Canada and the Changing Nature of Work

PDF: Canada and the Changing Nature of Work

On this page

Executive Summary

A New Context

Insights

Scenarios

Challenges and Opportunities

Conclusion

Annex A: Assumptions

References

Executive Summary

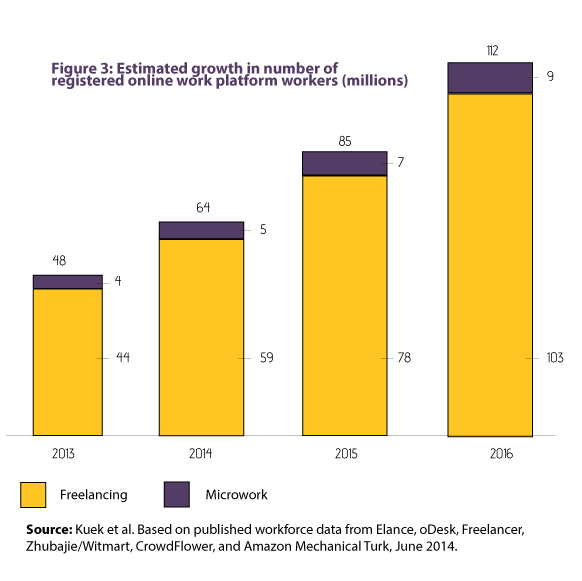

One of the more disruptive features of the emerging digital economy is the rise of virtual workers. Online work platforms (e.g. http://freelancer.com(link is external)) enable individual workers to advertise their skills and find short-term contracts with employers all over the world – creating a global digital marketplace for labour. An estimated 48 million workers were registered on online work platforms globally in 2013.1 The market is estimated to be growing at 33% annually, with the number of workers expected to reach 112 million and market revenue to hit US$ 4.8 billion in 2015.2 The advent of virtual work could profoundly reshape the nature of work in Canada, transforming how, when, where and what type of work is done. This in turn could challenge the underpinnings of Canadian social policy and programs such as employment insurance (EI) and the Canada Pension Plan (CPP).

Insights: What is changing?

- Work is Moving Online: Virtual work is growing at an exponential speed and is likely to be part of most Canadian’s work experience by 2030.

- Work is Becoming Borderless: Virtual work is available to everyone with an Internet connection and a smartphone or tablet to do both low and high skilled work on increasingly digital value chains.

- Work is Becoming Flexible but Uncertain: A global online marketplace will increase self-employment and short-term contracts, making job security and financial stability more difficult to attain.

Policy Challenges: As insights interact, what challenges could lie ahead?

- The rise of virtual work will facilitate skilled workers moving online and expose Canadians to global competition and opportunities.

- Virtual work could lead to a worldwide convergence of wages for similar tasks, potentially lowering Canadian wages over time. Transnational collaboration may be needed to avoid a global race to the bottom and to develop effective social policy instruments in the virtual international workspace.

- Virtual work will challenge implementation of existing legal and regulatory frameworks such as minimum wages, discrimination and tax collection.

- Access to social programs may need to be separated from employment status as full-time employment ceases to be the norm.

Virtual work may demand new and creative solutions on par with some of Canada’s most ambitious social policy initiatives from the past. It will likely take a transformational rather than incremental approach to keep pace with the changing nature of work and all that it entails for Canada’s social safety net.

A New Context

Policy Horizons Canada has explored in earlier studies, such as MetaScan 3, how influential digital technologies will be in shaping the world as we know it. The introduction of online web platforms along with other key technologies such as virtual telepresence, data analytics, robotics, artificial intelligence, sensors and 3D printing are unleashing a cascade of change that is transforming how, when, where and what type of work is done. Work has long shaped our lives, providing livelihoods, a sense of meaning and purpose, identity and social benefits to individuals and families. It has also anchored Canada’s system of social welfare, first as the impetus for labour standards, labour market access programs and employment insurance, and second, as a means of financing pensions and tax-funded social transfers. As a result, as work changes, there will be many implications for both individuals and Canadian society. This foresight study explores some of those more disruptive aspects, particularly of virtual work, and how they will impact social protection in the future.

‘Social protection is a collection of measures to improve or protect human capital, ranging from labor market interventions, publicly mandated unemployment or old-age insurance to targeted income support. Social protection interventions assist individuals, households, and communities to better manage the income risks that leave people vulnerable. ’

– World Bank cited in IDS Working Paper 232 “Transformative social protection,” by Stephen Devereux and Rachel Sabates-Wheeler, 2004.

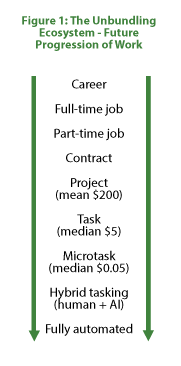

There are a number of forces converging that could accelerate the rise of virtual work in the next 10-15 years. Ongoing investments and advances in digital infrastructure are making quality Internet near ubiquitous, lowering the barriers to online participation around the world. An effort to reduce costs continues to drive the search for efficiencies in both the private and public sectors. “Unbundling” of work, in which complex projects are reduced to their constituent parts and contracted out to contingent workers online, is one way to cut costs and realize operational gains (Figure 1). More nimble employment models will be attractive to businesses who are dealing with ever-changing skills needs linked to rapid technological change. Self-employment rates are also rising. Although it is clearly linked to unemployment and may be the only option for some, self-employment is growing in attractiveness for a range of skill levels.3 Millennials’ emphasis on job fulfillment, freedom and work-life balance will likely mean that they pursue self-employment and a different type of career partly out of choice.4

Figure 1: The Unbundling Ecosystem – Future Progression of Work

This figure is entitled “The Unbundling Ecosystem: Future Progression of Work” shows a direction of change from more traditional work to unbundled work. The list moves from traditional to unbundled. Starting from the top and moving downwards we have: career; full-time job, part-time job; contract; project (mean $200); task (median $5); microtask (median $0.05); hybrid tasking (human + AI) and fully automated.

