Future Lives

On this page

- 1.0 Foreword

- 2.0 Executive Summary

- 3.0 Introduction

- 4.0 Life course

- 5.0 Forces of change

- 5.1 Figure 2: Forces of chance and life course components

- 5.2 Longer lifespans

- 5.3 Having fewer children, later

- 5.4 Social norms surrounding families

- 5.5 Data and AI-powered systems

- 5.6 Access to and accumulation of wealth

- 5.7 Rising anxiety about existential threats

- 5.8 Migration to and within Canada

- 5.9 How, where, and why of work

- 5.10 Social contract expectations

- 6.0 Possible implications

- 7.0 Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Endnotes

1.0 Foreword

For the last few decades, many people in Canada have gone to school, worked, bought homes, raised families, and retired near the age of 65. Governments have structured support around this typical life course. But the life course is changing.

New roles and life transitions are emerging. Exploring how these changes could transform future lives could improve life outcomes for many people in Canada.

Guided by its mandate, Policy Horizons Canada (Policy Horizons) is engaging with a broad spectrum of partners and stakeholders to look at how people in Canada could live life differently in the future. We intend to identify key areas of social change, and support policy and decision makers as they reflect on the shifting policy landscape.

On behalf of Policy Horizons, I would like to thank those who generously shared their time, knowledge, and thoughts with us.

We hope you find this work insightful.

Kristel Van der Elst

Director General

Policy Horizons Canada

2.0 Executive summary

An individual’s life course is made up of all the events and roles that they experience, and the sequence of these, over their entire lifetime. But in our rapidly changing world, the typical life course is changing, and this might have implications for policy frameworks. This report lays out an initial framework for thinking about transformative changes to future lives.

Six components of the life course take up much of our time, financial resources, and effort.

Transformations in these components will create new challenges and opportunities across different parts of society and the economy. Each component can be considered on its own, but they often overlap in time and affect each other. For that reason, they are best understood together.

- 1. Care

- We enter the world dependent on the care of those around us, and many of us will depart in a similar way

- 2. Reproduction

- Creating new life is a pivotal point of many people’s life courses. It is one of the primary ways that we link our lives with others

- 3. Education

- Education allows us to learn more about the world and find our place in it

- 4. Labour

- For most of us, labour is the primary way to pay for our lives

- 5. Living arrangements

- Everyone needs a place to live

- 6. Older adulthood

- Older adulthood is historically associated with working less, and both giving and receiving more care

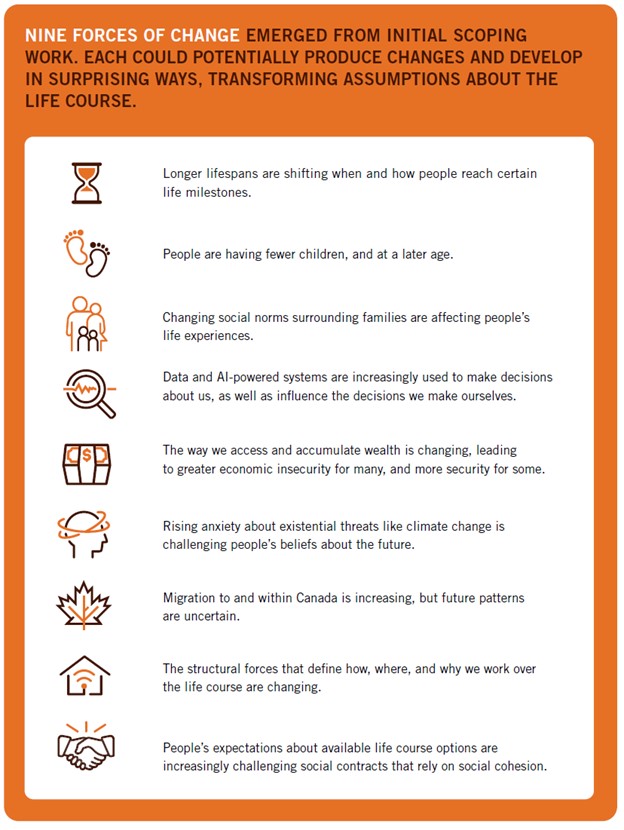

2.1 Figure 1: Nine forces of change

Figure 1 – Text version

Nine forces of change emerged from initial scoping work. Each could potentially produce changes and develop in surprising ways, transforming assumptions about the life course.

- Longer lifespans are shifting when and how people reach certain life milestones

- People are having fewer children, and at a later age

- Changing social norms surrounding families are affecting people’s life experiences

- Data and AI-powered systems are increasingly used to make decisions about us, as well as influence the decisions we make ourselves

- The way we access and accumulate wealth is changing, leading to greater economic insecurity for many, and more security for some

- Rising anxiety about existential threats like climate change is challenging people’s beliefs about the future

- Migration to and within Canada is increasing, but future patterns are uncertain

- The structural forces that define how, where, and why we work over the life course are changing

- People’s expectations about available life course options are increasingly challenging social contracts that rely on social cohesion

Possible implications

“These 9 forces of change may intersect with the 6 life course components to transform future lives. In the future, we could see the following changes.”

