However, as AI companies are not all fully transparent about their energy use or environmental impacts from the development and disposal of hardware, it is hard to be sure about the carbon footprint of AIFootnote 186 Smaller models that run on devices, rather than in the cloud, could have fewer climate impacts (See Insight 6).

Data centres are already straining energy and water supplies. Machine learning models like ChatGPT process user queries in data centres.Footnote 187Footnote 188 Even in 2020 – before the take-off in generative AI – data centres and transmission networks produced 0.6% of total greenhouse gas emissions.Footnote 189 Data centres consume 10 to 50 times more energy per floor space than a typical commercial office building.Footnote 190 The largest in the world can use as much energy as 80,000 US households.Footnote 191 Polluting diesel generators provide backup power to most data centres during power outages.Footnote 192 Data centres also use water for evaporative cooling, and in warmer climates can use millions of gallons per day. With the computational power used by AI doubling roughly every 100 days,Footnote 193 demands on water and energy by data centres are increasing. Data centres in water-stressed regions of the U.S. have come under fire from local residents.Footnote 194 In some areas, plans to close coal-fired power plants have been delayed due to growing electricity demand from data centres.Footnote 195

Canada is an attractive destination for data centres. As AI use has grown, tech companies have sought to locate data centres in countries with cooler climates and clean and cheap power.Footnote 196 With its renewable hydroelectric power, Canada has become an attractive destination for tech companies looking to advertise a reduced carbon footprint.

Futures

Increased AI uptake could hinder the transition toward global climate commitments. As AI is integrated into more devices and processes, its energy and water use could rise steeply. For example, if every online search used ChatGPT, electricity demand would increase by an amount equivalent to adding 1.5 million residents to the European Union.Footnote 197 By 2026, AI could be using more power than the country of Iceland did in 2021.Footnote 198 The International Energy Agency has estimated that data centres’ electricity consumption could double between 2024 and 2026.Footnote 199 The market for GPUs (graphics processing units) used in data centres is projected to grow tenfold from 2022 to 2032.Footnote 200 IT seems poised to increase its carbon footprint in the coming decade, just as other industries are moving in the opposite direction.Footnote 201

Innovations in AI hardware and software could reduce energy use. Nvidia’s upcoming Blackwell GPUs for data centres, for example, promise to be much more efficient – offering up to 30 times the performance while consuming 1/25th of the energy of current chips.Footnote 202 There could also be a shift towards smaller, “lighter”, less energy-intensive computational modelsFootnote 203 (See Insight 6).

Canada could face challenges meeting AI’s demand for cheap, clean hydropower. Canadian utilities might find it challenging to meet the rapid growth in energy demand due to AI. Hydro Quebec anticipates that by 2032, data centres will contribute to an increase of about 2% of the total amount of electricity produced in Quebec in 2022.Footnote 204 Energy shortfalls are being projected in Quebec as early as 2027 and could be made worse by drought and other climate events.Footnote 205 Data centre providers could increasingly be asked to generate their own power and build their own energy infrastructure.Footnote 206

New ways to mitigate the energy demands and impacts of AI could scale up. Some AI companies, including Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, have announced plans to use nuclear energy to reduce their emissions.Footnote 207 In September 2024, Microsoft acquired Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear plant, closed since 2019. Microsoft plans to reopen the plant and purchase its entire electric generating capacity over the next 20 years.Footnote 208 Google is expected to have small modular nuclear reactors operational by 2030.Footnote 209 Waste heat from data centres could increasingly be captured and put to other uses, such as to warm adjacent greenhouses.Footnote 210 In the consumer domain, the AI Energy Star project, inspired by similar ratings for home appliances, aims to monitor AI carbon emissions and give the public information that will enable them to choose the least energy intensive AI model for a given task.Footnote 211 Despite these efforts, in a scenario with exponential growth of AI infrastructure it is unclear whether they would be sufficient to mitigate the environmental costs.

Implications

- Use of energy and water by the information technology sector could increase more than is currently being forecast

- Even if AI becomes more energy efficient, its total resource consumption could increase if this lowers costs and leads to AI being embedded in many more devices

- Economic pressure to expand data centres may compete with efforts to transition to green energy

- Public utilities could face increased challenges meeting the growing demand for clean energy. Considerations on the types of projects that are offered clean energy access may shift

- If AI companies increasingly turn to nuclear or other forms of energy to privately fuel the AI boom, this could create new pressures for organizations responsible for regulatory oversightFootnote 212

- Data centres could become increasingly controversial as they put pressure on land, water, and power supplies

- Inequities could emerge as those most impacted by the physical infrastructure of AI may not be the ones who most benefit

- Calls for stricter environmental regulation could grow if an increase in data centres causes more emissions and e-wasteFootnote 213

- Demand for strategic metals and minerals could grow, as data centres compete with green tech such as solar panels and electric batteries

- Platforms that automatically select AI models for a given task based on their performan and energy intensity could become common

- Tech companies may move towards deploying AI locally in their products to reduce use of data centres

- Use of energy and water by the information technology sector could increase more than is currently being forecast

Insight 12: AI could become more reliable and transparent

Alternative format

(PDF format, 4.4 KB, 5 pages)Date published: 2025

Cat.: PH4-222/2025E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-76905-9

In the future, AI could have improved reasoning skills, allowing it to produce better analyses, make fewer factual errors, and be more transparent. However, these improvements may not be enough to overcome problems related to bad data.

Today