Insights

Insights describe developments taking place now that could create further, highly disruptive change in the future should they strengthen. Insights are selected for their disruptive potential and policy implications.

The rise of virtual work: from the office to the web

Crowd-based microwork and online freelance marketplaces

Online work platforms that offer a global marketplace for buying and selling labour are a rapidly growing part of the digital economy, connecting clients5 (usually businesses) with freelance workers around the world. The platforms allow businesses to “unbundle” complex projects into smaller units6 (Figure 1) that can be distributed globally through the Internet to an on-demand labour pool as needed, minimizing costs. They allow workers to reach a global market for their labour, presumably increasing their chances of finding flexible, paid work. There are over 145 such platforms,7 providing everything from generalists (e.g. UpWork, Freelancer) who do projects and tasks, to “clickworkers”8 who perform microtasks in the cloud (e.g. Amazon Mechanical Turk, Crowdflower) (Figure 2). An estimated 48 million workers were registered on these sites globally in 2013 with approximately 4.8 million active.9 Although this is small (estimated at less than 1% of the working population in both Canada10 and the U.S.11), the market is growing rapidly. It is expected to reach 112 million workers and US$ 4.8 billion in market revenue in 2015, growing 33% annually.12 By 2020, market revenue could be as high as US$ 46 billion.13 Freelancer expects 1 billion users in 10 years14while Upwork anticipates annual earnings of online freelancers to increase from US$ 1 billion to 10 billion within the next six years.15 Online marketplaces for physical services (such as Uber, Homejoy, TaskRabbit) and job placement are also growing (Figure 3). McKinsey estimates that by 2025, these types of platforms, all combined,16 could collectively raise global GDP to $2.7 trillion, increase employment by 72 million FTEs and benefit 540 million people.17

Online Freelancing

- Upwork (9 million freelancers)

- Freelancer (16 million freelancers)

- Hourly Nerd (Over 10,000 MBA graduates from top schools)

- Proz (766,603 translators)

- Fiverr (Over 3 million services)

Crowd-based Microwork

- Amazon Mechanical Turk (332,519 human intelligence tasks)

- Cloudflower (5 million contributors)

The development of crowd-based microwork and online freelancing platforms as a work model is at the early stages. If the growth trajectory of digital platforms in e-commerce (Amazon, eBay)18 and crowdfunding, which in 2015 is expected to account for more funding than venture capital,19 are any indicator, there is massive growth potential in this sector. Besides the drivers mentioned earlier, the proliferation of big data will likely create more need to gather, clean, mine and package data, fueling demand for microwork.20 Although current demand for microwork and online freelancing is driven by the private sector, there is also potential for it to grow in the public sector, with governments in the U.S. and Europe already experimenting with crowdsourcing.21 By 2030, it is possible that a great number —perhaps even the majority — of Canadians will secure at least some of their income through virtual work means.

Figure 3: Estimated growth in number of registered online work platform workers (millions)

This image illustrates a bar graph depicting the “Estimated growth in number of registered online work platform workers (millions).”

Online virtual worlds

Virtual worlds, such as Second Life, are another location of virtual work that could expand in the next 10-15 years. In these online worlds, users interact through avatars to generate activity, entertainment and economic exchange akin to real life. Some of the world’s largest companies (e.g. IBM, Accenture), recruiters (e.g. Randstad, Manpower), lawyers and other businesses (both real and virtual) have used Second Life for doing business.22 Second Life has also been the site of successful labour action and a U.S. government ruling on virtual workers.23 Although they first appeared as a new location of work in the mid-2000s, virtual worlds still offer a meeting place for real-time global collaboration. With augmented reality, advances in graphics and a growing telework trend, they may reemerge as a hub of global work and commerce.

Other types of virtual work include third party gaming services, in which someone is hired to play an online game to increase the power or status of a player, or to earn virtual currency or goods (that can be exchanged for real world currency), and “cherry blossoming,” paid online marketing such as Facebook “likes.”