Care

- Global health crises could increase the care burden as people live longer with more chronic diseases

- People who become parents later in life might need different kinds of support

- When people have children later in life, future generations may be responsible for eldercare at a younger age

Education

- Frequent periods of unemployment for people in Canada could generate demand for rapid reskilling

- More transient lifestyles might create demand for more flexible education

- Radically new kinds of educational institutions may seek government recognition

Living arrangements

- More people in Canada could need to move due to climate events

- More people might migrate to Canada temporarily

- Demands may emerge to formalize new care and cohabitation relationships

Reproduction

- Tech companies and central data holders could have an outsized influence on who has children with whom

- More childless older adults might need care in old age and lack obvious heirs

- Research on the lasting impact of early childhood experiences may lead to new legal challenges

Labour

- The division could become starker between people who live off passively accumulated wealth and those who work full time for their income

- Care work might become better paid—and paid care more expensive

- “Kidfluencers” may call on digital content platforms to provide fair compensation, oversight, and work permits, and for a redesign of labour guidelines

Older adulthood

- Ageing adults could look for different ways to achieve economic security

- Pervasive ageism might decrease as older adults take up more space in society relative to other age groups

- Home design and infrastructure development may evolve to cater to an aging population

3.0 Introduction

Future lives explores how the life courses of people in Canada might change.

Over the years, society has broadly defined a certain kind of life course as “the norm”—you are born, attend school, start work, leave home, get married, retire, and so on. Since the post-war period, governments have largely structured programming and support for people according to the life roles and events associated with that perceived norm. However, a significant number of fundamental social, technological, economic, environmental, and/or political shifts are transforming our life courses. And out of choice or need, some people in Canada have rebalanced the time they devote to social relationships, leisure, employment, and education. Hence, this standard life course may not reflect the future life course for a growing number of people in Canada. It may also not reflect the present experiences of parts of the population in Canada, such as Indigenous peoples, migrants to Canada, or persons with a disability.

This report lays out an initial framework for thinking about transformative changes to future lives. It outlines some key components of the life course of many people in Canada. It explores the changes taking place in society that might transform those components and life courses overall. It begins to examine what these changes might mean for policy frameworks.

4.0 Life courses

What do we mean by life course?

An individual’s life course is made up of all the events and roles that they experience, and the sequence of these, over their entire lifetime. Our life courses are shaped by conditions and constraints that we cannot control, as well as by our own choices and decisions. They unfold in broader historical, economic, political, cultural, institutional, and collective contexts.Footnote1 Our decisions are influenced by our beliefs about the future, our internal states, and policies that encourage or discourage certain choices.

Reflecting on life courses, 6 components of life stand out. These components take a lot of people’s time, financial resources, and effort. They are: care, education, living arrangements, labour, reproduction, and a period of older adulthood. These components are shaped by data, culture, society, governance structures, and policy interventions. They often also involve one or more key decision points. Each component can be considered on its own. However, for 2 reasons, they are best understood together. First, they often overlap in time: we may combine roles as a worker, a carer for aging parents, and a parent to our own children. Second, they often affect each other: decisions about education, for example, shape our options for labour. Consequently, significant transformations within these 6 components may be relevant for future policies.

4.1 Care

We enter the world dependent on the care of those around us, and many of us will depart the world in a similar way. Care involves looking after others’ physical, psychological, emotional, and developmental needs. Care is required during periods of dependency throughout the life course. Those in need of care are generally infants, school-age children, people who are ill or have a disability, and older adults. In Canada, most care work is done, unpaid, by family members. Women in Canada spend about 2.5 more hours per day than men doing unpaid work,Footnote2 much of it relating to care. Government, non-profit, and for-profit institutions offer paid care services. Women make up 75% of workers in care professions, such as nursing, medicine, early childhood education, teaching, and personal support work.Footnote3 But women are paid less overall than men in the sector. A shortage of care workers is an emerging concern. There is also rising unmet demand for certain kinds of care, such as professional in-home care.

4.2 Education

Education allows us to learn more about the world and find our place in it. It equips us with knowledge and skills, and can shape our income, social class, identity, and social networks throughout our lives. Formal education has historically taken place in institutions such as schools, colleges, and universities. Today, new kinds of educational providers are emerging at all stages of the life course. Preschools, for example, that optimize learning through neuro- and cognitive science. Meanwhile, bootcamps offer fast training for in-demand tech roles. And free online courses designed by large corporations offer preferred employment to graduates. Education in Canada is largely funded by individuals and various levels of government.

4.3 Living arrangements

Everyone needs a place to live. Where and with whom one is able to live—that is, how safe, affordable, well located, and supportive one’s living arrangement is—shapes the life course profoundly. Where we live has historically determined our job options and how much we can earn. But increasingly, people are living where they can afford to live.Footnote4 Where people live also influences how much support they have from their family and community. Homes today are more expensive than ever to rent or own: 2 in 5 renter households in Canada spend 30% or more of income on rent and utilities.Footnote5 The cost of living in a place that is well located, safe, and supportive may constrain decisions in other areas of life, such as with whom one lives, or whether and when to start a family. Homes are increasingly expected to serve multiple functions. They might be a place for remote work or online learning, for example. They could also be a place to care for older family members.

4.4 Reproduction

Creating new life is a pivotal point of many people’s life courses. It is one of the primary ways that we link our lives with others. Ideas about the nature of “family” shape many other life course components. Decisions about whether, when, how, and with whom we have children are shaped by earlier participation in education and labour. These decisions may in turn shape our later access to options for labour and care. The life courses of each individual—their development, health, learning, and perceived place in the world—are profoundly shaped by gestational and childhood experiences, and relevant socioeconomic structures.