All in the cloud

- Online Gaming Services (World of Warcraft)

- Sale of Goods and Services in Virtual Worlds (Second Life)

- Microwork (Amazon Mechanical Turk)

Obtained online

- Online Freelancing (Upwork, Freelancer): Completed on local device, delivered online

- On-demand Services (Uber, TaskRabbit): Completed and delivered offline

- Online Talent Management (LinkedIn): Traditional jobs located online

- Virtual Worlds as a Place of Work (Second Life): Traditional jobs convened online

A global rebalancing of wages

Between now and 2030, potentially billions of skilled and digitally connected workers from around the globe could move into virtual work. As Internet speeds continue to improve and virtual work spaces mature, inexpensive smartphones and wireless connectivity will afford even the disadvantaged an opportunity to participate in the global economy as virtual workers.24 Access to work anywhere on the globe will be made easier by high quality automated language translation provided by artificial intelligence (AI).25 Advances in telepresence will help open up whole new types of service work to be performed by virtual workers, and advances in telerobotics will move virtual work into physical tasks. Even in service tasks thought to require a local presence, robots with dexterous arms could be a game-changer in jobs as varied as surgery,26 mining27 and cleaning.28 Many countries could have a wage-rate advantage over the West, and with these advances, would bring global competition to a much larger range of occupations. This could drive a worldwide convergence in wages for similar work, lowering Canadian incomes over time and further exacerbating job scarcity caused by adoption of AI and robotics.

The World’s First Virtual Strike (for more detail, see Winifred Poster) In 2007, when Italian employees of multinational firm IBM were facing an unexpected pay cut, they organized a protest in the virtual world Second Life to voice their discontent. Their strike at IBM virtual headquarters included almost 2,000 avatar picketers from 30 countries. Their virtual action prompted the man responsible for the pay cuts to resign, and they won the real-life wage concessions they were seeking. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dja5rlSGo0s(link is external)(Video: 6 minutes)

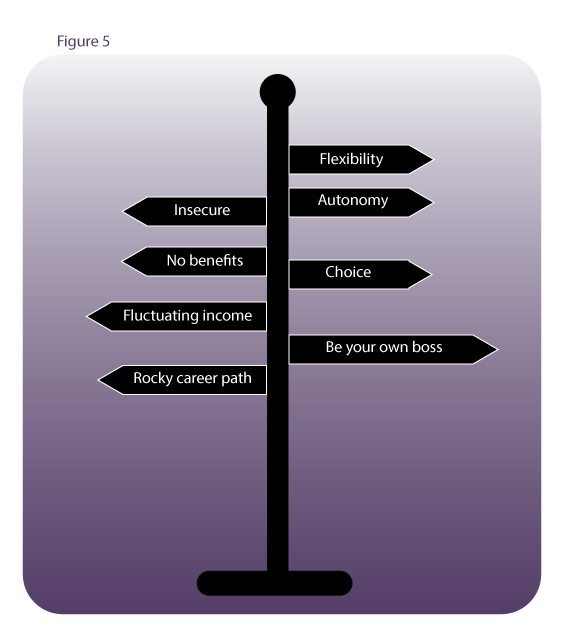

Uncertain job security

A growing online marketplace29 for work could make self-employment the dominant form of work in Canada, potentially leaving large numbers of Canadians with uncertain job security. Online freelancing opportunities could lower the barriers to entry for many would be entrepreneurs, allowing them to start their own small businesses with little capital. This would empower many with increased choice and flexibility (Figure 5). An online marketplace could also facilitate a more efficient matching of skills and reduce time spent unemployed.30 On the other hand, an online freelance model alters the traditional employer/employee relationship,31 turning workers – even those doing many small tasks for one client – into independent contractors. With unbundling of jobs, much of freelance work could be shorter duration assignments at lower pay rates.32 Unless other innovative sources of income security arise, as more and more jobs become virtual, workers may lack a predictable supply of work, regular and good wages, benefits like a pension plan, a path for advancement and access to today’s income security programs like employment insurance. The unbundling of work and its migration to virtual space could in these ways increase vulnerability among Canadians, contributing to the growing rise of the “precariat.”

Figure 5: Increased choice and flexibility

This image is entitled “Increased choice and flexibility” and highlights the positives and negatives associated with self-employment.

Exploitation in a virtual Wild West

Virtual work is relocating the job from a regulated environment to an unregulated one where current labour law does not necessarily apply.33 Platforms have widely differing standards, many of which create win-win situations for both clients and workers. However, this lack of regulation in the virtual work space has the potential to create an imbalance between clients and freelancers.34 On some platforms, clients have little obligation to the workers they contract: they do not provide benefits, do not always need to disclose context about the work requested and may not even be obligated to pay for work completed (Figure 6).35Recourse for workers who are treated unfairly in cyberspace is also limited at present. Outside the boundaries of the employer/employee relationship, labour law that sets standards around minimum wages, hours of work and working conditions no longer applies.36 The potential for exploitation is most stark in the microwork market where some platform workers have no way of negotiating with clients about the digital piecework they perform. Surveys of workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk indicate that for 18% of workers the compensation they receive is sometimes or always needed to make ends meet,37 yet the average pay is less than two dollars per hour.38 On any platform, with the click of the mouse clients can choose someone else and go where the labour is cheapest and the regulations are most lax.39 Although there are indications that some of these issues may be addressed in the future, for example through court cases40 or initiatives of the platforms themselves,41 online marketplaces could create pressure to reduce labour rights both online and offline. In an economic downturn, platforms would provide businesses with an opportunity to take advantage of workers. For these reasons, without new mechanisms in place, the emergence of virtual work on a global scale has the potential to erode past wage and labour rights gains.

Why you weren’t paid for virtual work

- You did the work to the specifications & your work wasn’t chosen – 99Designs

- The client rejected your work (but might still use it) – Amazon Mechanical Turk

- You can’t find work – you have a great reputation, but the workers in India are too competitive at a lower wage – Any platform

- Someone unfairly trashed your reputation and you can’t get it fixed – Any platform

Collective organizing among virtual workers: renegotiating fair exchange

The growth of virtual work is triggering a renegotiation of what constitutes fair exchange for labour. Even though the digital economy is changing many aspects of work, the aspirations of workers may not be shifting as much (Figure 7). Some platform workers have stated that they do not want regulation of their platforms, yet worker protests and campaigns for fairer treatment4243 indicate a desire for change. Gawker employees voted to unionize in June 2015, making it the first digital publication in the U.S. to do so, and a wave of others following (Salon, Vice, Guardian U.S. and Al Jazeera U.S.)44 illustrate that digital labour organizing may be feasible.45 A national drive to unionize digital media workers in the U.S.46 and a call for a transnational union of digital workers47 aim to demonstrate this further, despite the challenges of organizing a dispersed workforce with varied experiences of virtual work. Other forms of mutual support for workers are also emerging. These include software workarounds48 and forums49 to protect workers from unscrupulous clients, websites for worker campaigns,50 a growing number of worker-owned co-working spaces,51 and organizations like the Freelancers Union in the U.S., an association of freelance workers that advocates on members’ behalf and provides medical and dental insurance for members.5253 How this digital worker advocacy plays out will have significant implications for the well-being of Canadian workers and their degree of reliance on social programs. Renegotiation could echo early 20th Century labour movements and influence many aspects of virtual work in the digital economy.

Digital Workers would like the benefits of traditional employment

In a survey of Amazon Mechanical Turk workers that asked what could improve their experience, they listed:

- Minimum payment rate

- Dispute resolution mechanism

- A collective voice for workers

- More controls on not being paid, among other factors.

Source: http://wtf.tw/ref/felstiner.pdf(link is external) (p. 167/168)

In a survey of on-demand economy workers, top workplace desires were:

- Paid health insurance

- Retirement benefits

- Paid time off for holidays, vacation and sick days

- Workers were also interested in opportunities for advancement, education, disability insurance and HR support.

Source: http://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Workersurvey-reveals-challenges-o…

Work-life integration

The advent of virtual work is changing how, when and where work is done, collapsing the division between work and life and altering the career trajectories that have lent shape to Canadians’ lives. The relocation of work onto the web means it can be done from almost anywhere at any time. Greater numbers of people can now work from home or another location of their choosing, increasing access to work for groups whose opportunity may have been limited in the past (e.g. remote workers) and for those who need part-time work (e.g. stay at home parents).54 It will also facilitate working earlier (part-time gaming jobs for teenagers) and later (seniors who need a little extra income) and allow almost anyone to fill bits of time with income generating activity. From a productivity perspective, this is a great advantage. However, it also raises the issue of work intensification. Early studies have given a mixed review of the work-life mix of virtual work.55Workers have reported feeling isolated but also report higher satisfaction rates.56 New work/life configurations may require a different set of supports to meet the psycho-social needs of workers (e.g. the need for meaning, purpose, identity) and create a more fluid path through life stages (e.g. periodic sabbaticals instead of a long retirement). Virtual work will give many people an opportunity to reinvent themselves, but it is difficult to tell at this stage who will be the winners and losers in this new environment.

Scenarios

Scenarios are used to visualize how the future could evolve under different drivers and conditions. Scenarios are not attempts to predict the future, but rather to explore how the future might emerge, in order to test current assumptions and potential policy approaches against a range of alternatives.

Scenario 1: Patchwork of approaches (muddling through)

Ineffective attempts by government

As cost-conscious corporations embrace virtual work platforms, governments are challenged to keep-up with necessary changes to programs and regulation. A patchwork of regulations results from a hasty response, leading to ineffective national policy frameworks with few success stories. Dated eligibility guidelines and new realities leave many without a social safety net.

Society trudges along

Workarounds of various sorts become common practice among workers expected to be increasingly entrepreneurial. Higher levels of job insecurity and precarious work lead to lower overall incomes and growing inequality. Those with high-demand skillsets do very well, but the majority have mediocre opportunities as they can no longer rely on regular full-time work. Attempts at collective organizing are mostly too small to be globally effective.

Private sector adaptation

Managed platforms emerge in an attempt to replicate some aspects of traditional work culture to provide employees with a sense of purpose, challenge, development path and collegiality. Some firms develop their own in-house contracting platforms, although most draw from a global pool of contracting platforms. Most freelancers must constantly hunt contracts and learn to sub-contract, building their own network. Private sector options for benefits and social protection multiply for those who can afford it.

Scenario 2: Race to the bottom (incremental decline)

Missing the mark on global collaboration

Attempts at global cooperation to address the emerging issues related to virtual work have failed. The descent to the bottom has started as workers around the world compete to offer the lowest bid to win online work. Lower wages and difficulties in taxing virtual work bring about underfunded social programs in some countries.

Imposing corporations

A few companies own the majority of the virtual work platforms and have a high degree of influence on wages and labour standards causing widespread exploitation of workers. Attempts to institute a type of competition bureau remain more or less ineffective. Not everyone gets paid in currency. Some are paid in credits redeemable at virtual company stores.