4.5 Labour

For most of us, labour is the primary way to pay for our lives. The support we received in childhood, and the educational paths we could access, often limit our work options. What we earn from labour determines how we can live and care for family members, and support our own needs when we grow old. For much of the twentieth century, it was the norm for one person in full-time employment to support a family. However, ideas about labour and valueFootnote6 are quickly changing. Shifts in working hours and expectations about job security are affecting many people’s life decisions.

4.6 Older adulthood

Older adulthood is historically associated with working less, and both giving and receiving more care. If we obtain them, the resources we store up early in life—from savings to housing status—heavily shape our experience of older adulthood. Many people today are continuing to work past the traditional retirement age of 65.Footnote7 Nearly a quarter of older adults care for ageing spouses, family members, or friends.Footnote8 Some become grandparents, a role that is increasingly recognized as central to child learning and development.Footnote9

5.0 Forces of change

This report identifies 9 forces of change that might shape people’s life choices by influencing what they know, what they believe about the future, or what they value in life. Forces of change are fundamental social, technological, economic, environmental, or political shifts that could transform assumptions about the life course. These 9 forces of change emerged from initial scoping work. They may affect the sequence and nature of the life course components described in the previous section, transforming assumptions in the decades to come.

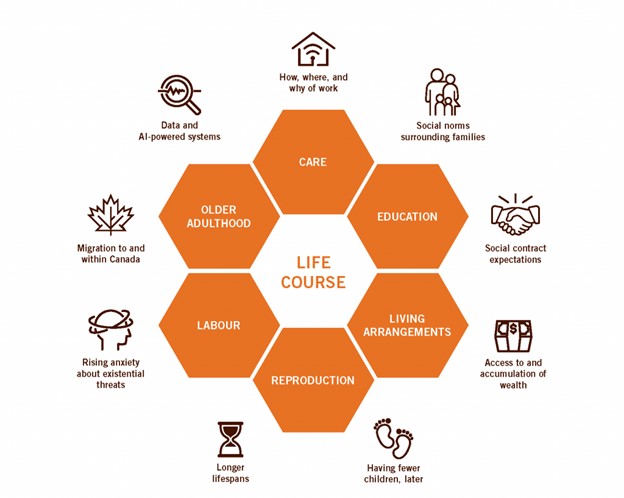

5.1 Figure 2: Forces of change and life course components

Figure 2 – Text version

Life course components

These 6 components of the life course take up much of our time, financial resources, and effort.

- Care

- Education

- Living arrangements

- Reproduction

- Labour

- Older adulthood

Forces of change

These 9 forces of change may affect the sequence and nature of the life course components.

- How, where, and why of work

- Social norms surrounding families

- Social contract expectations

- Access to and accumulation of wealth

- Having fewer children, later

- Longer lifespans

- Rising anxiety about existential threats

- Migration to and within Canada

- Data and AI-powered systems

5.2 Longer lifespans

Longer lifespans are shifting when and how people reach certain life milestones. Thanks to advances in science, medicine, and social policy, many people in Canada are living longer, healthier lives. This reflects global trends: by 2050, the number of people aged 60 and over will double to more than 2 billion.Footnote10 But social and economic inequalities continue to shorten lifespans for many in Canada, such as for Indigenous peoples.

Longer lifespans are changing the timing and nature of life course events. Younger generations are starting careers, getting married, buying homes, and having children later than older generations. We may be witnessing the emergence of “extended adolescence.”Footnote11 Behaviours historically associated with teenagers (ages 14 to 19) are extended in both directions (down to 10 and up to 24).Footnote12 The biological changes of puberty are, on average, beginning earlier. Meanwhile, the semi-dependency that characterizes adolescence is lengthening into early adulthood. This reflects factors such as the rising cost of living, more precarious employment, technological change, and shifting social expectations.

Gerontolescence is a stage that emerges with longer life expectancy. It reorients the approximate period of age 50 to 75 toward self-discovery and the pursuit of new careers or hobbies.

Many people can live healthier lives for longer. Some people are prioritizing health and wellness to maintain vitality and physical, mental, and emotional function later in life. But common chronic illnesses affect 73% of adults aged 65 or older.Footnote13 And a growing number of peopleFootnote14 have 2 or more such diseases.Footnote15 COVID-19 could add to the burden of chronic disease, and also shorten expectancy of a healthy life.Footnote16 Advances in biodigital technologiesFootnote17 are promising to restore or enhance certain physical and cognitive abilities. But some people may be effectively excluded from access. Meanwhile, technologies such as gene editing may raise ethical issues through their impacts on unborn generations.

As people live longer, they continue to work longer as well. More than a quarter of people aged 65–69 in Canada are still employed.Footnote18 Some work because they lack savings or support, but most say it is a personal preference.Footnote19 For many, a new phase of self-discovery is emerging around the ages of 50–75. It is sometimes called “gerontolescence”Footnote20—a kind of adolescence for older adults. Others never reach this phase, due to disadvantages earlier in life that affect quality of life and life expectancy in profound ways.

Increases in longevity are far from equal across Canada. Life expectancy is affected by persistent inequalities in poverty, educational attainment, unemployment, and access to non-discriminatory healthcare. A Vancouver study shows a 30-year gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest neighbourhoods.Footnote21 A 1-year-old First Nations, Métis, or Inuit child can expect to live 9-10 fewer years than a non-Indigenous child.Footnote22 At the same time, Indigenous adults are twice as likely to die from an avoidable cause.Footnote23

5.3 Having fewer children, later

People are having fewer children, and at a later age. New reproductive technologies are making it more feasible for some individuals to delay giving birth until later in life. The choice to be childless is also increasingly destigmatized.