One-way transparency

Big data and worker surveillance allow employers to monitor worker performance. Workers want more transparency in managing reputation systems that determine their work prospects. A clear hierarchy of platforms materializes. Status and prosperity is determined by which platforms workers can access, and this is linked to social markers (ethnicity, gender, citizenship). Attempts at breaking into blocked platforms with technology workarounds are difficult due to intense monitoring. Worker organization is low as participation threatens to jeopardize individual online marketability.

Scenario 3: Coordinated response (transformation)

Virtual workers unite

Widening income inequality becomes increasingly palpable. Governments inaction motivates large numbers of virtual workers to organize using social media. A next generation labour movement emerges that is successful in prodding a coordinated response between governments, private sector and workers.

A visionary global response

A coalition of forward-looking countries, virtual corporations, virtual work platforms and unions gradually agree on the essential elements in a new global policy framework to reduce worker exploitation, ensure fair wages and avoid a descent to the bottom. There is considerable effort to re-calibrate international labour norms and re-invent national social policy programs to coordinate at a global level. In some cases, contributions and calculation of benefits are managed and delivered digitally through new multi-party global platforms. International third party oversight networks monitor and enforce the new norms. For many workers with average skills in developed countries there is a descent to the middle rather than the bottom. Many governments and some platforms help workers learn new skills to move up the value chain. Successful national governments reinterpret regional, national and international dynamics to help their workers and firms adapt to new realities.

Responsible actors

Digital tracking tools allow workers, consumers and businesses to track the cause and effect of choices made along global digital supply chains. Corporate social responsibility becomes closely linked to profits, market penetration and sustainable business practices. Corporations and freelancers collaborate with governments to enforce new taxation models. While evasion and workarounds still exist, transparency reduces the benefits for those trying to game the system.

Challenges and Opportunities

Policy responses to the emerging world of work will need to act in the best interests of Canadians, establishing worker protections without crushing the innovative potential of virtual work. Although the current situation raises many concerns from a social protection perspective, it also presents an opportunity to reinvent work to better serve social policy goals. Responses could either: 1) stretch the existing system to better manage the emerging era of work or 2) transform it.57Responding optimally will require proactively identifying policy gaps and opportunities and reflecting on the role of government vis-à-vis the new work models.

Getting ahead of the courts: transforming the legal and regulatory framework

Many aspects of virtual work will challenge Canada’s existing legal and regulatory framework for employment, including labour legislation, employment standards, occupational health and safety and employment equity. Some issues are likely to make their way to courts, as in the U.S. There are 15 outstanding court cases there on the issue of whether virtual workers are employees or independent contractors.58 However, courts are limited by the existing legal and regulatory framework that they must apply and their decisions could inadvertently shutdown the emerging models in a way that is counterproductive. The emerging world of work may benefit more from a rethink of existing frameworks, and some new and creative solutions going forward. For example, many countries are discussing ambiguous employment relationships and a number have taken steps to make unemployment insurance easier to access for temporary workers.59 The EU is discussing a third category of worker, the “economically dependent worker” who is formally self-employed but depends on a single employer for their work and income. These discussions easily transfer to virtual work situations. Creating additional categories of workers would be a way to bring some of the most vulnerable virtual workers under the umbrella of social protections, as well to capture tax revenue from this stream. This type of novel solution would be more likely to serve Canadians than stretching an ill-fitting framework through a patchwork of court rulings.

Avoiding a race to the bottom: ensuring a fair and living wage

One of the biggest uncertainties about the emerging world of virtual work is to what degree it will provide a fair and living wage for workers. Some virtual work platforms are voluntarily instituting minimum payment levels.60 Self-regulation is inherently fickle, but does indicate potential leverage points for government intervention. However, there are also many difficulties to regulating minimum payment rates for online freelance work, and quite different alternatives to ensuring income security may need to be explored. A minimum income instead of a minimum wage is one such proposal that is gaining traction in many countries on both the political left and right.61 Although it would take some working out, including the funding mechanism, a minimum income could also help reduce the impact of technological unemployment on further exacerbating inequality.

Capitalizing on opportunities for labour market integration

McKinsey believes that online talent matching platforms will reduce the need for government labour market programs, as they will facilitate more efficient matching and reduce the length of time that people are unemployed.62 Virtual work also promises the possibility of improving access to work for the marginalized (those who are disabled or living in remote areas), helping people to re-enter the labour market and supporting people to develop their employability with new and varied skills. This is one of the reasons virtual work is being actively explored by organizations such as the World Bank and the Rockefeller Foundation as a development tool.63 However, there will also be a need to figure out how to support people in progressing through the virtual work system into more rewarding work. This will not simply be about upskilling as in the past. Rather, it may be about learning how to effectively market oneself and develop online workplace currency (reputation, brand).

Supporting the “jobrepreneur” and “micromultinational”: from accreditation to reputation

In a digital, automated economy, Canada’s workers will need to take an entrepreneurial approach to finding work, competing internationally as “jobrepreneurs” and “micromultinationals.” Small business start-up, management and promotion skills will be important, along with the ability to invent one’s own work to fill new market niches. At the same time, unbundling will deprofessionalize certain occupations and lower the level of skill required to do many jobs while the importance of online reputation grows. As a result, Canadians may need less accreditation and more reputation to strengthen their international position in the job market. A key skill will be managing one’s own personal presence on the web, including reputation and personal brand. Reputation will be established on an individual level, but in an international marketplace trading labour, there may also be an opportunity for Canada to establish a national reputation in certain market segments. International branding campaigns could boost individual Canadian’s competitive advantage in a global labour market.

Protecting personal reputations

As reputation becomes the main currency for securing work, a need for third-party regulation of reputation systems may evolve. As on Trip Advisor or many other online sites, negative ratings on a virtual work platform can be terminal.64 Currently, one of the ways most online work marketplaces keep users on their platforms is through their own private qualification and reputation scoring systems.65 However, workers are increasingly publicizing their reputation scores outside virtual work platforms (e.g. LinkedIn),66 suggesting the possibility of portable reputation scores in the future. Since detrimental scores could dramatically set workers back in the online work hierarchy, or even put them out of work, reputation will become a social policy issue. There may be a need for something like a reputation monitoring equivalent of a credit bureau, with some form of recourse for people for who feel they were wronged in a significant way.

Coordinating an international approach to social protection

An ongoing challenge will be enforcing social protections in an international virtual space. Walmart, a company that is routinely called out for exploitative practices in the U.S.,67 is a good corporate citizen on the Samasource platform, where it provides jobs for disadvantaged Kenyans.68 This underscores the difference that geography can make in defining good work or fair regulation. Country-specific policies will also be difficult to enforce using traditional instruments in a digital environment where many workarounds are possible. Despite the challenges, many measures could only be truly effective with international coordination. There is potential opportunity for transnational cooperation around issues such as fair wages and even social security. For example, platforms that have bettering workers as part of their mandate have voluntarily instituted minimum payment rates that are indexed to living wages in each country.69Wagemark,70 is another international voluntary initiative that allows companies to identify themselves as meeting certain labour standards. These types of initiatives could be encouraged or even made mandatory on a global basis in the future. Other measures that could be considered are global social insurance schemes regulated through domestic institutions,71 and supports for international collective organizing.

Updating social security programs

An obvious challenge of the new work reality will be the impacts of inadvertently decoupling income security measures such as employment insurance and pensions from employment. Canada’s social policies assume that employment is the norm, and unemployment the exception. But a global work marketplace and automated economy raises the potential future of fewer and more precarious jobs. This would limit the distributive function of employment (i.e. fewer people would have access to market income through jobs), as well as access to government or employer-sponsored benefits that are typically tied to jobs (e.g. sick leave, supplementary health and disability benefits, employment insurance, skills training, parental leave and pensions). This may require reconsideration of how Canada funds and delivers social security benefits. Developing a system of portable benefits that can follow workers from contract to contract and also protect the self-employed could be key. A U.S. group is actively advocating for this approach.72 Attaching social benefits to citizenship,73 or encouraging and underwriting citizen initiatives such as the insurance being provided by the Freelancers Union in the U.S. are possible options.

Distributing risk and responsibility between businesses, workers and the state

Canada’s social security system currently distributes risk between employers, employees and the state, who all shoulder some of the financial responsibility for social insurance measures. (Employers and workers in the form of employment-based contributions and taxes and the state through social transfers). In the emerging work configurations of the digital economy, businesses will realize significant cost savings from virtual work and robotics but offload their financial responsibilities for workers to the state and the workers themselves. Individuals will bear the brunt of ill health and workplace injuries (e.g. repetitive strain) with costs to society in the form of healthcare burden and productivity losses. The state will carry the burden of unemployment and underemployment. Even in an optimally working system, the proliferation of self-employed freelancers will transfer some costs to the social security system. Potentially lower overall incomes and higher rates of unemployment would be a further strain in the form of significantly reduced income taxes and higher social transfer needs. The challenge then, is how to redistribute this risk and rebalance the roles between businesses, workers and the state. One avenue would be new forms of taxation on businesses of a certain size, such as on their robotics systems, on the amount of Internet real estate they use (bandwidth) or on financial transactions. France, for example, is exploring new taxation options for other aspects of the digital economy.74 Consumer taxes, such as luxury taxes, “sin taxes,” and user fees in place of income taxes are another possibility.

Conclusion

As Canada navigates its way through the emerging digital economy and the new world of virtual work, there are many things to consider. A number of the changes explored in this study challenge existing assumptions about work and upset longstanding social policy assumptions (Annex A). A future of online, borderless work in which the majority of people are independent freelancers will no doubt bring unexpected challenges and opportunities. Some aspects will be positive. For example, the participation of Canadians (small and medium enterprises and individuals) in global digital value chains has the potential to open new business opportunities and unleash a new level of entrepreneurial dynamism in Canada. Other aspects will be more challenging. For instance, what happens when a job is no longer the best social policy, a ticket to stability and well-being? Change could be incremental but also rapid, surprising and disruptive, potentially increasing vulnerability for many. Canada now has an opportunity to anticipate and plan for these eventualities, ensuring that virtual work unfolds in a way that is in the best interests of Canadians.