Some people in Canada are choosing to delay or forego having children, for reasons including economic instability, anxiety about the future, or lack of affordable childcare. According to Statistics Canada,Footnote24 19% of those aged 15–49 said they want fewer children or to have a baby later than planned because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Only 4% said the pandemic had made them want more children or to have a baby sooner. One in 5 young people in Canada said they would like to have children but feel they cannot afford to.Footnote25 One in 4 childless adultsFootnote26 says concern about climate changeFootnote27 was a factor in the decision not to have children.

Trade-offs between fertility and economic security remain challenging, particularly for women. Fertility rates are dropping among younger women, and rising among older women.Footnote28 This is partly because more women are in education and in the workforce. Women continue to earn a lot less than men.Footnote29 This is largely due to a “child penalty”Footnote30 that women pay when they leave the workforce for long periods to care for children.Footnote31 Women making this decision became increasingly common during the pandemic.Footnote32 Women are twice as likely as men to work part time.Footnote33 They also make up a larger share of less regulated professions, such as gig workersFootnote34 and social media content creators. Less stable employment affects maternity leave supports. It also has an impact on when women return to the workforce, how much they earn over their lifetime, and how much they can save for retirement. The persistent gender pay gapFootnote35 leads to a gender pension gap later in life.

Individuals who want children later in life have more options than ever. They are increasingly turning to surrogacy, egg or sperm donation, or frozen embryos from other peoples’ IVF treatments.Footnote36 Such solutions are costly and not accessible to everyone. This may further intensify trends toward people having fewer children and smaller households. In turn, this might increase pressures for governments and the private sectorFootnote37 to pay for these efforts.

5.4 Social norms surrounding families

Changing social norms surrounding families are affecting people’s life experiences. The proportion of families with 2 parents and children living under the same roof is getting smaller. Meanwhile, the number of single-parent households has grown. Society is challenging norms such as having one primary partner. More young people are living longer with their families or roommates before forming their own households. Some are never leaving home.

Cultural and political definitions of “family” are increasingly dissociated from genetics or biology. People whose children are born from egg or sperm donation are forming new types of family centred on “diblings,”Footnote38 or donor siblings. New kinds of relationships, such as those formed by choice and with intention, are blurring traditional distinctions between “friends” and “family.”Footnote39

Social norms surrounding sexual orientation, gender, and relationshipsFootnote40 are rapidly evolving. Young people are having less sex than older generations.Footnote41 They also engage in more ethical non-monogamy.Footnote42 They stick less to “male” and “female” identities, and self-identify according to a much more diverse and fluid set of sexual orientations. The declining proportion of married couples over the last half centuryFootnote43 suggests that marriage may be increasingly irrelevant to younger generations.Footnote44 Marriage may fall out of favour altogether, but it may also evolve. Future changes could reflect the evolution of gender-fluid language, culture, and norms that challenge the dominance of opposite-sex marriage.

The makeup of households and work-from-home arrangements are affecting trends in caregiving and support from families. The 2018 General Social Survey shows that a quarter of people in Canada had cared for someone with long-term needs during the previous year.Footnote45 This care commitment often required adjustments to living or work arrangements. Women accounted for two-thirds of caregivers that provide more than 20 hours of care per week. The COVID-19 pandemic may have made these gendered patterns even worse: women in Canada did a larger share of parental tasks,Footnote46 especially when they worked from home. Meanwhile, multigenerational households were the fastest-growing type of household in Canada from 2001 to 2016. During that period, the number of such households rose 37.5%. They were especially common in immigrant and Indigenous populations.Footnote47 In both CanadaFootnote48 and the U.S.,Footnote49 COVID-19 may have caused millions of young people to move home to live with their parents. Indeed, there was an early-pandemic bump in young adults returning home.Footnote50 April 2020 marked the first time that the majority of American 18–29 year-olds were living with their parents since the Great Depression.Footnote51 Beyond the early impact of COVID-19, there is a sustained long-term trend of young people living at home with their parents until later in life.Footnote52 Young people may also opt for alternative living arrangements, by choice or by necessity. Intentional communities,Footnote53 for example, pool resources and live collectively.

More and more, we expect our health and wellness needs to be met in our homes. However, in 2015/2016, an estimated 433,000 people in Canada had home care needs that were not fully met.Footnote54 In an era of growing individual freedoms, single-occupant homes are now the most common type of home in Canada; they have more than doubled to 4 million since 1981.Footnote55 As demographics and the makeup of families change, healthcare services are expanding to fill certain care gaps. These include postpartum hotelsFootnote56 for new parents who lack family support, and dyadic healthcare,Footnote57 where new parents and children are treated together. More providers are also offering home screening and diagnostic services.Footnote58 In certain places, postal workers offer visits and prescription drop-offs to isolated older adults.Footnote59

5.5 Data and AI-powered systems

Data and AI-powered systems are increasingly used to make decisions about us, as well as influence the decisions we make ourselves. Deep learning algorithms use data gathered from a variety of sensors and devices to find patterns. Using these patterns, they can make educated guesses about us, and predict our behaviour. Such algorithms have become increasingly pervasive. They shape the life course by conditioning what we believe, the choices we make, the choices others make about us, and our engagement with others and the world.

AI-powered systems are reshaping routine life experiences in a bid for greater efficiency. Policing and airport security are rolling out technologies that can recognize facial features. Car insurers use telematics devices to determine rates based on how we drive. Financial service providers use AI for trading decisionsFootnote60 and to evaluate creditworthiness.Footnote61 Retail beacon technologies link online and real-life shopping behaviour with apps that nudge users into nearby shops.Footnote62 Once in the stores, technologies that track eye movement collect data that inform in-store suggestions for the shopper. Technologies that tailor learning plans to student needs claim to improve learning efficiency 5 to tenfold.Footnote63 Deep learning algorithms are being applied to make health screening and diagnoses more personalizedFootnote64 and accurate.Footnote65 All this focus on efficiency may often conflict with other values such as freedom, fairness, transparency, or privacy.

Online, algorithms are used to capture people’s attention and shape the information they are exposed to. This affects who they interact with and what they believe about the world. People increasingly expect experiences that seamlessly anticipate and meet their personal needs.Footnote66 This may also alter our expectations of government services.

Sometimes algorithms can constrain human agency, and sometimes they enable it. In either case, they introduce greater speed, complexity, and opacity into human decision making. Personal data is becoming more widely available. As a result, AI may play an ever-larger role in guiding people in many life decisions. We may not fully appreciate yet how data capture and use are reshaping how we understand ourselves and how we act in the world.

5.6 Access to and accumulation of wealth

The way we access and accumulate wealth is changing, leading to greater economic insecurity for many, and more security for some. How people accumulate and spend wealth affects life courses across generations. Historically, wages and savings were the most common way for most people to build wealth, but this is beginning to change. Unequal distribution of wealth continues to constrain people’s life choices, despite the overall household wealth of people in Canada increasing steadily over the past several decades.

Wages and savings become less valuable. The cost of housing and other real goods is rising in a context of greater job market and economic volatility. As it does, wages and savings are becoming much less relevant to future economic security. This is especially true for those at or below the median income. Those who rely only on wages and savings could become more reliant on new forms of debt to maintain households and bring about key life course transitions.

Economic insecurity and volatility make long-term planning more difficult. Individuals cannot be certain their jobs will exist in 10 to 15 years. Investments are more volatile, with uncertain medium-term returns. Economies have become more reactive and prone to short-term fluctuations due to geopolitical and institutional instability. Inflation has reached the highest level in recent decades, which makes it more difficult to afford things. The household debt-to-income ratio has reached record levels: $1.86 in household debt accompanies every dollar earned by a household in Canada.Footnote67 Combined, these factors may contribute to greater instability in people’s financial situations.

The gap between the wealthiest and least wealthy households in Canada remains large, despite a recent decrease. By the end of 2021, the top 20% of households held more than two-thirds (67.13%) of all net worth in Canada; the bottom 40% accounted for only 2.83%.Footnote68 Poverty especially affects people living alone, including 33% of working-age singles.Footnote69 The average annual household income for low-income, single parents with one child is now 44.1% below the low-income measure after-tax poverty line.Footnote70

Inheritances are becoming more important because both wealth and poverty can be passed down. As wealth inequalities continue to rise, inheritances and capital gains are becoming more central to shaping future economic outcomes for more people.Footnote71 An estimated $1.2 trillion in intergenerational wealth transfers will take place over the next decade.Footnote72 The people who will most likely receive the most benefit will be those who belong to affluent households and who were born between 1955 and 1980. At the same time, it is becoming harder to escape poverty. Children born in the poorest families between 1982–1985 are more likely than ever to stay poor, compared to children born in the poorest families between 1963–1966.Footnote73

5.7 Rising anxiety about existential threats

Rising anxiety about existential threats like climate change is challenging people’s beliefs about the future. As extreme weather events become more frequent, people are becoming more concerned about ecological risks. Rising existential anxiety is affecting people’s health, socioeconomic security, attitudes, cultural practices, and decisions about where and how to live.Footnote74

Mental health issues are increasingly being destigmatized and receiving more attention in the workplace, schools, and peer groups. The COVID-19 pandemic has added to high levels of mental health distress in Canada. This has increased demand for mental health services. Pollution and climate change are recognized as affecting mental as well as physical health.Footnote75 Ecological grief and eco-anxiety are emerging conditions that may not be easily treated by existing approaches.Footnote76

People’s beliefs about the future are affecting how they behave in the present. Some groups are getting more anxious and angry about what they see as lack of action on climate change. This is especially the case for youthFootnote77 and communities with strong relationships to the land.Footnote78 These emotions manifest in political engagement, activism, distrust of institutions, and lawsuitsFootnote79 against governments to try to force more action. Demands are growing for new forms of legislation that require decision makers to consider future generational impact.Footnote80 Some people are modifying their personal consumption habits to help fight climate change. This can include using lower-emission transportation, or eating less red meat and dairy.

Many young families are giving up the dream of home ownership due to climate uncertainty, on top of economic reasons. Historically, buying a home has been widely viewed as a central objective in life. This is partly because it allows people to build wealth passively. However, climate change is narrowing options. More extreme weather is making it difficult to insure properties in the growing number of areas at high risk of flood, wildfire, or permafrost thaw.

Climate change is threatening food security, infrastructure, and traditional ways of life for Indigenous communities. Climate change could disrupt agricultural production globally, as well as raise the possibility of new pests and drought. This, in turn, could affect the availability and cost of food. Wildfires and floods have forced tens of thousands of British Columbians to move over the last 5 years.Footnote81 Many others in high-risk zones may choose to move in coming years. Climate change continues to disrupt food security and our ways of life. For example, climate change upsets the seasonal rhythms of the land.Footnote82 This affects activities like planting and harvesting traditional medicinal plants, hunting, and ice fishing. Transportation infrastructure is also put at risk. Flooding and landslides in British Columbia, for example, have damaged bridges, highways, and large sections of road. In Northern communities, ice roads are safe for fewer days per year. This makes it harder to get essential supplies to remote territories. As a result, communities can no longer count on holding traditional annual events that are relied upon for health, safety, work, and leisure.