Annex A: Assumptions

This foresight study challenges current assumptions about the expected future of work. It proposes alternative assumptions that are more likely to be robust across a range of future scenarios instead.

| Assumption | Robust Assumption |

|---|---|

| Most of Canada’s jobs will remain essentially the same in number and character. | Jobs will change dramatically in number and character, with fewer full-time jobs and more virtual workers in an increasingly global marketplace for labour. |

| Canada has a flexible and comprehensive social safety net, although it may be stretched in the future. | Changing forms of employment will challenge the flexibility and comprehensiveness of Canada’s social safety. It may need to evolve significantly to meet the needs of the future. |

| Canada has a strong labour protection system addressing issues like minimum wage and discrimination. | Canada’s current labour protection system may offer limited coverage in a world of international virtual work. |

| Unions are on the decline and belong to an era of industrial labour. | Collective organizing is relevant to virtual workers and the digital era, but will likely adapt and develop new forms. |

| Upskilling leads to better, higher paying jobs/education and training are the key to upward mobility. | A more varied mix of new skills and different kinds of credentials, along with a strong personal brand and self-marketing abilities, may be necessary to succeed in the emerging global virtual work marketplace. |

| A job is the best social policy. | In an employment-precarious world, jobs may not be enough to keep Canadians out of poverty and vulnerable circumstances. Canada may require new social policy models to distribute market income and social benefits that have typically been tied to jobs. |

References

1 Kuek, S. et al. 2015. “The global opportunity in online outsourcing(link is external).” World Bank Group. June 2015.

2 Ibid.

3 Frey, Carl Benedikt and Michael A. Osborne. 2013. “The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation?(link is external)” The Oxford Martin School. September 17, 2013.

4 Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas. 2014. “Why millennials want to work for themselves(link is external).” Fast Company. August 13, 2014.

5 In this study we have chosen to refer to those who pay for labour in the virtual economy as “clients” rather than “employers” in recognition of the breaking down of the employer/employee relationship. “Workers” is a more commonly used term that is easily substituted for “employee.”

6 The first stage of job unbundling is well established in the workplace (career and full-time work shifting to part-time or contracts).

7 Kuek, S. et al. This figure is from 2013, and as platforms are being created daily, it is likely an underestimate.

8 Also called microworkers, crowdworkers and cloudworkers.

9 Ibid.

10 Ipeirotis, P., personal communication, June 2015.

11 Kuek. S. et al.

12 Ibid.

13 Staffing Industry Analysts cited in Kuek, S et al.

14 “15 million lives changed(link is external).” Freelancer. p. 9. June 2015.

15 “Elance-oDesk relaunches as Upwork, debuts new freelance talent platform(link is external).” Upwork. May 5, 2015.

16 Manyika, J. et al. 2015. “Connecting talent with opportunity in the digital age(link is external).” McKinsey and Company. June 2015.

McKinsey’s estimates are for online freelancing platforms (e.g. Upwork), on-demand service platforms (e.g. Uber) and talent management platforms (e.g. Monster, LinkedIn, PayScale) all together.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Global crowdfunding market to reach $34.4 B in 2015, predicts massolution’s 2015CF industry report(link is external). Crowdsourcing.org.

20 Kuek, S. et al.

21 Ibid.

22 See Second Life web site(link is external), Second Life: Business(link is external), and Linden Lab’s infographic: 10 years of Second Life(link is external) for more information.

23 Cherry, M. Alabama Law Review. Working for virtually minimum wage. In June 2008 the U.S. IRS ruled that greeters for the Electronic Sheep Company in Second Life were employees, as opposed to independent contractors.

24 For example, see Samasource(link is external) and Cloudfactory(link is external).

25 Such as the free translation services already provided by Skype and Google. The quality of AI translation is already remarkable and will likely be near perfect by 2030.

26 Eveleth, Rose. 2014. “The surgeon who operates from 400km away(link is external).” BBC Future. May 16, 2014

27 Snyder, Jessie. 2015. “How the ‘rise of the machines’ will transform oil and gas(link is external).” Alberta Oil Magazine. March 16, 2015.

28 “Will remote-controlled robots clean you out of a job?(link is external)” New Scientist. December 3, 2014.

29 Unless otherwise specified, in the remainder of this study references to online and freelance marketplaces include both microwork and freelancing.

30 Mankyika, J. et al.

31 There is an ongoing debate about whether cloudbased microworkers should be considered as contractors or employees. They are currently treated as contractors in almost all cases.

32 Microtasks can be as short as seconds, the pay as low as pennies. One study found the average wage of Amazon Mechanical Turk workers to be US$ 1.25, at a time when the U.S. federal minimum wage was US$ 7.25/hour.

Felstiner, Alek. 2011. “Working the crowd: employment and labor law in the crowdsourcing industry(link is external).” Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law. p. 167.

33 Legal rulings are at the early stages. For example, in June 2008 the U.S. IRS ruled that greeters for the Electronic Sheep Company in Second Life were employees, as opposed to independent contractors. A June 2015 in California that determined Uber drivers are employees rather than contractors. Many other cases are before the courts in the U.S.

34 Silberman, M. 2014. “Designs for a future microtask market(link is external).” May 9, 2014.

35 For example, on Amazon Mechanical Turk, clients can refuse to pay workers without providing a justification, but still use and retain ownership of the work.

36 Howcroft, Debra and Birgitta Bergvall-Kareborn. 2014. “Internet provides new threat to employment rights(link is external).” Manchester Policy Blogs. December 9, 2014.

Existing labour law has for the most part not been applied. The participation agreement for Amazon Mechanical Turk workers explicitly states that “…workers are not entitled to holiday pay, sick leave, health insurance or compensation benefits in the event of injury. The terms and conditions offer no social protection for workers and there is no commitment to meet national minimum pay rates.”