5.8 Migration to and within Canada

Immigration to and within Canada is increasing but future patterns are uncertain. Canada’s immigration planFootnote83 emphasizes the social and economic benefits of immigration. In 2021, Canada welcomed the most ever immigrants in a single year. Internal migration is also accelerating. In the second quarter of 2021, more than 120,000 people moved to another province or territory, the most in 30 years.Footnote84

Canada plans to welcome almost half a million immigrants per year between 2022–2024. Demands to allow migration to Canada are likely to get stronger as climate eventsFootnote85 and global conflicts continue to displace people across the world. However, there is uncertainty about future migration patterns. Key uncertainties include, among others: the longer-term impact of COVID-19 on borders and mobility,Footnote86 increasing competition for skilled immigrants between countries with aging populations,Footnote87 and the extent to which migrants to Canada will remain in Canada over the longer term. For instance, 30% of young, recent, university-educated new Canadians reported being likely to move to another country in the next 2 years.Footnote88 Many cited the rising cost of living in Canada as a factor of concern.

Technology allows more people to maintain their social and professional lives from anywhere in the world. There is less need for people to live where they work.Footnote89 Some people in Canada see a nomadic lifestyle as viable: for example, living year-round in a van, truck, or RV, with no fixed address. Still others travel across Europe, Asia, and Africa while working remotely, as digital nomads.Footnote90 Some countries have introduced nomad residence permitsFootnote91 for remote workers who wish to migrate but remain employed in their country of origin or another country.

5.9 How, where, and why of work

The structural forces that define how, where, and why we work over the life course are changing. More people in a position to do so want work to fit how they live, rather than to build a life around their work. The standard 5-day, 40-hour workweek of the twentieth century is increasingly being challenged. Remote work has become an option for more people. But contract and gig work have also made income more unpredictable. At the same time, automation makes certain career trajectories less stable. Attitudes toward the role of work throughout the life course are shifting. Whether these shifts will continue post-pandemic is uncertain.

People increasingly earn money in ways that do not fit neatly with current structures to regulate labour and income. These include social media influencing and informally turning hobbies into money-making ventures,Footnote92 among others. Working multiple jobs is becoming more common. This can be due to financial insecurity, or because it is a feature of the gig economy. It may also happen because remote work has made it easier to do 2 full-time jobs from home at once without anyone noticing.Footnote93 Employment tends to be mostly associated with public or private employers. Rates of self-employment have decreased steadily over the pandemic.Footnote94 This suggests a structural change in the feasibility or desirability of working for yourself.

Career changes have become more frequent. The pandemic led many workers who were juggling priorities to re-evaluate their jobs, and the time and space work was taking in their lives. Some left paid work to care for family. Others are demanding better pay and conditions, disillusioned with how power dynamics and the tax system seem to favour the wealthy.Footnote95 However, labour shortagesFootnote96 that give employees more bargaining power may not hold. In the future, changes in market conditions could constrain people’s options for more flexible work conditions.

The need to reskill has become normalized as more people want or need to switch careers. Knowledge from schools is becoming outdated more quickly in the workplace. Flexible and continuous reskilling throughout the life course makes it easier to switch between different industries and job types. Online learning is making it possible to learn new skills more flexibly and cheaply. Online options include an informal marketplace of coaches, massive open online courses (MOOCs), bootcamps, corporate-designed education,Footnote97 and career accelerators.

5.10 Social contract expectations

People’s expectations about available life course options are increasingly challenging social contracts that rely on social cohesion. People in Canada have different beliefs about whether and how the social contract should change. More and more, individuals are expressing socioeconomic grievances, challenging the relationship between governments and people. For some, individual aspirations are much more influential than collective goals and identities in shaping allegiances, behaviours, and sense of self.

Norm-defining community institutions like schools, workplaces, and religious organizations are less influential than they once were. More people are basing life decisions about procreation, healthcare, and education on information from alternative authoritiesFootnote98 and decentralized communities than in the past. Such communities have marshalled significant resources through informal channels, such as cryptocurrency exchangesFootnote99 and crowdfunding platforms.Footnote100 This could give them more power to forward their agendas in new and less visible ways.

Communities that perceive themselves as excluded are challenging the view of Canada as a unique “mosaic” that accepts all types of differences. They highlight the effects of systemic “-isms,” and demand more substantive representation and equity. Others craft nostalgic narratives around the values of the “good old days,” widening social divides. Some who feel ignored and left behind economically are increasingly open to political radicalizationFootnote101 due to their distrust in government institutions.Footnote102

Individuals increasingly aspireFootnote103 to lifestyles that they find difficult to attain. The rise of online content creators and influencers is widening gaps between what people think they ought to be able to achieve and what is feasible in today’s socioeconomic and political climate. This is making people unhappier with existing institutional support and even leading to a rise in “deaths of despair.”Footnote104

6.0 Possible implications

What could we see in the decades to come? The 9 forces of change may intersect with the 6 life course components. If this happens, it may create new challenges and opportunities across different parts of society. This could transform future lives in unexpected ways.

6.1 Care

Global health crises could increase the care burden because people are living longer with more chronic diseases. If people live both longer and healthier lives, they may need less care as they age. But global crises may lead to more need for care. For example, the long-term health impacts of COVID-19, climate change, and increasing rates of poverty and mental illness remain unknown. With rising needs for care, more people may drop out of education and paid employment to look after others. In addition, rising needs for care may lead to new demands for support.

People who become parents later in life might need different kinds of support. As people start families later, they may not have their children’s aging grandparents to help with childcare. Indeed, members of the growing “sandwich generation”Footnote105 struggle to meet the demands of caring for both children and seniors at the same time. Given the trend toward smaller families, parents may also have fewer siblings. That means parents may not have as much help right after the baby is born or to raise the child over the longer term.

When people have children later in life, future generations may be responsible for eldercare at a younger age. With delayed parenthood and shrinking family support networks, more young people could be pushed into caregiving roles earlier in life. This could affect their ability to complete postsecondary education or training, earn an income, or start a family. Care systems in Canada assume that caregivers are adults who can access support from employers or governments.Footnote106 Institutional structures that would keep families with complex, intergenerational care needs together under one roof do not exist.

6.2 Education

Frequent periods of unemployment for people in Canada could generate demand for rapid reskilling. As knowledge becomes more quickly obsolete in the labour market, it could lead to demands for rapid reskilling. This applies both to people who are employed and to those who lose their jobs because their skills are no longer relevant. Formal educational qualifications may become less important to get hired. It may become normal for people to learn new skills throughout the life course. As a result, people may find new ways of proving their skills to potential employers.

More transient lifestyles might create demand for flexibility in education. As online learning means students can live anywhere, tuition fees could be linked to where people live rather than at which institution they study. Given rules around residency, young children of transient parents may find it hard to access education and certain kinds of benefits as they move from place to place. As parents’ working hours generally become more flexible and less predictable, the “normal” school day may also need to be rethought.

Radically new kinds of educational institutions may seek government recognition. As demand rises for learning across the life course, new kinds of educational institutions could emerge. Some may focus on skills training for jobs. Others may seek to promote alternative ideologies, such as those held by the varied groups of the Alt-Right.Footnote107 Such institutions could arise initially through private funding campaigns. Eventually, they might seek formal government recognition or funding.

6.3 Living arrangements

More people in Canada could need to move due to climate events. Natural disasters such as floods, heatwaves, and wildfires used to happen “once in a century.” As such disasters become more frequent, more people may need help relocating their families, possessions, and livelihoods. They may also need help adapting their most valuable asset—their homes—to the changing climate. In some cases, efforts to mitigate or adapt to climate change might force people to leave their homes. Meanwhile, more climate migrants might seek to settle in Canada as it becomes impossible to liveFootnote108 in their home countries.

More people might migrate to Canada temporarily. The assumption that people who migrate to Canada will stay here may not hold. Immigrants typically settle in large urban centres. As a result, they may be more affected by rising costs of living. They may also have a greater need to share housing with their extended family. Immigrants to Canada may consider returning to their home countries or migrating elsewhere if socioeconomic conditions change or new incentives emerge. New questions around social benefits and protection may arise if temporary migration becomes more common.

Demands may emerge to formalize new care and cohabitation relationships. As new family configurations and relationships of care become increasingly normalized, we could see demands for these relationships to receive a formal legal status. There could be demand for different childcare or custodial relationships to have a formal legal status analogous to marriage. These relationships might involve, for example, non-sexual partners or more than 2 primary parents.Footnote109 This might involve requests for legal benefits and obligations in areas such as care and cohabitation, as well as transfer of wealth and assets.

6.4 Reproduction

Tech companies and central data holders could have an outsized influence on who has children with whom. More people may continue to find romantic partners via dating apps. If so, algorithms will be bringing together more new parents in the future. Dating apps based on genetic matchingFootnote110 could be marketed as a way to prevent hereditary disease, may reinforce prejudice against certain groups and lead to ethical concerns over new forms of eugenics.

More childless older adults might need care in old age and lack obvious heirs. Currently, younger family members do much of the eldercare. As a result, childless older adults may demand alternative arrangements to provide the care they need. They may also look to informal social arrangements, such as seeking care from friends or more formalized cooperative living arrangements. Childless older adults may find new ways to distribute any wealth and property they have accumulated.

Research on the lasting impact of early childhood experiences may lead to new legal challenges. Governments and corporations have increasingly faced legal challenges based on future generations’ right to climate justice and a sustainable tomorrow.Footnote111 Future legal challenges might be rooted in research into epigenetics—especially the effects of government-funded interventions on child brain development.Footnote112 People may trace their physical and mental health disadvantages to experiences such as poverty, malnutrition, exposure to chemicals, or trauma in the gestational or early childhood periods. In response, they may demand redress from parents, governments, and corporations.

EpigeneticsFootnote113 is the study of how environmental and behavioural factors can turn certain genes “on” or “off.” Some epigenetic changes are reversible, while others are permanent. Epigenetic changes continue through life. However, research suggests that the gestational period and early childhood years are uniquely sensitive. During pregnancy, for example, stress, trauma, and poverty, as mediated through factors like nutrition, can alter an unborn baby’s gene expression. This can increase the chances of heart disease, schizophrenia, and diabetes later in life.

6.5 Labour

The division could become starker between people who live off inherited wealth and those who work full time for their income. The “great intergenerational wealth transfer”Footnote114 could deepen the divide between social classes. On the one hand, there are people who must work to live. On the other, there are those who can live off capital assets such as property and stocks. People who do not inherit assets may find them increasingly hard to accumulate. This could lead to more social discord and counter-cultural practices. For example, in the movement known as “lying flat,”Footnote115 Chinese youth simply opt out of work. People without personal wealth may look more to governments for support. Meanwhile, the wealthy may seek even more sophisticated ways of hiding their assets.