37 Ross, J. 2010. “Who are the Turkers? Worker Demographics in Amazon Mechanical Turk(link is external).”

38 Ipeirotis and Ross cited in Felstiner, A. 2011. “Working the Crowd: Employment and Labor Law in the Crowdsourcing Industry(link is external).” Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law, Vol. 32, No. 1. August 16, 2011.

39 The following statement by Lucas Biewald, co-founder and CEO of one of the leading microwork platforms gives a sense of the disposability of workers in this work environment: “Before the Internet, it would be really difficult to find someone, sit them down for ten minutes and get them to work for you, and then fire them after those ten minutes. But with technology, you can actually find them, pay them the tiny amount of money, and then get rid of them when you don’t need them anymore.”

Biewald, Lucas (Co-founder and CEO of Crowdflower microwork platform) cited in Marvit, Moshe Z. February 5, 2014. “How Crowdworkers became the ghosts in the digital machine(link is external).” The Nation.

40 Legal rulings are at the early stages. For example, in June 2008 the U.S. IRS ruled that greeters for the Electronic Sheep Company in Second Life were employees, as opposed to independent contractors. A June 2015 in California that determined Uber drivers are employees rather than contractors. Many other cases are before the courts in the U.S.

41 For example, Upwork has strategies to keep their online marketplace from being flooded by low-cost labour (personal communication, September 2015).

42 For example, see the Amazon Mechanical Turk worker letter writing campaign to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos(link is external).

43 For example, see the No!Spec campaign against spec work(link is external).

44 Vasquez, Mario. 2015. “Wave of digital media organizing continues as Al Jazeera America goes union(link is external). In These Times. October 6, 2015.

45 Lehmann, Chris. 2015. “Digital-media workers of the world, unite!(link is external)” Aljazeera America. June 14, 2015.

46 Sterne, Peter. 2015. “Reporters announce conference in Louisville to unionize digital media(link is external).” Politico New York. June 8, 2015.

47 “Crowdsourcing grows up as online workers unite(link is external).” New Scientist. February 6, 2013.

48 For example, Turkopticon(link is external) is a software program that workers can use with Amazon Mechanical Turk to identify and avoid clients who take work without paying.

49 cloudmebaby.com(link is external) is a clickworker forum that shares tips and advice, for example, how to boost reputation ratings and make money more efficiently.

50 For example, see Coworker.org(link is external)

51 Cowork Niagara(link is external) in St. Catherines, Ontario “where freelancers, social entrepreneurs and non-profit groups work, collaborate and make awesome stuff together.”

52 See Freelancers Union web site(link is external).

53 Whitney, Heather. “Alternative Forms of Labor Organizations: Union Substitutes or Something Else?(link is external)” Digital Labor.

54 Ipeirotis, Panos. “The New Demographics of Mechanical Turk(link is external).” A Computer Scientist in a Business School blog. March 9, 2010.

Approximately 65% of Amazon Mechanical Turk workers are women, and it speculated that this is because more women have a need for part-time, flexible work that they can balance with caring for children.

55 Mandl, Irene. “New forms of employment: Status quo and first findings on crowd employment and ICT based, mobile work(link is external).” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. arch 28, 2014.

56 Mandl, Irene. “New forms of employment: Status quo and first findings on crowd employment and ICT based, mobile work(link is external).” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. March 28, 2014.

57 Johal, Sunil and Noah Zon. 2015. “Policymaking for the Sharing Economy: Beyond Whack-A-Mole(link is external).” Mowat Centre. February 16, 2015.

58 Cherry, M., personal communication. June 2015.

59 International Labour Organization. “World Employment and Social Outlook(link is external).” May 19, 2015.

60 “Crowdsourcing grows up as online workers unite(link is external).” New Scientist. February 6, 2013.

61 See:

• Coyne, Andrew. 2015. “Guarantee a minimum income, not a minimum wage(link is external).” National Post. June 10, 2015.

• Gordon, Noah. 2014. “The Conservative Case for Guaranteed Basic Income(link is external).” The Atlantic. August 6, 2014.

• Basic Income web site(link is external).

62 Manyika, J. et al

63 See for example the World Bank study on online outsourcing(link is external) referenced widely in this report and an earlier study, “Knowledge Map of the Virtual Economy(link is external).”

64 Stewart, James. “Online work exchanges and the ‘crowdsourcing’ labour(link is external).” Joint Research Centre – European Commission.

65 Ibid

66 Ibid

67 A list of anti-Walmart and pro-Walmart sites can be viewed on Reclaim Democracy web site(link is external).

68 Samasource. Customer Case Study: Walmart

69 For example, MobileWorks ties its minimum wages to each country where its workers(link is external).

70 See www.wagemark.org(link is external)

71 Murphy, Susan and Patrick Paul Walsh. 2014. “Social Protection Beyond the Bottom Billion(link is external).” The Economic and Social Review. Summer 2014.

72 “Common ground for independent workers(link is external).” Portable Benefits. November 9, 2015.

73 As in our healthcare system, or the Basic Income Guarantees being proposed internationally

74 Collin, Pierre and Nicolas Colin. “Task Force on Taxation of the Digital Economy(link is external).” Ministere de l’economie et des finance and Ministere du redressement productif. Government of France. Jaunary 2013.