To lie flat means to forego many of life’s typical milestones, such as getting married, having children, and buying a house. It can also include not being employed.

Care work might become better paid—and paid care more expensive. More older adults may lack family members nearby to care for them and rely more on paid care workers. This may lead to shortages of care workers. These shortages may then lead to higher wages to help attract people to these jobs and give them a reason to stay. Countries may increasingly compete for skilled care workers. Rising care costs could increase pressure on family members to exit the paid workforce to care for relatives.

“Kidfluencers” may call on digital content platforms to provide fair compensation, oversight, and work permits, and for a redesign of labour guidelines. The line between productive economic activity and leisure has been blurring as online platforms profit from the engagement of their users by aggregating and monetizing data. In some cases, such as “kidfluencers”, video content of children doing activities such as opening or playing with toys is monetized through ad revenue. As kidfluencers grow up, they may collectively begin to raise questions about consent, fair compensation, oversight, work permits, labour guidelines, and taxation.

“Kidfluencers” are children with large social media followings, who often earn money for sponsored content—an estimated $8 billion in 2020.Footnote116 Their parents typically manage their activities. Some jurisdictions are legislating to classify this as a form of child labour.

6.6 Older adulthood

Ageing adults could look for different ways to achieve economic security. Retirement as we know it may become much less common. More people with fewer savings might have to delay their retirement. Others could engage in geoarbitrageFootnote117: lower-income countries are increasingly offering pensioners incentives to relocate—from “retiree” classes of citizenship to discounts on utility bills.Footnote118 Different decisions on pensions and savings could be made earlier in the life course. Demand could grow to address age discrimination in workplace recruitmentFootnote119 and accommodations.

Geoarbitrage involves moving to a place with a lower cost of living, while keeping the same level of income.

Pervasive ageismFootnote120 might decrease as older adults take up more space in society relative to other age groups. New choices are emerging for wealthy older adults to spend the “third act” of their lives. Retirement communities on university campuses across North America aim to provide new revenue streams for universities and “living labs” for researchers.Footnote121 We may see a more radical “politics of old age” that pushes for greater entitlements and more consideration for the needs of older adults. This could take the form of grassroots movements or “grey interest” political parties.

Home design and infrastructure development may evolve to cater for an ageing population. Cities today are largely built around the needs of working-age, able-bodied adults. People living healthier lives for longer will expect greater independence in older adulthood than previous generations. New houses and infrastructure could anticipate changing health needs across the life course. The largest proportion of people aged 65 plus in Canada live in rural areas and the suburbs.Footnote122 As a result, we could see rising demand for home-based services and on-demand public transportation. Municipalities could create new zoning bylaws to enable older adults to form housing cooperatives.

7.0 Conclusion

The life course is changing. Many people are going back to education as adults to learn new skills for a changing labour market. It is harder to buy a house, so many live longer with families or friends. Some have children later in life, and raise them while caring for ageing parents. Others have no children, and worry about who will care for them in their final years. Some hope to enjoy a long and healthy retirement. Others worry they will need to keep working to make ends meet. These changes to life courses are already under way. But many more transformations are likely to emerge in the coming decades, driven by significant shifts in society.

This report has laid out an initial framework for thinking about transformative changes to future lives. It identifies potential implications for policy professionals, service-providing community organizations, the private sector, and people living in Canada. It is the starting point for additional foresight work by Policy Horizons in this area. Future work will look at how forces of change interact with one another, operate within different contexts, and apply to different subpopulations whose life courses may face specific constraints and involve different options.

We look forward to collaborating with partners and stakeholders to develop policy-relevant foresight about future lives.

Acknowledgements

This report synthesizes the thinking, ideas, and analysis of many contributors through research, interviews, conversations, and workshops.

The project team would like to thank the experts who generously shared their time and expertise in support of the research: Faiz Abhuani, Kristopher Alexander, Suzanne Brant, Alana Cattapan, Robert Crampton, Jacquie Eales, Gillian Einstein, Janet Fast, Nicole Frenette, Ilana Gershon, Alison Gopnik, Deborah Hayek, Andy Hines, Brett Kubicek, Blair McMurren, Gail Mitchell, Christine Overall, Peter Padbury, Atiq Rahman, Patti Ranahan, Kathleen Rice, Jennifer Robson, Sahar Sadjadi, Nathan Svenson, C. Thi Nguyen, Amanda Watson, Donna Wilson, as well as those who wish to remain anonymous.

Project team

John Beasy, Foresight Analyst

Jennifer Lee, Foresight Analyst

Nicole Rigillo, Senior Foresight Analyst

Simon Robertson, Manager, Social Foresight

Tieja Thomas, Manager, Senior Foresight Analyst and Project Lead

Kristel Van der Elst, Director General

Communications

Maryam Alam, Communications Advisor

Laura Gauvreau, Manager, Communications

Géraldine Green, Communications Advisor

Alain Piquette, Graphic Designer

Andrew Wright, Writer (external)

Nadia Zwierzchowska, Senior Communications Advisor

We would like to thank our colleagues Imran Arshad, Marcus Ballinger, Fannie Bigras-Lafrance, Alexis Conrad, Kurt Richardson, and Claire Woodside for their support on this project.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2022

For information regarding reproduction rights: Contact Policy Horizons

PDF: PPH4-192/2022E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-43261-8